Erik Sass is covering the events of the war exactly 100 years after they happened. This is the 256th installment in the series.

NOVEMBER 7, 1916: WILSON WINS REELECTION

The 1916 U.S. presidential election saw the acceleration of a major political realignment, as the Democratic Party led by Woodrow Wilson sought to build a stable majority by co-opting many of the activist ideals previously espoused by the “Progressive” wing of the Republican party, while the latter struggled to heal the ideological fractures laid bare in the 1912 election.

In the end the GOP was unable to rebuild its coalition in the face of Wilson’s wily policy poaching, handing the election – and with it, the direction of U.S. foreign policy towards war-torn Europe—to the Democratic incumbent.

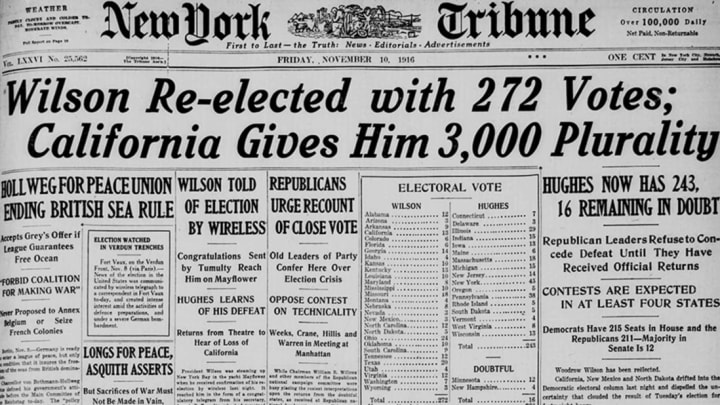

On November 7, 1916, after a hard fought campaign, Wilson squeaked out a win with 277 electoral votes to 254 for his Republican opponent Charles Evan Hughes, drawing on the Democratic Party's traditional Southern strongholds, as well as relatively new converts in the Mountain West and West Coast. The final decision hinged on one of the big swing states, California, with a modest 13 electoral votes (the full tally wasn’t known for almost a week afterwards, reflecting the technology of the era).

Erik Sass

PROGRESSIVE PIVOT

Of course the war itself was a major issue in the 1916 election, along with the punitive expedition against Pancho Villa, but these were just two controversies among many. Vast and inwards-looking by nature, the United States was also energized and divided by a range of domestic questions, which were at least as important to the outcome of the contest as the debates over American intervention in Europe and Mexico.

The arguments which most divided public opinion in these years generally concerned the social and economic impacts resulting from the country’s rapid industrialization over the preceding half-century, which had provided a new host of ills for the crusading Progressive movement to attack following the demise of slavery. Internal disagreements over these issues had contributed to the open split in the Republican Party in 1912, pitting the Progressive wing under Teddy Roosevelt, who supported organized labor and trust-busting, against the laissez-faire conservative wing under William Howard Taft.

In the unusual four-way presidential contest of 1912, between Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft, and the socialist Eugene Debs, this dissension in the Republican ranks ended up giving the White House to Wilson with just 41.8% of the popular vote. Stung by this largely self-inflicted defeat, in 1916 the GOP resolved to unite around a single compromise candidate who could win back Progressive voters. They eventually settled on Associate Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes, who resigned his position to run for office (and was later appointed Chief Justice of the Supreme Court by Herbert Hoover, making him one of only two justices in U.S. history to be appointed twice).

Facing a resurgent Republican coalition, Wilson decided to tack towards the center by adopting a slew of Progressive policies, including the formation of new agricultural banks to lend to farmers – a move which naturally appealed to Wilson’s Democratic base in the rural South, but also curried favor with Midwestern farmers previously more likely to vote Republican. A workmen’s compensation act for federal employees was also passed with relative ease, since it didn’t affect the private sector.

Other Progressive moves by Wilson required a careful balancing act to avoid alienating key members of the Democratic coalition: for example his decision to support a law banning child labor annoyed Democratic Senators from southern states with lots of textile factories, but in July 1916 they finally heeded the president’s call and passed the bill (probably swayed by the inducement of the agricultural banks).

Perhaps the clearest signal of this new direction was Wilson’s appointment, in January 1916, of the pro-union lawyer Louis Brandeis to the Supreme Court, a major victory for organized labor. Also shocking was Wilson’s support for trade tariffs and anti-dumping legislation to protect American industry from foreign competitors, reversing almost a century of Democratic support for free trade with the brazen theft of a plank from the Republicans’ 1912 platform.

"HE KEPT US OUT OF WAR"

The war undoubtedly played a role in the presidential contest of 1916, but it would be hard to argue that it was decisive, considering that key players on both sides were at pains to highlight their opposition to U.S. intervention, and both presidential candidates left their stances ambivalent at best, exemplified by Wilson’s famous slogan “He Kept Use Out of War” (with no guarantee he would continue to do so).

No surprise, these stances mirrored the state of American public opinion. On one hand, a vocal minority – exemplified by the bellicose former President Teddy Roosevelt—had favored U.S. intervention on the side of the Allies almost from the beginning, citing Germany’s violation of Belgian neutrality and the “outrages” (atrocities) committed by German troops in Belgium and northern France. Later some Americans were swayed to the pro-war side by the German submarine campaign against neutral shipping, including the sinking of the Lusitania, with the loss of scores of American lives.

Indeed, some Americans were so committed to the idea of intervention that the Preparedness Movement, as it was called, set up privately funded officer training programs to teach citizens military skills at so-called “Plattsburgh Camps,” named after the chief training facility in Plattsburgh, NY. Altogether around 40,000 young men, almost all drawn from the college-educated upper class, underwent training at these camps.

On the other hand, a majority of Americans continued to oppose U.S. intervention well into 1916, and what limited support for intervention there was tended to wane when Germany appeared to satisfy U.S. diplomatic demands by backing down from unrestricted U-boat warfare, as it did in 1915 and 1916. Meanwhile the British naval blockade of the Central Powers and blacklisting of companies that traded with them, which hurt American businesses, dampened pro-Allied sentiments considerably.

Always mindful of these attitudes, Wilson sought to placate the pro-intervention segment of public opinion by launching his own “Preparedness” drive, with new bills expanding the U.S. Army and Navy, and constant diplomatic pressure on both Germany and Britain to cease threatening American lives and interfering with American commerce on the high seas.

These measures allowed him to avert war while maintaining American prestige at home and abroad, which in turn enabled him to both preserve the loyalty of the Democratic Party’s staunch pacifist wing, led by William Jennings Bryan, and deprive his Republican opponents of political ammunition at the same time. In fact, Republican grandees nixed a possible run by Teddy Roosevelt in 1916 because they feared, probably rightly, that his open pro-war stance would cost them the election. During the campaign Republicans criticized Wilson for being too soft when it came to German submarine warfare, but hardly committed to armed intervention themselves.

Despite that Wilson’s reelection came as a disappointment to pro-Interventionists who viewed him as practicing what a later generation would call “appeasement.” Edmond Genet, an American volunteer fighting with the French air force as a pilot, was typically despondent in a letter home written November 15, 1916:

"Hughes lost and there’s another four years ahead of us with Wilson at the helm… we have lost every bit of hope… Where has all the old genuine honor and patriotism and human feelings of our countrymen gone? What are those people, who live on their farms in the West, safe from the chances of foreign invasion, made of, anyway? They decided the election of Mr. Wilson. Don’t they know anything about the invasion of Belgium, the submarine warfare against their own countrymen and all the other outrages which all neutral countries, headed by the United States should have long ago rose up and suppressed and which, because of the past administration’s “peace at any price” attitude have been left to increase and increase?"

DRIFTING TOWARDS WAR

But behind the scenes the U.S. was already drifting towards war as 1916 drew to an end, even if most ordinary Americans didn’t realize it. Abroad, the new military high command in Germany, led by chief of the general staff Paul von Hindenburg and his close collaborator Erich Ludendorff, was usurping the authority of the civilian government by pushing Kaiser Wilhelm II to resume unrestricted U-boat warfare, on the assumption that the United States either wouldn’t fight or would declare war in name only.

Even before the resumption of unrestricted U-boat warfare became known, Germany and the U.S. were on a collision course, due to individual submarine commanders overstepping their bounds, apparently with the winking acquiescence of Berlin. Thus on November 20, 1916, Wilson’s personal confidante Colonel E.M. House wrote to Secretary of State Robert Lansing, relating a conversation he had with the German ambassador, Bernstorff, in which House warned the German diplomat “we were on the ragged edge and brought to his mind the fact that no more notes could be exchanged: that the next move was to break diplomatic relations.” Across the Atlantic, in his memoirs the American ambassador to Germany James Gerard, recalled that sometime in the autumn of 1916 Ludendorff “had stated that he did not believe America could do more damage to Germany than she done if the two countries were actually at war, and that he considered that, practically, America and Germany were engaged in hostilities.”

Other, possibly more powerful forces were also pushing the U.S. towards war. Beginning in 1915 U.S. banks had loaned colossal sums to the Allies—with Wilson’s tacit permission—and the country was enjoying an economic boom as these loans were funneled back to U.S. manufacturers for weapons, ammunition, vehicles, food, fuel, and other supplies (giving rise to the U-boat controversy). As much as the Allies now depended on U.S. production to sustain their war effort, it was also becoming clear that American banks and industry were equally dependent on the Allies for their solvency.

Caught in a tightening vise formed by two interrelated pressures—the threat of renewed U-boat warfare and America’s growing entanglement with the Allies—Wilson was running out of room to maneuver.

See the previous installment or all entries.