Erik Sass is covering the events of the war exactly 100 years after they happened. This is the 251st installment in the series.

September 26-29, 1916: The Tide Turns Against Romania

At first glance the entry of Romania into the First World War on the side of the Allies looked like another disaster for the Central Powers, capping a year of disappointments and setbacks including Verdun, the Brusilov Offensive, and the Somme. With an army 800,000 strong – on paper, at least – and promises of help from the Allies, it seemed like Romania’s declaration of war against Austria-Hungary could be the final nail in the coffin, sealing the fate of the Habsburg realm and with it Germany’s hopes for victory.

This interval of Allied optimism proved short-lived, however. As the British, French and Russians soon discovered to their dismay, Romania only had enough weapons and equipment to field half a million troops, and its isolated position in Eastern Europe meant there was no way for the Allies to deliver supplies in the quantities necessary to make up the difference. Meanwhile by September 1916 the Russian Brusilov Offensive (whose stunning success over the summer helped convince Romania to join the Allies in the first place) had finally run out of steam, freeing up German and Austrian troops to fend off the Romanian offensive and then launch a counterattack.

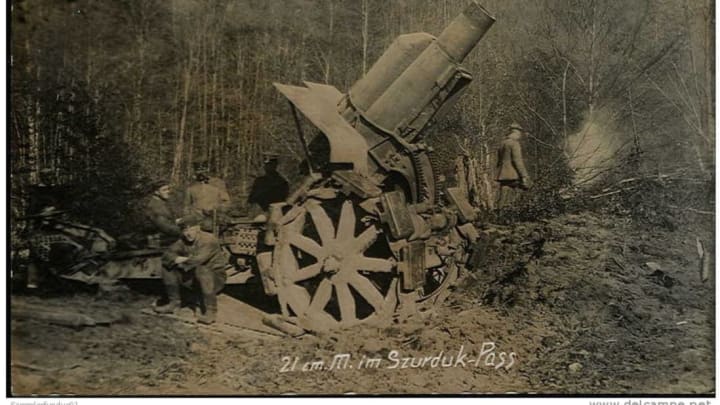

Click to enlarge

After crossing the Carpathian Mountains and briefly occupying Austria-Hungary’s Transylvanian borderlands in early September, the Romanian adventure came to a sudden, sobering end on September 16 with the arrival of Erich von Falkenhayn, until recently the German chief of the general staff, now the commander of the new hybrid Austro-German Ninth Army facing the Romanians in Transylvania. For Falkenhayn, cashiered from the top spot for the failure at Verdun, this field command was a chance to redeem himself in the eyes of the German Army and public – and he did so in spectacular fashion.

Assisting Falkenhayn was another near-legendary German commander, August von Mackensen, who took command of the German-Bulgarian Donauarmee or Danube Army along Romania’s southern border, further divided into eastern and western operational groups (including the Bulgarian Third Army in the east). Together Falkenhayn and Mackensen’s forces effectively encircled Romania, setting the stage for a crushing counteroffensive in the fall of 1916.

The first blow landed almost immediately, with Mackensen’s invasion of the disputed province of Dobruja between the lower Danube River and the Black Sea on September 3, 1916. In short order Mackensen’s hybrid German-Bulgarian forces captured the border town of Silistra, then pushed the unprepared Romanians back almost halfway to Constanta, Romania’s biggest port and a key supply hub. Although the hybrid Russo-Romanian Dobruja Army won a brief reprieve with their victory over the Bulgarian Third Army at the Battle of Cobadin from September 17-19, enforcing a temporary stalemate on the Danube front, they couldn’t prevent Mackensen from capturing the fortress of Turturkai on the Danube on September 26, along with 25,000 prisoners.

Battle of Hermannstadt

But all this was only a prelude to the debacle now unfolding to the northwest, where the Germans inflicted a shattering defeat on the Romanian First Army at the Battle of Hermannstadt from September 26-29, 1916.

The dominant natural feature in this area was the towering Carpathian Mountains, which ran south and west along the Hungarian and Romanian frontiers, forming a natural border between them. In the opening days of their offensive the Romanians had crossed the mountains through a handful of passes to capture the Hungarian borderlands – but this superficial success had dire consequences, as the advance through the passes channeled the Romanian armies away from each other, separated by the intervening mountain ranges. Strung out on the far side of the Carpathians, the Romanian armies were unable to coordinate mutual support, leaving them all exposed to flank attacks and encirclement.

Falkenhayn took advantage of these disjointed deployments to attack the Romanian armies and destroy them “in detail,” or one at a time, aided by Mackensen’s attacks in the south, which forced the Romanians to weaken their invasion force in Hungary. He first struck the Romanian First Army at Hermannstadt on September 26, in order to clear the enemy from the approaches to the key passes across the Carpathians, including the Turnu Roșu or Red Tower Pass south of Hermannstadt.

Falkenhayn’s Ninth Army included the famous Alpenkorps or Alpine Corps, composed of Prussian and Bavarian “hunters” or woodsmen who were used to mountain conditions and rough terrain. Taking advantage of their high mobility, Falkenhayn sent the Alpenkorps around the Romanian First Army to threaten its supply lines in the rear, while his main infantry force launched a frontal assault against it from the west.

As German artillery pounded the Romanians from the front, pinning them down the Alpenkorps crossed the Sibin Mountains (a branch of the Carpathians), slipped around the enemy force to the east and occupied the Red Tower Pass, severing Romanian communications across the Carpathians. Meanwhile Austro-German forces from the neighboring Austro-Hungarian First Army harried the Romanians even further east, making it impossible for the Romanian high command to send reinforcements to the First Army.

Panicked by the prospect of being cut off and destroyed, the Romanian First Army commander, Ioan Culcer, had no choice but to order a hasty withdrawal, abandoning Hermannstadt and with it the central position in Transylvania. By September 29 the Romanians were in full retreat towards the mountain passes – which they would have to fight to clear (along with forces transferred from other spots, weakening the Romanians along the whole front). One German junior officer recalled the scenes of carnage that followed:

The Romanians repeatedly tried to break out of the encirclement. Upon reaching the pass and finding it blocked, and being exhausted after the strenuous march over the difficult mountain paths, the Romanians were taken over and completely destroyed by the Alpen Corps attacking from their rear. The losses in the Romanian units were terrible. The Alpen Corps had placed a tight grip on the road to the pass. The Romanians repeatedly attempted a breakthrough. German rifles and machine guns reaped a bloody harvest. Those not killed or wounded fell back into the witches cauldron below. The panic which befell the swarming masses was indescribable. Horses, wagons, and artillery still in complete harness ran into the Alt river and disappeared into the depths of the water. Cows and herds of swine were jammed into the narrow pass roads intermingled with troops.

Worse, the defeat at Hermannstadt set in motion a chain reaction, as the Romanian Second Army had to move south to cover the First Army’s retreat, in order to avoid a collapse of the entire Romanian line. This was a portent of things to come.

For ordinary German soldiers, the march south to the Carpathians was both exhilarating and intimidating, as it took them through some of the most primitive terrain in Europe, including dark, towering forests. The same junior officer recalled the eerie experience of marching with his unit, by night, through the Transylvanian foothills towards the famed Vulcan Pass, fated to be the scene of a pivotal German victory in October:

A few minutes later the darkness of the forest had completely enveloped the soldiers. The smell of rot and mold was very strong. You could not see your hand in front of your face. They held on to the person in front either by his bayonet or webbing in order not to lose connection. The soldiers didn’t march on a defined mountain road, but a climbed a wildly overgrown mountain path which had been used by humans maybe once in ten years and then only by daylight…

See the previous installment or all entries.