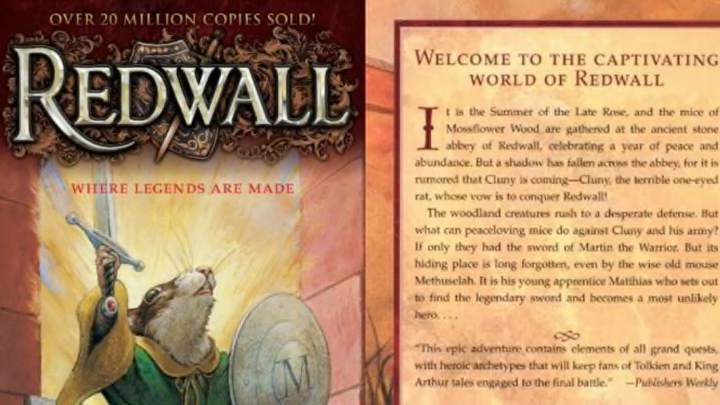

Jam-packed with characters and conflict from the shores of tumultuous Abbey Pond to the mountain fortress of Salamandastron (and filling 22 novels), the realm of Brian Jacques’ Redwall series was a huge place for both heroic woodland creatures and avid young readers alike—ultimately, one “as big or as small as you want it to be in your imagination,” Jacques once told Scholastic.

So whether you were forever aligned in heart and deed with the mores of Martin the Warrior or found yourself secretly cheering for the Feral Cat Army of Green Isle, there’re probably a few epic secrets about the books’ noble species, vermin, and creator that you never uncovered in your journeys around Redwall Abbey.

1. BRIAN JACQUES’ SURNAME IS PRONOUNCED “JAKES” (YES, REALLY).

Born James Brian Jacques in Liverpool, England in 1939, the prolific author’s last name is pronounced “jakes,” like “makes” or “takes,” as The New York Times and Washington Post pointed out in 2011 after Jacques passed away. And while the surname’s spelling seems to suggest French heritage somewhere along the way (and Jacques would often say his father was half-French), the family isn’t sure of its origin.

2. IN HIS YOUTH, JACQUES WORKED AS A MERCHANT MARINE, A POLICE CONSTABLE, A BOXER, AND MORE.

The renowned writer was “reared by the Liverpool docks,” according to the Times, and showed early promise at the age of 10 with “a fine short story about a bird and a crocodile.” Sadly, however, his teacher thought it was too good (to be written by a child, that is) and caned Jacques as punishment for the perceived plagiarism.

By the age of 15, Jacques had had his fill of school (and his father), and signed on for work as a merchant seaman—the first of various jobs he’d hold over the next few decades, which included work as a longshoreman, a boxer, a bus driver, a stand-up comic, and a “bobby,” or police constable.

3. HE GOT THE IDEA FOR REDWALL WHILE VOLUNTEERING WITH BLIND STUDENTS ...

In the years before Redwall, the series’ first book, was published in 1986, Jacques was working as a milkman in Liverpool and volunteering as a reader for students at the Royal School for the Blind, a regular stop on his route. According to The New York Times, however, he found the reading material to be “dreadful” and “preoccupied with the ‘here and now’ of teenage angst and divorce.” So he set out to create better children’s lit for these students—the proper kind, with heroes, villains, and the former’s adventurous triumph over the latter. He told the Times,

"I thought, 'What's wrong with a little bit of magic in their lives?' … So I went home and wrote on recycled paper. It took me seven months, each night. And it came to 800 pages because I just used one side. I had all of these pages in a supermarket bag.

4. ... AND GOT PUBLISHED AFTER A FRIEND SECRETLY SUBMITTED HIS MANUSCRIPT.

Jacques handed off this supermarket bag to Alan Durband, a friend and retired teacher, to get his thoughts on it. Durband sent the story off to several English publishers, landing Jacques a first contract for around $4000—an offer so modest that, according to the Times, Jacques “was so cautious about the future that he continued working as a stand-up comic while writing books” for the next four years.

5. MANY ANIMAL CHARACTERS ARE BASED ON PEOPLE JACQUES KNEW ...

Various characters in the long series are direct tributes to people in Jacques' life. A self-described “people watcher,” Jacques told Scholastic that nearly all his characters are “people or amalgamations of people [he] met in [his] life,” while many of their adventures are based on real-life encounters of him and his friends, too.

For example, his grandmother inspired the character of Constance, the badger guardian of Redwall, while Mariel the mousemaid is based on Jacques’ oldest granddaughter. Some whole species are based on real-life groups of people, too; as the Chicago Tribune reported, the hares in Jacques' books make reference to World War II bomber pilots, the shrews echo the dockworkers that Jacques lived among throughout his life, and his heavily accented moles take cues from “the ‘very old men’ in the villages of Somerset.”

6. ... BUT THE STORY’S MAIN HEROES REPRESENT BRAVE KIDS EVERYWHERE.

Jacques' experiences being a very frightened kid during the last years of WWII helped him bring some of the mice’s most terrifying and triumphant moments to the page. "My stories are written from the viewpoint of a kid, sitting in the movie house while World War II is on, watching all this magic come on the screen,” he told The New York Times.

To set the stage properly, Jacques worked to create what he called “interesting baddies” among the vermin and villains of Redwall Abbey and Mossflower Woods—ones that evoked the same fear he felt during childhood while watching the newsreels of the devastation of the war. But when it came time to pick the heroes, his choice was an easy one: “I like mice!" he told Scholastic. "Mice are my heroes because, like children, mice are little and have to learn to be courageous and use their wits.” With regard to the fierce clashes between heroes and villains in his stories, Jacques told the Times:

"My values are not based on violence. My values are based on courage, which you see time and time again in my books. A warrior isn't somebody like Bruce Willis or Arnold Schwarzenegger. A warrior can be any age. A warrior is a person people look up to."

7. GONFF THE MOUSETHIEF, ON THE OTHER HAND, IS JACQUES HIMSELF.

Jacques has frequently gone on the record about identifying closely with the lock-picking Gonff, who called both friends and enemies "matey." "Again I go back to me childhood," he told the Times. "He was a ducker and weaver, and so was I. There was nothing around, but if you came from a poor family and there was something left around, you picked it up. I came from the docks. Gonff tried to help others."

8. MANY BOOKS WERE WRITTEN UNDER AN APPLE TREE IN A REAL-LIFE PASTORAL HAVEN LIKE REDWALL.

Jacques mentioned in a Redwall teacher’s guide that his favorite place to write was “a corner of [his] garden, up near the angle of the wall,” where he’d settle in a little hut that he built for his granddaughter, preferably in the spring. When rain hit, he’d simply “go back under the lilac bush.”

9. REDWALL WAS ADAPTED INTO A TV SHOW AND A RADIO PLAY …

During Jacques’ life, the series was responsible for over 20 million books sold and was translated into 29 languages, but fans still couldn’t get enough. So, among other things, Redwall and two other books were adapted into a three-season animated series that aired between 1999 and 2001, while Jacques himself (along with his son, Marc, and a number of British voice actors) recorded a three-part audiobook called The Redwall Radio Play for fans’ enjoyment.

10. ... AND EVEN AN OPERA (A GENRE THAT JACQUES ADORED).

In 1998, Opera Delaware staged Evelyn Swensson’s Redwall: The Legend of Redwall Abbey, a two-act musical based on the series’ first book and which later toured for European audiences. It’s perhaps no surprise that Redwall was able to make waves in operatic form given that Jacques, a lifelong opera fan, spent years hosting a radio program called “Jakestown” on BBC Radio’s Merseyside station, and which featured many of his all-time favorite pieces and voices.

11. THERE’S A REDWALL-INSPIRED COOKBOOK.

The Redwall Cookbook offers recipes for many of the sumptuously described dishes in the series, including Mole's Favourite Deeper'n'Ever Turnip'n'Tater'n'Beetroot Pie, Applesnow, and Crispy Cheese'n'Onion Hogbake. Written by Jacques himself, the book is divided into the four seasons and also features small tidbits about Redwall's characters.

12. STILL WANT MORE REDWALL? YOU CAN PLAY TWO TEXT-BASED GAMES ONLINE.

Jacques passed away in 2011, but thanks to his many legions of fans, the universe he created is still going strong. Two text-based online games still offer access to role-playing and chat with other Redwall fans: Redwall: Warlords and the Redwall MUCK (or Multi-User Chat/Created/Computer Kingdom).