The First World War was an unprecedented catastrophe that shaped our modern world. Erik Sass is covering the events of the war exactly 100 years after they happened. This is the 219th installment in the series.

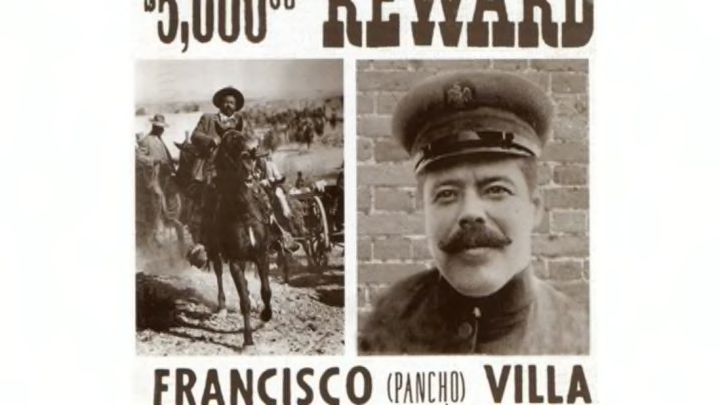

January 11, 1916: Pancho Villa’s Troops Murder 18 Americans

On January 11, 1916, a group of bandits associated with the Mexican guerrilla leader Pancho Villa stopped a train at Santa Ysabel in Chihuahua state, forced nineteen mining engineers from the American Smelting and Refining Company to get off, and then shot them all, with just one man surviving by playing dead. The sole survivor, Thomas B. Holmes, recalled:

Just after alighting, I heard a volley of rifle shots from a point on the other side of the cut and just above the train. Looking around, I could see a bunch of about 12 or 15 men standing in a solid line, shoulder to shoulder, shooting directly at us… Watson kept running, and they were still shooting at him when I turned and ran down grade, where I fell in some brush… I saw that they were not shooting at me, and thinking they believed me already dead, I took a chance and crawled into some thicker bushes. I crawled through the bushes until I reached the bank of the stream… There I lay under the bank for half an hour and heard shots by ones, twos and threes.

A Mexican miner who was present told a correspondent for the New York Sun:

No sooner had the train been brought to a standstill by the wreck the bandits had caused than they began to board the coaches. They swarmed into our car, poked Mausers into our sides, and told us to throw up our hands or they would kill us. Then Col. Pablo Lopez, in charge of the looting in our car, said: “If you want to see some fun watch us kill these gringoes. Come on, boys!” he shouted to his followers… I heard a volley of rifle shots and looked out the window… Colonel Lopez ordered the “tiro de gracia” given to those who were still alive, and the soldiers placed the ends of their rifles at their victims’ heads and fired, putting the wounded out of misery.

This outrage was the latest chapter in Villa’s long, twisted relationship with the United States, which had actually supported the charismatic rebel leader for a time.

After the liberal reformist president Francisco Madero was overthrown by Victoriano Huerta in 1913, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson turned against the brutal military dictator and offered support to a challenger, Venustiano Carranza, who ousted Huerta the following year with support from Villa and another rebel leader, Emiliano Zapata. Carranza, who did not want to be seen as an American puppet, rebuffed Wilson’s offer of help, and further alienated him with nationalistic policies which threatened U.S. business interests, as well as his illiberal attacks on the Catholic Church in Mexico. Meanwhile Villa and Zapata had both turned on Carranza as well, and in 1914-1915 the U.S. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan sided with Villa, whom he believed was committed to democratic ideals. Villa, a savvy publicist, also curried favor with U.S. public opinion by striking deals with American film companies, and even recruited Americans to join his army (below).

However, after Carranza’s forces inflicted serious defeats on Villa’s rebel army in April 1915 Bryan gave him up as a lost cause, and towards the end of the year Wilson – faced with a fait accompli – reluctantly threw in his lot with Carranza, who promised democratic reforms and an end to religious persecution.

Villa viewed this shift as a betrayal by the U.S. government, and began pursuing a new strategy: instead of trying to overthrow Carranza directly, he would provoke a war between the U.S. and Mexico that would result in U.S. intervention and the collapse of Carranza’s regime.

Villa hoped to provoke war by raiding the U.S. border, killing American citizens and destroying property in order to inflame public opinion. And this approach worked remarkably well: after the massacre of the American mining engineers in Santa Ysabel, El Paso, Texas, was placed under martial law to prevent its enraged citizens from organizing a militia and carrying out reprisals in neighboring Ciudad Juarez, Mexico.

New York Tribune via Chronicling America

Despite calls for military action by the Senate, Wilson refused to declare war over an atrocity committed by bandits, and instead called on Carranza to apprehend Villa and his men. This was a tall order, as Villa’s force of around 1,500 troops was running free in the vast, remote reaches of northern Mexico, and the guerrilla leader remained determined to precipitate a conflict between the two national governments.

After committing several further atrocities, Villa almost succeeded in this aim – and the tense situation he helped create laid the groundwork for the infamous Zimmerman Telegram scandal, in which Germany secretly tried to stir up war between the U.S. and Mexico in order to distract the U.S. and prevent it from joining the war in Europe.

See the previous installment or all entries.