In 2015, we often use the term “tarred and feathered” to describe crowd-sourced vendettas against strangers (like ganging up on someone through social media) or retaliation from one’s peers. What your typical angry mob might not know is that tarring and feathering didn’t actually use tar as we know it; that removing the stuff could be extremely tough (and very painful); and how the centuries-old punishment sticks around today.

RICHARD THE LIONHEART FEATHERS SEA BURGLARS

In the U.S., we often associate tarring and feathering with mob justice in the Old West. In the 1971 cartoon Lucky Luke: Daisy Town, narrator Rich Little (impersonating James Stewart) even gives simple, step-by-step instructions for turning a frontier hooligan into what he calls a “Western souffle” using tar and feathers. However, the practice actually began far earlier in Europe, and was first documented in an 1189 proclamation from Richard the Lionheart for punishing any thieves discovered on his crusading sea vessels:

[He] shall be first shaved, then boiling pitch shall be poured upon his head, and a cushion of feathers shook over it so that he may be publicly known; and at the first land where the ships put in he shall be cast on shore.

TAR, PINE TAR, AND PITCH (OH, MY)

If you’re envisioning miscreants being slathered with bubbling roofing tar, think again. Unlike the petroleum-based tar that we now use for paving roads, the sticky stuff used for tarring and feathering unlucky truants for hundreds of years has usually been either pine tar (derived from the wood of pine trees, as the name suggests) or pitch, which traditionally was the name for resin and only later got attached to petroleum products.

Wood tar was first used for waterproofing wooden ships and structures in ancient Greece, and Northern Europeans began refining birch bark in the Neolithic. Using either destructive or dry distillation to drain the natural tar and pitch from wood or peat piles by harnessing heat, time, and/or simple gravity, they helped make tar a major industry—one that later earned North Carolinians the nickname “Tar Heels” because of their tar-rich pine forests.

For the most part, artificial sealants replaced natural wood tar and pitch in the 20th century, but petroleum sealants are very tough viscoelastic polymers in their own right and take a long time to change shape. The Pitch Drop Experiment, the Guinness World Records’ longest-running lab experiment, has been tracking a cone of unheated pitch as it’s been slowly forming and releasing droplets since 1930—over 85 years later, that batch of pitch is only working on its tenth drop. While pine tar and pitch have lower melting points than petroleum tar, being painted with their melted forms could still be very painful, leading to blistering burns and stripping the skin off when it came time to peel the tar away.

TAR GOES GLOBAL

Centuries after Richard ordered the punishment for oceangoing robbers, it was being used throughout Europe for social indiscretions. Historian Benjamin H. Irvin points out, for example, that “the Bishop of Halverstade ordered that tar-and-feathers be applied to a party of drunken friars and nuns” in 1623. Because tar and pitch were often in great supply around shipyards and on sea vessels, the naval boom of the last millennium’s middle brought the practice around the world, too: Irving found that, “in Dominica in 1789, a British soldier caught committing bestiality with a turkey was drummed out of his regiment while forced to wear the bird's feathers ‘round his neck [and] on his beard.’”

JOSEPH SMITH'S BRUSH WITH FEATHERS

Americans got in on the act as well. Joseph Smith, founder of the Mormon religion, endured his own tar and feather attack in 1832, possibly after an aborted attempt to castrate him—the result, according to different accounts, of community animosity over either his sexual activity, his attempts to take away community property, or a combination thereof. Smith remembered,

I found myself going out of the door, in the hands of about a dozen men [...] They ran back and fetched the bucket of tar, when one exclaimed, with an oath, ‘Let us tar up his mouth;’ and they tried to force the tar-paddle into my mouth [...] All my clothes were torn off me except my shirt collar; and one man fell on me and scratched my body with his nails like a mad cat [...when afterward] I came to the door I was naked, and the tar made me look as if I were covered with blood, and when my wife saw me she thought I was all crushed to pieces, and fainted [...] My friends spent the night in scraping and removing the tar, and washing and cleansing my body; so that by morning I was ready to be clothed again.

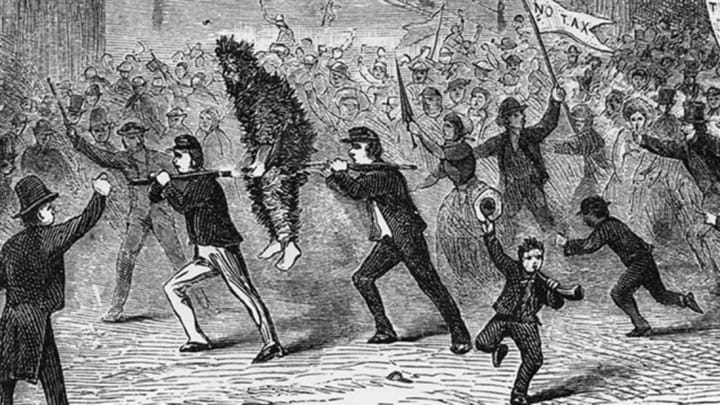

Tarring and feathering also became a form of political retaliation for the poorer classes a few centuries ago. In 1696, Irving said, “an angry crowd imposed [the] punishment upon a London bailiff who attempted to arrest a debtor,” while patriots in colonial New England seaports used it from the 1760s to oust customs officials and British loyalists (or “make macarony”) and other traitors to their cause, like those who squealed on patriot smuggling operations (giving them the “informer’s uniform”).

By the 19th century, the practice had spread well inland in the U.S., and was wielded by small towners of both genders, who often improvised with easier-to-find materials like syrup and cattails when official justice was absent or unsatisfactory.

Modern Takes on an Antiquated Punishment

Patriotic Americans might not mourn a few Brits getting feathered 300 years ago, but the technique sadly didn’t fall off as a popular form of U.S. mob "justice" even when the 20th century rolled around. Starting in antebellum days and continuing beyond the civil rights era, many African Americans and civil rights activists were tarred and feathered.

Tarring and feathering also saw a European resurgence during “The Troubles” in Northern Ireland, in which the punishment was again wielded to weed out perceived “traitors.” As in a 1971 case involving a teenage girl, some nationalist supporters used the method to discourage and humiliate young women and some other community members thought to have fraternized with occupying British soldiers. Tar and feathering has persevered into the 21st century in the area. In 2007, a Belfast man was trussed by two others, thought to be UDA members, for allegedly dealing drugs in the community.

The occasional case of responding to supposed sexual impropriety with tar and feathers has cropped up in recent decades in the U.S., too. In 1981, an Alabama woman was tried on various charges for the tarring and feathering of her ex-husband’s then-fiancee using a tar-like substance meant for home weatherproofing—an act which she defended as necessary in taking a stand for “a sense of community decency” against the couple’s wedding plans. While her act may have had a long historical precedent, she was still convicted.