Frank and Joe Hardy have been blowing mysteries wide open for almost 90 years, combating ghosts, thieves, monsters, and shifty characters to the delight of several generations of kids. Fans of The Hardy Boys books might have caught a lot of the action along the way, but they may not realize that the series is its own shady case file that involves changing American tastes, furious librarians, and the shadowy, corrupt business of kids’ books.

1. THE BOYS HAVE SOLVED AROUND 500 CASES.

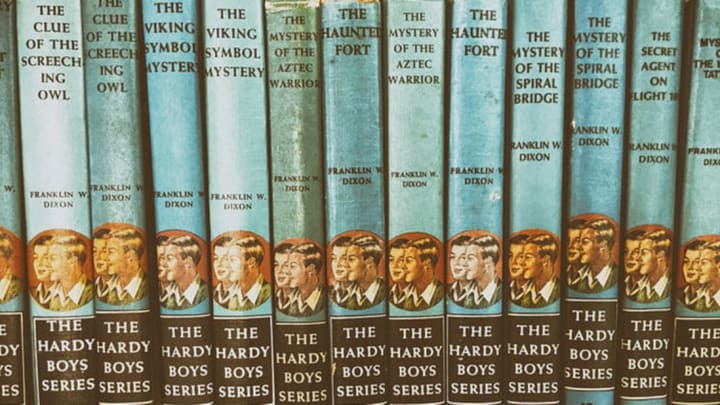

Not including graphic novels and planned releases, there have been well over 450 Hardy Boys titles published since their 1927 debut. This rough sum includes 38 titles from the original series that were entirely rewritten after 1959, releases by Grossett & Dunlap and digests from Simon & Schuster publishers, and the spinoff Clues Brothers, Undercover Brothers, Casefiles, Super Mysteries, and Adventures series, among others.

2. THE BOOKS LET KIDS ENJOY ADULT ENTERTAINMENT.

Around the beginning of the 20th century, Edward Stratemeyer, who The New York Times called “a prolific hack with a nose for business” and “the Henry Ford of children's fiction,” had a revelation that would change children’s literature forever. Stratemeyer saw that, while most kids’ lit to date focused on moral instruction, kids themselves wanted to experience the same thrills their parents were getting from cheap series books that sold for a nickel to 10 cents a pop. When he started publishing books that delivered this excitement, he realized that children would become attached to certain authors, so it was better for them to be written using a pseudonym that he owned, than by an individual author who could leave. Thus, the high-output children’s series market was born.

3. THEY ARE ALL GHOST-WRITTEN.

In the decades that followed, the Stratemeyer Syndicate employed a changing stable of ghostwriters to churn out Hardy Boys titles (under the shared pseudonym Franklin W. Dixon) in as little as three weeks. These writers also filled the pages of Nancy Drew, Bobbsey Twins, Bomba the Jungle Boy, and Tom Swift books at breakneck speed, usually for a flat per-book fee of between $75 and $125 with no royalties involved.

4. STRATEMEYER NAILED THE FORMULA.

This group of ghost writers enabled Stratemeyer to build his literary empire, and while he sometimes provided bare bones storylines for his writers to work from, his instructions to Hardy Boys writers, the Times notes, “were basic: end each chapter with a cliffhanger, and no murder, guns, or sex.”

5. IN THE BEGINNING, THOUGH, THEY WERE SHREWD ANTI-AUTHORITARIANS ...

Like many fiction and comic titles of the era, The Hardy Boys books coming out in the late 1920s and ‘30s showed a gritty, no-nonsense world (or the kids' version of it) where Frank, Joe, and their pals functioned as fearless private eyes, taking the pursuit of justice into their own hands because of authority’s impotence. Bumbling policemen often interfered with their investigations and even briefly jailed them as stuffy retribution for the boys’ ingenious work. In the second-ever Hardy Boys book, The House on the Cliff, Frank finds it necessary to put pressure on the local police chief in order to further real justice:

‘Of course, chief,’ said Frank smoothly, ‘if you're afraid to go up to the Polucca place just because it's supposed to be haunted, don't bother. We can tell the newspapers that we believe our father has met with foul play and that you won't bother to look into the matter [...]’ ‘What's that about the newspapers?' demanded the chief, getting up from his chair so suddenly that he upset the checkerboard [...] ‘Don't let this get into the papers.’ The chief was constantly afraid of publicity unless it was of the most favorable nature.

6. ... ALL THANKS TO ONE VERY PROLIFIC CANADIAN GHOSTWRITER.

Leslie McFarlane wrote 19 of the first 25 Hardy Boys books and, according to many, singlehandedly defined the kind of detailed, moody prose for which the original series is lauded. In his version of Bayport, the simultaneous kid-friendly hamlet/atrocious hotbed of crime the boys call home, the Hardy family isn’t as wealthy as other Syndicate heroes, the boys happily accept monetary rewards, and the town’s rich folk come across as daft and greedy.

McFarlane clearly didn’t care much for the power structures in early 20th century U.S. culture, cops included. He wrote in his autobiography, Ghost of the Hardy Boys, "I had my own thoughts about teaching youngsters that obedience to authority is somehow sacred [...] Would civilization crumble if kids got the notion that the people who ran the world were sometimes stupid, occasionally wrong and even corrupt at times?”

7. WHILE MCFARLANE DIDN’T LOVE THE STATUS QUO, HE DID LOVE FOOD.

As the Times reflected, McFarlane “breathed originality into the Stratemeyer plots, loading on playful detail” that enthralled a young reader. He paid particular attention to his descriptions of meals, and to the sumptuousness of food from a young boy’s perspective. At the end of 1927’s The Tower Treasure, he included the following bacchanalian scene:

''For more than half an hour, they indulged in roast chicken, crisp and brown, huge helpings of fluffy mashed potatoes, pickles, vegetable and salads, pies and puddings to suit every taste, and when the last boy sank back in his chair with a happy sigh there was still food to spare.''

8. BY 1959, THE SYNDICATE NEEDED TO CLEAN UP THE HARDY BOYS’ ACT.

As a result of the 1953 United States Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, many publishers of children’s media worked hard throughout the '50s to get their stories in line with new legal and social standards for kid-appropriate material. Like other Stratemeyer Syndicate series, Hardy Boys books had often contained negative racial and gender stereotyping among its supporting and minor characters, many of which would shock modern audiences, but which were also considered unpalatable by readers in 1959.

9. BECAUSE OF THIS, IT SCRUBBED THE ORIGINAL RUN OF BOOKS.

That year, the Syndicate started rewriting 38 of its original Hardy Boys titles to remove objectionable material, including many of the books’ most violent moments. Writers also tried to give the books a more modern feel with fewer tough words, streamlined action plots, and generally updated language. Fans of the original series found the new bowdlerized versions to be downright bland, but Salon explained that some of the changes were reasonable:

“Dropped from The Missing Chums is ‘“I’ll say,’ replied Lola slangily,” as is ‘“So!’ she ejaculated, as the boys appeared.” Chet Morton’s car is referred to in The Tower Treasure as a ‘gay-looking speed-wagon.’ In the revision, the car loses this description but gains a name, ‘The Queen.’ (In this case there appears to be a wit at work, making the change something less than a total loss for literature.)”

10. IN THE 60S AND 70S, THE BOYS’ POLITICS ALSO CHANGED.

Starting in 1959 and carrying on through today, the boys have seemingly done a 180 regarding their distaste for authority (and, some critics argue, indeed now work to defend The Man). In 1969’s The Arctic Patrol Mystery, for example, Frank appears to have evolved into the kind of conscientious young American that much media of the day promoted:

“‘Great, Dad!’ Frank said, jumping to his feet. ‘With spring vacation coming up we won't miss any time at school!’

‘Are your passports up to date?’ his father asked.

‘Sure, we always keep them that way.’”

11. CLEANED UP OR NOT, LIBRARIANS HAVE ALWAYS HATED THEM .

Since the first Hardy Boys books were published, grown-ups have had trouble understanding their appeal—not just because the books contained violence and racial stereotypes, but because they were seen as literary garbage.

Even after the big cleanup in 1959, librarians continued to take issue with Syndicate works. "In our library traditionally we have never had this kind of mediocre book. Two-to-one my librarians [want to] uphold the superior selections we have," explained Virginia Tashjian, Chief Librarian for Newton, MA, to The Hour in 1978. The Spokane Daily Chronicle also noted in 1980 that the library banned Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys titles "because they 'lacked literary merit'” but still “retained Braille editions of Playboy magazine."

12. NEVERTHELESS, STRATEMEYER WAS DOING SOMETHING RIGHT.

In 1926 and 1927, the American Library Association surveyed kids in 34 U.S. cities, found that 'series books' were being read by 98% of respondents, and that "the books of one series [presumably the Bobbsey Twins] were unanimously rated trashy by our expert librarians [but] almost unanimously liked by the 900 children who read them."

13. KIDS ARE STILL INTO THEM.

Many of the Stratemeyer Syndicate's records are incomplete or lost, but estimates suggest that by 1975 Nancy Drew book sales had topped 60 million, Hardy Boys sales were over 50 million, and the Bobbsey Twins had hit 30 million. Since then, the Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys series have been steadily selling around one to two million copies per year (including many older titles), putting Hardy Boys all-time sales at over 70 million.

14. IN 2005, THE BOYS BECAME SECRET AGENTS FOR THE GOVERNMENT.

Since the introduction of the Undercover Brothers series, Frank and Joe have been top agents for American Teens Against Crime (ATAC), a secret government agency co-founded by their father to utilize kid agents when grown-ups won’t do. The agency delivers its orders via special CD-ROM that can only be played for instructions once. After the initial listen, it plays music like any other CD.

15. CRITICS STILL CAN’T QUITE EXPLAIN THE BOYS' POPULARITY.

No one can deny that The Hardy Boys series has stuck around due to popular demand, but decades later, critics still aren’t quite sure why. One idea is that the books are just fantastical, gripping, and vague enough to be relatable to any young reader. As a writer for Salon explained:

“Happily, the Hardy Boys series was unconcerned with reality [and the] boys’ characters basically broke down this way—Frank had dark hair; Joe was blond. [...] Generally, Frank was the thinker while Joe was more impulsive, and perhaps a little more athletic. I was blond, like Joe, and younger, like Joe. I liked Joe best. Franklin W. Dixon played me like a violin.”