The First World War was an unprecedented catastrophe that shaped our modern world. Erik Sass is covering the events of the war exactly 100 years after they happened. This is the 191st installment in the series.

July 9, 1915: Germans Surrender in SW Africa

With a few thousand German defenders massively outnumbered by the South African invasion force, there was never any doubt about the final outcome of the war in German Southwest Africa (today Namibia); the only question was how the endgame would unfold. As it turned out, the death throes of the German colony were surprisingly quick and painless, at least by the standards of the First World War, with a handful of casualties before capitulation.

After suppressing a short-lived Boer uprising in December 1914, South African Prime Minister Louis Botha led a multi-pronged invasion of Southwest Africa, including landings at the ports of Swakopmund (above) and Lüderitzbucht and incursions by cavalry converging from the South African interior on the southern city of Keetmanshoop. On March 20, 1915 Botha’s force sallied from Swakopmund to defeat the Germans at the Battle of Riet, clearing the way for an advance on the capital, Windhoek, which fell to the invaders on May 12, 1915. Henry Walker, a medical officer with the South African army, recalled the almost supernatural landscapes encountered during the advance in spring 1915:

It is quite impossible to do justice to the beauty of the country we passed through this night. The road and river were winding up a narrow gorge, frequently crossing each other. Giant acacias fringed the snow-white bed of the river, and extended to the greensward beyond. White rocks shone like silver in the river or on the mountain-sides, which towered high above everything… All this, illuminated by a most brilliant moon, has left an indelible impression on my memory.

The fall of Windhoek meant it was only a matter of time – but no one was sure how just how much time that meant. Would the German commander, Victor Franke, disperse his forces to continue the struggle with guerrilla tactics? Or might he try to retreat north into Portuguese West Africa (today Angola), or even head east and try to stir up tribal rebellions in British Rhodesia?

Actually Franke intended to make a last stand outside the northern town of Tsumeb, taking advantage of strong defensive positions in the hills around the town. To give his troops enough time to build fortifications, Franke sent a smaller detachment of around 1,000 men under of his subordinates, Major Hermann Ritter, to fight a holding action against the approaching South Africans under Botha. Ritter decided to fight the South Africans at Otavi, about 20 miles southwest of Tsumeb.

Botha, determined not to allow the Germans to dig in, drove his troops hard and covered a distance of 120 miles in less than a week, moving north along the main rail line – a remarkable achievement, considering the conditions and lack of supplies. One observer, Eric Moore Ritchie, recalled the final approach in the last week of June:

The pace of the trekking was now becoming phenomenal, and though the country was quite good, water was as scarce as ever, the bush being intensely dense, with thick sweet grass as much as eight feet high in places… During this trek the army had had water only twice… delay of any kind was now highly undesirable: the columns could not afford to pause long owing to the consumption of rations… water was uncertain, and congestion of columns at the watering places had to be avoided as much as possible.

Following this swift advance, on July 1, 1915 Botha managed to take the German rear guard under Ritter by surprise at the Battle of Otavi, pitting around 3,500 South African cavalry against 1,000 Germans – an encounter that would barely qualify as a skirmish on the Western Front. The Germans were overextended and had also failed to prepare fortified positions on the high ground behind them; thus when the German left flank began to crumble, the retreat quickly turned into a rout, leaving three German and four British soldiers dead.

As Ritter withdrew north, Botha divided his army of 13,000 cavalry and infantry into two wings, forming two arms of a pincer that encircled Franke’s smaller force of less than 3,000 men at Tsumeb over the following week. Franke’s troops, still digging in, suddenly found themselves surrounded and cut off from their only plausible line of retreat to nearby Grootfontein.

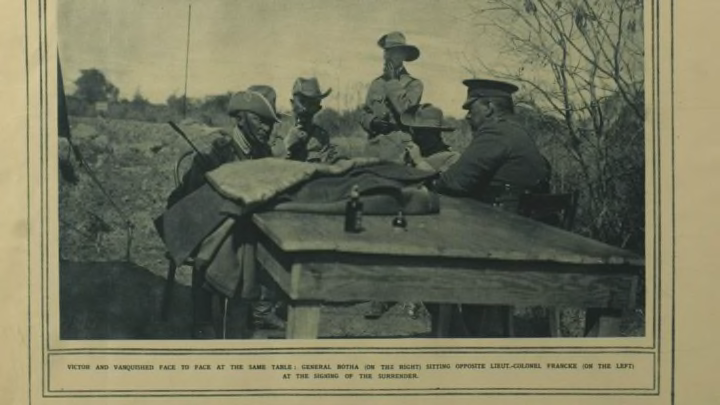

Facing overwhelming numbers with incomplete defensive works, Franke convinced the colony’s civilian governor, Theodor Seitz, to throw in the towel. The Germans surrendered to Botha on July 9, 1915 at Tsumeb (top, the surrender). Total casualties for the war in German Southwest Africa were 113 South Africans killed in battle, versus 103 Germans – a rounding error by the standards of the European war.

Having secured this victory the South Africans could now examine their conquests, prompting some to wonder whether it was all worth the effort. On returning to Lüderitzbucht, Walker summed up his impressions of the tiny harbor town (below, the town’s main street):

I don’t suppose there is a more desolate, dreary, God-forsaken site for a town in the whole world than this, and nobody except extreme optimists like the Germans would ever have dreamed of trying to establish one here. There is not a drop of fresh water anywhere near, nor a plant nor tree of any description except seaweed. There is not even a flat space where buildings can be erected, and many are perched on pinnacles or in fissures in the rocks. Its only natural advantages are the sun, sea, rocks, sand, and wind.

Whatever the land’s actual value, Botha fully intended for South Africa to profit territorially by its assistance to Britain in the Great War, and on July 15 the South African parliament voted to annex Southwest Africa in a customs union. South African domination of Namibia would continue after the Second World War, in defiance of United Nations resolutions, leading to the Namibian War of Independence from 1966-1988. This was followed by South African recognition of Namibian independence in 1990, as South Africa’s own apartheid regime began to collapse.

Battle in a Tornado

Meanwhile the Allies were also advancing in German Kamerun (today Cameroon), another vast but sparsely inhabited African colony located near the equator. The campaign in Cameroon was doubtless slow going as British, French, and Belgian colonial troops contended with rough terrain, thick tropical forests, and primitive infrastructure, but by July 1915 the (again, vastly outnumbered) German colonial forces had mostly retreated to the central plateau dominating the territory’s mountainous interior (below, British forces fire a field gun at the Battle of Fort Dschang, January 2, 1915).

On a map the Allies had Cameroon more or less surrounded, but this was hardly going to translate into an easy victory, as huge areas of mostly empty jungle allowed small guerrilla bands to slip in and out of contested areas at will. Thus as in German East Africa the Allies often found themselves fighting for possession of the same territory twice, or more: on January 5, 1915 they fought off a German counterattack at Edea, first conquered in October, and on July 22 they had to defend Bertoua, scene of a previous victory in December.

Nonetheless the Allies kept up the pressure and their native troops fought bravely in a number of actions. On April 29 they beat back a daring German incursion into Allied territory at Gurin in British Nigeria, then defeated the Germans again at the Second Battle of Garua from May 31 to June 10, 1915 (below, German native troops at Garua), completing the conquest of northern Cameroon (aside from the ongoing siege of Mora, where a small German force was now completely cut off on an almost impregnable mountain).

A small but dramatic encounter took place a few weeks later, when a British force attacked German defenders at Ngaundere on July 29 – in a tornado. The severe, indeed terrifying, weather conditions served to distract the small German garrison holding the village, allowing the British force of around 200 native troops to take them by surprise and capture many of them without a fight. As the storm cleared the remaining Germans launched a counterattack but were defeated, clearing the way for the British to advance to Tingere, repulsing a German counterattack from July 19-23, 1915. The arrival of the rainy season forced the end to campaigning for the middle of the year, although the siege of Mora dragged don to the north.

Allies Plan New Offensive

Back in Europe the Western Allies were planning a fresh offensive that would prove to be yet another costly disaster. On July 7, 1915 the first inter-allied military conference met at Chantilly, France, bringing together the French chief of the general staff Joseph Joffre, War Minister Alexandre Millerand, British chief of the general staff William Robertson, commander of the British Expeditionary Force Sir John French, and others to plot overall strategy.

Despite some initial resistance from the British, aghast at the huge cost of recent offensives at Neuve Chapelle, Aubers Ridge, and Festubert, French, Robertson and Secretary of State for War Lord Kitchener ultimately gave in to Joffre’s determination to keep up the pressure on the Germans. As Kitchener told French: “We must do our utmost to help the French, even though by so doing, we suffer very heavy losses indeed.”

After all, Joffre argued, the French had sustained far more casualties than the British, while the Western Allies needed to do everything they could to take some of the burden off the Russians, still reeling backwards in the Great Retreat. Additionally, the French war effort would be greatly increased by liberation of northern France, which held most of France’s factories and coal mines. Reflecting pre-war beliefs about the importance of “spirit,” Joffre also warned that if they stopped attacking, “our troops will little by little lose their physical and moral qualities.”

Although plans were vague, it was clear that a new coordinated Anglo-French offensive was intended for sometime in the late summer or fall, after the Allies had a chance to stockpile artillery shells for a massive opening bombardment. The plan that coalesced over the following months called for two simultaneous attacks, forming a huge pincer to cut off the German salient in northern France. In the south the French Second and Fourth Armies would attack the German Third Army, in what became known as the Second Battle of Champagne. Meanwhile to the west the British First Army would mount a huge push (using chlorine gas) with help from the French Tenth Army in the Third Battle of Artois – seared into British memory as the Battle of Loos.

See the previous installment or all entries.