There were seven of them—six Bosnian Serbs and one Bosnian Muslim—blending in with the crowds along Appel Quay, the promenade tracing the sluggish River Miljacka through downtown Sarajevo. Some were armed with pistols, some with grenades, each hoping to strike a blow against Austria-Hungary’s control of Bosnia on the sunny morning of Sunday, June 28, 1914.

The first four—Muhamed Mehmedbašić, Nedjelko Čabrinović, Vaso Čubrilović, and Cvjetko Popović—lined both sides of Appel Quay in front of the Sarajevo police station. Another conspirator, Gavrilo Princip, stood at the intersection with Franz Josef Street, where the road turned to cross the River Miljacka over the Latin Bridge. Beyond the intersection, the ringleader, Danilo Ilić, was pacing back and forth along the quay, overseeing the operation. Finally, the seventh plotter, Trifun Grabež, was posted near the intersection with the Kaiser Bridge, in the “last chance” position.

They were about to change the course of history.

The Target

Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the thrones of Austria and Hungary, had come to Bosnia to observe the empire’s annual military maneuvers, and only agreed to visit the provincial capital at the insistence of the Austrian governor of Bosnia, Oskar Potiorek. The news of his visit had angered Bosnian and Serbian political activists, who viewed it as more imperialist overreach by the Austrian-Hungarian empire.

Several days before, on Thursday, June 25, the archduke and his beloved wife, Sophie Chotek, Duchess of Hohenberg, left their hotel in the nearby spa town of Ilidža to pay a surprise visit to the Sarajevo bazaar, where they did some shopping amid enthusiastic crowds. Then, on Friday and Saturday, while the archduke was off observing the army maneuvers, Sophie returned on her own to visit various churches, mosques, and charitable institutions, again meeting with a warm welcome; on Saturday evening she gushed, “Everywhere we have gone here we have been greeted with so much friendliness,” even from Bosnian Serbs.

But today was the official event, the day for pomp and circumstance (and, coincidentally, the archduke and Sophie’s wedding anniversary). Accordingly, the itinerary was planned more or less down to the minute: After attending a private mass in Ilidža, the couple arrived at the Sarajevo train station at 9:40 a.m., then paid a visit to the local army barracks, where Ferdinand reviewed the troops. By 10 a.m. they were on their way again, heading east on Appel Quay to City Hall to meet the local dignitaries.

They rode with Governor Potiorek in the back of a brand new Gräf & Stift “Double Phaeton” open-topped touring car owned by Lieutenant Colonel Count Franz von Harrach, who was serving as the archduke’s bodyguard and sat in front with the driver, Leopold Lojka. Theirs was third in a motorcade of seven vehicles—the first carrying Sarajevo’s chief of special security and three policemen, the second the mayor and chief of police, and the rest various members of the archduke’s entourage, as well as provincial officials and prominent local businessmen.

The motorcade proceeded at a leisurely pace so the crowds could see the archduke, who was nervous about assassins but also felt compelled to appear casual and unconcerned. There were no troops lining the streets—Potoriek insisted, implausibly, that the populace was happy under his benevolent administration—and in fact most of the spectators seemed enthusiastic, shouting cheers of Zivio! (“long may he live!”) as the archduke’s car passed. But the archduke’s intuition was better than the governor’s.

The Bomb

The first conspirator, Mehmedbašić, lost his nerve—but the second, Čabrinović, was more determined: Around 10:15 a.m., he threw a small bomb at the archduke’s car. The device bounced off and exploded under the following vehicle, injuring two military adjutants, Count Erich von Merizzi and Count Alexander Boos-Waldeck. Čabrinović immediately took a cyanide pill and threw himself in the Miljacka, but the poison didn’t work, leaving him at the mercy of enraged onlookers, who fished him out of the shallow river and administered a severe beating before the police took him into custody.

Now the archduke’s motorcade sped away to City Hall, too fast for any of the other would-be assassins to make an attempt; assuming that Čabrinović would crack under interrogation, their next priority was to avoid being rounded up—all except Princip who, coolheaded as always, meandered across the street to stand in front of Moritz Schiller’s delicatessen at the corner of Appel Quay and Franz Josef Street, along the planned return route for the archduke’s motorcade. (The story that Princip went to Schiller’s to order a sandwich is probably a myth.)

Meanwhile, the motorcade proceeded to City Hall, where Franz Ferdinand couldn’t conceal his anger. When the mayor (who’d been riding in a lead car and was still unaware of the bomb attempt) tried to begin his official greeting, the archduke interrupted, “Lord Mayor, what is the good of your speeches? I come to Sarajevo on a friendly visit and someone throws a bomb at me. This is outrageous!” However, Sophie whispered something in her husband’s ear and he regained his composure, bidding the mayor to finish his speech and then giving his own prepared speech in return. Next came the presentation of local worthies including Muslim, Christian, and Jewish community leaders, followed by an official reception, where Franz Ferdinand tried to make light of the assassination attempt, joking, “Today we shall get a few more little bullets.” By 10:45 a.m., the meet-and-greet was over and they were on their way again.

At this point, the itinerary called for the archduke to attend another reception at a local museum, but instead he gallantly insisted on visiting the hospital to see the military adjutants, Merizzi and Boos-Waldeck, who were being treated for injuries sustained in the bomb attempt. The original plan had the motorcade turning right on Franz Josef Street, the shortest route to both the hospital and museum, but the archduke’s security team, fearing more assassins might be lying in wait along this route, decided to change things up and take the long way, back down Appel Quay. They also switched the order of the cars, with the mayor and chief of police in the lead car and the archduke, Sophie, and Governor Potiorek in the second. Count von Harrach insisted on riding on the left running board to shield the archduke from the south (river) side of the quay, where the last attack had originated.

The Attack

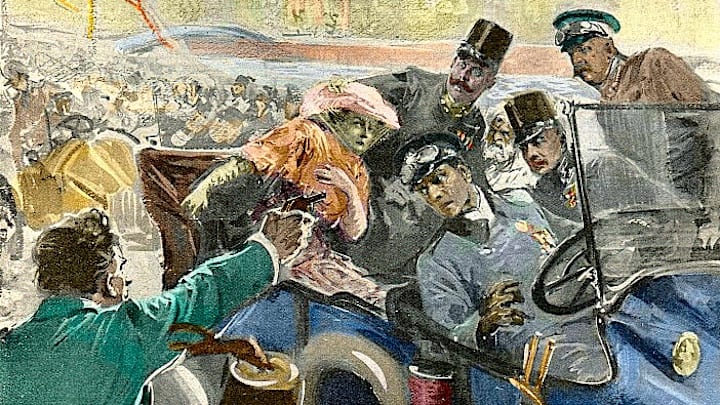

Unfortunately, the driver of the lead car either wasn’t informed of the change in plans or simply forgot, and mistakenly turned right on Franz Josef Street, as called for in the original itinerary. Lojka, apparently confused, also began turning but Potiorek told him to stop, then called out to the lead car to turn around so they could resume their journey along the correct route. As the driver of the lead car began to maneuver about in the narrow street, Princip, still standing in front of Schiller’s delicatessen, was astonished to see his target sitting in the back of the second car, just five paces away.

Without hesitation he stepped forward and fired two shots, hitting the archduke in the neck and Sophie in the lower abdomen. Chaos ensued as a crowd of bystanders attacked Princip and wrestled him to the ground, while Lojka backed up to get away from the melée. Harrach, who was still clinging to the other side of the car, later recounted:

“As the car quickly reversed, a thin stream of blood spurted from His Highness's mouth onto my right cheek. As I was pulling out my handkerchief to wipe the blood away from his mouth, the Duchess cried out to him, ‘For God’s sake! What has happened to you?’ At that she slid off the seat and lay on the floor of the car, with her face between his knees. I had no idea that she too was hit and thought she had simply fainted with fright. Then I heard His Imperial Highness say, ‘Sophie, Sophie, don’t die. Stay alive for the children!’ At that, I seized the archduke by the collar of his uniform, to stop his head dropping forward and asked him if he was in great pain. He answered me quite distinctly, ‘It is nothing!’ His face began to twist somewhat but he went on repeating, six or seven times, ever more faintly as he gradually lost consciousness, ‘It’s nothing!’ Then came a brief pause followed by a convulsive rattle in his throat, caused by a loss of blood. This ceased on arrival at the governor’s residence. The two unconscious bodies were carried into the building where their death was soon established.”

In the days to come, all the conspirators except Mehmedbašić were apprehended, and anti-Serb riots broke out in Bosnia as Catholic Croats and Bosnian Muslims took the opportunity to loot their neighbors’ homes and businesses. Further afield, European public opinion was sympathetic to the archduke and Austria-Hungary: Then, as now, terrorist attacks were viewed as barbaric and counterproductive, and newspapers like Britain’s Daily Mirror stirred readers’ emotions by dwelling on the archduke’s “pathetic last words to his wife” and the “poignant fate” of their three orphaned children following the “ghastly tragedy.” Kaiser Wilhelm II, who was hosting the British fleet’s visit to Kiel, blanched on hearing the news: He considered the archduke and Sophie personal friends.

The Aftermath

But, ironically, the first response in Vienna was a secret (or not so secret) feeling of relief. While no one was happy that Franz Ferdinand was dead, exactly, the court had long been perturbed by his plans to reform Austria-Hungary by either adding a third monarchy representing the Slavs or—even more radically—transforming it into a federal state. Both options would have met with bitter opposition in the Hungarian half of the Dual Monarchy, where the Magyar aristocrats would see their influence diminished, and this looming conflict threatened to tear the fragile empire apart. Thus, the elderly Emperor Franz Josef displayed a strange combination of horror and resignation when he was informed of his headstrong nephew’s demise:

“On hearing the news… the emperor collapsed into the armchair at his desk as if struck by a thunderbolt. He remained motionless for a long time. At the end he rose, paced the room a prey to the most violent agitation, his eyes rolling with terror. ‘Horrible! ... Horrible!’ was the only word which escaped his lips. At last he seemed to have somewhat recovered his self control, for he exclaimed suddenly as if speaking to himself: ‘The Almighty is not mocked! ... A higher power has restored that order which I, unfortunately, was not able to maintain.’”

In the same vein, the imperial ambassador to Berlin, Count Szőgyény, confided to the former German chancellor Bernhard von Bülow that the assassination was “a dispensation of Providence,” as the archduke’s ascent to the throne “might have given rise to serious conflict, perhaps even civil war.”

In keeping with this attitude, and the court’s contempt for the archduke’s morganatic wife, the funeral arrangements were very modest: There were few signs of public mourning as the couple’s remains arrived back in Vienna on July 2, and practically no one attended the ceremonial lying-in-state in the Hofburg palace or the funeral at the archduke’s rural retreat at Artstetten on July 3. In the crowning act of petty cruelty, Lord Chamberlain Prince Alfred of Montenuovo even forbade the archduke’s three orphaned children (now stripped of all royal privileges) from saying goodbye to their dead parents.

But this didn’t mean his death couldn’t serve some purpose. After years of Serbian defiance, the assassination provided a perfect opportunity to settle accounts with the Slavic kingdom by force, as the Austrian chief of the general staff, Conrad von Hötzendorf, had so frequently advocated. This wasn’t just about avenging a single crime: The time had come to reverse the tide of Slavic nationalism, which posed an existential threat to the multiethnic empire. In short, war was the only option, even at risk of a wider conflict with Serbia’s great Slavic patron, Russia. In a meeting with his staff on June 29, 1914, Conrad outlined the case he would shortly present to Emperor Franz Josef, Foreign Minister Count Berchtold, and Hungarian premier Count István Tisza:

“Austria-Hungary cannot let the challenge pass with cool equanimity nor, after the blow on the one cheek, offer the other in Christian meekness, neither is it a case for a chivalrous encounter with ‘poor little’ Serbia, as she likes to call herself, nor for atonement for murder—what is now at issue is the strictly practical importance of the prestige of a great power … The Sarajevo outrage has toppled over the house of cards built up with diplomatic documents … the monarchy has been seized by the throat and forced to choose between letting itself be strangled and making a last effort to defend itself against attack.”

One month after the assassination, Austria-Hungary, backed by its Central Powers [PDF] ally Germany, declared war on Serbia. Russia began mobilizing its troops. Germany then declared war on Russia, triggering troop mobilization in France, aligned with the Allied Powers. On August 2 and 3, Germany invaded Luxembourg and Belgium and declared war on France, forcing their ally Great Britain to declare war on Germany. Finally, on August 6, Austria-Hungary declared war on Russia, engaging Europe in a conflict stretching from Ireland to Turkey.

Two people were dead in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914. Millions more would soon follow.

Read More Stories About World War I:

A version of this story was published in 2014; it has been updated for 2024.