The First World War was an unprecedented catastrophe that killed millions and set the continent of Europe on the path to further calamity two decades later. But it didn’t come out of nowhere. With the centennial of the outbreak of hostilities coming up in 2014, Erik Sass will be looking back at the lead-up to the war, when seemingly minor moments of friction accumulated until the situation was ready to explode. He'll be covering those events 100 years after they occurred. This is the 90th installment in the series.

October 28, 1913: Showdown in Constantinople: The Liman Von Sanders Affair

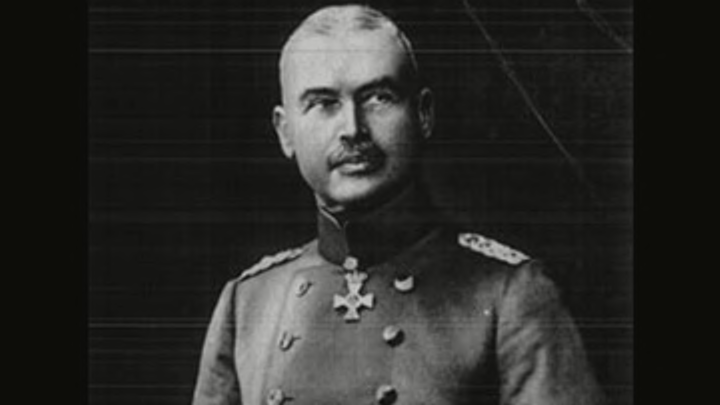

On October 28, 1913, Lieutenant General Otto Karl Victor Liman von Sanders (top) signed a contract with Mahmud Muhtar Pasha, the Turkish ambassador to Berlin, putting von Sanders in charge of training the Ottoman army, which was in dire need of reform and modernization following its disastrous defeat in the First Balkan War.

At first glance, von Sanders’ mission was fairly routine. As Europe’s Great Powers jockeyed for position around the planet in the first years of the 20th century, one common way of extending their influence beyond the bounds of colonial empires was helping backwards states upgrade their militaries with European methods and equipment. The British had dispatched several naval missions to Constantinople to bring the Turkish navy up to snuff (with limited success); it was only natural for the Turks to turn to Germany, Europe’s preeminent land power, to reform their army.

But the scope of von Sanders’ assignment extended even further: In addition to providing training and technical advice, the retired artillery officer would assume command of the Turkish garrison guarding the capital, Constantinople. Although von Sanders was supposed to be serving the Turkish government, in effect a key part of the Ottoman military would now fall under German control—a power grab guaranteed to raise hackles among rival Great Powers, who had their own designs on Ottoman territory and resented the German intrusion.

Sure enough, when news of the von Sanders mission began circulating in November 1913, one Great Power in particular blew a fuse. The Russians had long dreamed of conquering Constantinople and the Turkish straits in order to secure maritime access to the Mediterranean and the oceans beyond; a hostile power in possession of the straits could bottle up Russia’s Black Sea navy and cut off its grain exports, a key source of foreign currency. Russia’s foreign trade had suffered badly after the Turks closed the straits during their war with Italy in 1912; now it looked like the Germans were plotting to take control by slipping in the back door.

With the Balkan conflicts and Albanian crises barely a memory, Europe suddenly found itself on the brink of war yet again.

The Zabern Affair

While Germany’s foreign policy stirred tensions abroad, internal political divisions were growing deeper at home, as the conservative, authoritarian government faced mounting criticism over the German military’s domination of civil society.

Along with the rest of Alsace and the neighboring province of Lorraine, the small town of Zabern (French: Saverne) had been part of France until the Franco-Prussian War of 1871, when the victorious Prussians annexed it to the newly formed German Empire; unsurprisingly, four decades later there was still some lingering resentment of the German administration among the Alsatians, who tended to view themselves as a culturally distinct group with their own history and identity, separate from both Germans and French.

In this situation it would have made sense for the German government to try to ease tensions by minimizing the more visible elements of the German occupation, for example by employing native Alsatians for garrison duty. But in typical Teutonic fashion German administrators did the exact opposite, bringing in Prussian troops to guard the border towns on the theory that the Alsatians might be disloyal—not exactly a policy designed to demonstrate trust or build confidence. And the stubborn Germans were about to discover the simple truth confronted by so many occupiers before and since: that a bunch of bored teenagers with access to alcohol aren’t necessarily the subtle instruments of statecraft one might hope.

On October 28, 1913, Günter Freiherr von Forstner, the 19-year-old second lieutenant of the Prussian 99th Regiment garrisoned in Zabern, gave a little pep talk to his troops in which he advised them, “If you are attacked, use your weapon, and if you stab a Wackes in the process, then you'll get ten marks from me”—“Wackes” being a derogatory term for Alsatians. Forstner’s insensitive comment might have passed unnoticed if some of his own soldiers hadn’t relayed it two local newspapers, which started beating the drums for disciplinary action against the second lieutenant.

Interpreting this as an attack on their authority, Forstner’s superiors refused to reprimand the junior officer, transforming the matter from a local embarrassment into a national scandal, as socialists and other anti-militarists (as well as “respectable” bourgeois politicians) seized on the incident as proof that the German military didn’t consider itself subject to civilian oversight. Before it was over the Zabern Affair badly damaged the reputation of Kaiser Wilhelm II and almost brought down the government, while revealing profound divisions in German society.

See the previous installment or all entries.