The First World War was an unprecedented catastrophe that killed millions and set the continent of Europe on the path to further calamity two decades later. But it didn’t come out of nowhere. With the centennial of the outbreak of hostilities coming up in 2014, Erik Sass will be looking back at the lead-up to the war, when seemingly minor moments of friction accumulated until the situation was ready to explode. He'll be covering those events 100 years after they occurred. This is the 87th installment in the series.

September 29, 1913: Franz Ferdinand Opposes War with Serbia

After months of arguing, cajoling, pestering, and pleading, by September 1913 Austrian chief of staff Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf had finally won over foreign minister Count Leopold von Berchtold to his point of view: The upstart kingdom of Serbia, burning with ambition to liberate its ethnic kinsmen in Austria-Hungary’s neighboring Balkan provinces, represented an implacable existential threat to the Dual Monarchy which could only be eliminated by war.

Conrad was helped in his campaign by the events of the Balkan Wars, when Serbia and its allies carved up the European territories of the Ottoman Empire, then fought each other over the spoils; informed opinion held that the Serbs would next try to fulfill their national destiny by dismembering Austria-Hungary. The Austro-Hungarian Empire’s southern Slavic populations in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia already complained of oppression (resentment which was hardly allayed by Bosnian governor Oskar Potiorek’s decision to decree a state of emergency in the province in May 1913). The sense of looming disintegration was only heightened by a rash of assassination attempts against Imperial officials by Slavic nationalists and anarchists.

In short, Conrad’s fears were no paranoid fantasy: the Empire really was coming apart at the seams, and Slavic nationalism seemed to be the main (though certainly not the only) culprit. Thus when Serbian troops invaded Albania in September 1913, threatening to undo all Berchtold’s work creating the new nation, the foreign minister didn’t need to be persuaded that the time had come for a decisive military response.

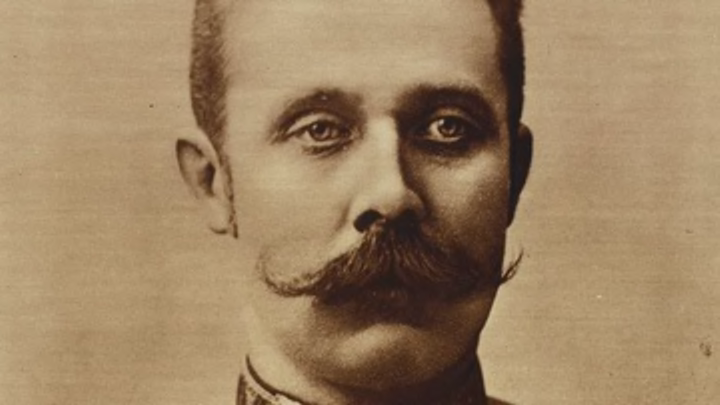

But one key figure still stood in the way: Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the throne, who remained focused on Italy as Austria-Hungary’s real long-term enemy. Never shy about sharing his opinions, Franz Ferdinand shrugged off Berchtold’s warnings about the Serbian threat—“all such Serb horror stories leave me cold”—and made no secret of his opposition to war, predicting (correctly) that it would lead to war with Serbia’s patron Russia as well. In February 1913 he gave an unusual toast at a public event: “To peace! What would we get out of war with Serbia? We’d lose the lives of young men and we’d spend money better used elsewhere. And what would we gain, for heaven’s sake? Some plum trees and goat pastures full of droppings, and a bunch of rebellious killers. Long live restraint!”

In fact the Archduke had a falling out with Conrad over this issue, repeatedly chastising the chief of staff for urging Emperor Franz Josef to attack Serbia. In the summer of 1913 he wrote to Berchtold: “Excellency! Don’t let yourself be influenced by Conrad—ever! Not an iota of support for any of his yappings at the Emperor! Naturally he wants every kind of war, every kind of hooray! rashness that will conquer Serbia and God knows what else… It’s be unforgivable, insane, to start something that would pit us against Russia.”

Now, as different factions vied for the Emperor’s ear amidst another Albanian crisis, Franz Ferdinand’s attitude was yet again the decisive factor. On September 29, 1913, Conrad told Berchtold “Now would be the opportunity to put things in order down there. An ultimatum, and if Albania is not evacuated in twenty-four hours, then mobilization.” Berchtold replied that he personally supported military measures, but “felt no confidence that authoritative quarters would stand firm.” Conrad, ever hopeful, pointed out that “On peace and war the decision lies solely with the Emperor”—but there was no escaping the fact that the elderly monarch felt obliged to heed the vehemently expressed views of his nephew the Archduke. Once again the foreign minister and chief of staff found their plans frustrated by the heir to the throne.

Franz Ferdinand wasn’t totally oblivious to the threat posed by Serbia, but he hoped to resolve things with a (somewhat vague) plan to reform Austria-Hungary by adding a third monarchy representing the Slavs, or perhaps even remaking the Empire as a federal state, which might then absorb Serbia peacefully. Unsurprisingly his plan was bitterly opposed by Serbian nationalists, who aspired to become the nucleus of a new “Yugoslav” state, not a mere appendage of a decadent multinational empire.

Nevertheless, Franz Ferdinand—recently appointed inspector general of the armed forces—pressed ahead with his plans to attend the upcoming annual maneuvers in Bosnia in June 1914, followed by a visit to the provincial capital of Sarajevo; while the Archduke hoped to avoid war with Serbia and conciliate the Empire’s own Slavs, he also understood that a little saber-rattling could help keep the peace. On September 29, 1913, Conrad met with Potiorek, the provincial governor, to begin making arrangements for Franz Ferdinand’s visit, including provisions for security (which in the event proved sadly lacking).

Inevitably, word of the Archduke’s impending visit started to spread. The Serbian ambassador to Vienna, Jovan Jovanović, later recalled: “From the month of December [1913] onwards the maneuvers in Bosnia were spoken of in Vienna. The Inspector General of the Austro-Hungarian army was to take part both as future Emperor and Commander-in-Chief. It was to be, as was said towards the end of 1913, a lesson and warning to the Serbs both of Bosnia and Serbia.” Among those certain to hear of the Archduke’s planned visit was Dragutin Dimitrijević (“Apis”), the chief of Serbian military intelligence and head of the ultra-nationalist secret society known as the “Black Hand.”

See the previous installment or all entries.