Erik Sass is covering the events of the war exactly 100 years after they happened. This is the 299th installment in the series. Read an overview of the war to date here.

January 8-10, 1918: Wilson Presents ‘Fourteen Points,’ House Approves Suffrage Amendment

By the beginning of 1918, it was clear to close observers that the United States of America was gearing up to make a significant contribution to the Allied war effort, though it would take some time (and President Woodrow Wilson insisted it was only as an “Associated,” not an Allied, power, limiting America’s obligations to Britain and France).

The size of the American Expeditionary Force was set to increase from 176,000 troops in January to 424,000 in May, 722,000 in June, and 966,000 in July, with troop shipments expedited in response to pleas from the French during the dark days of the German spring offensives beginning in March. Meanwhile America's financial contributions were soaring, with loans to Britain more than doubling from $1.5 billion in 1917 to $3.6 billion in 1918.

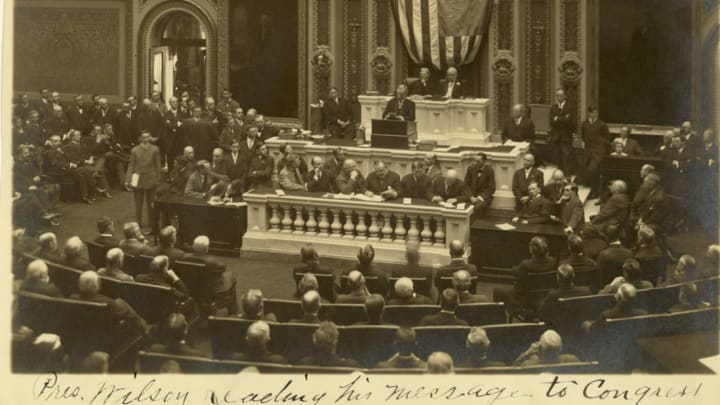

However, it remained to be seen what vision Wilson would present for the post-war order, now that America was in the driver’s seat, not just providing critical manpower but also supplying the Allied war effort and holding billions of dollars of their debt. On January 8, 1918 Wilson sketched out some of the foundational elements of his peace program, the “Fourteen Points,” in a speech to a joint session of Congress on “War Aims and Peace Terms.”

Wilson began by noting that Russia had made a reasonable peace offer to the Central Powers at Brest-Litovsk, but had been spurned, as the latter intended “to keep every foot of territory their armed forces had occupied—every province, every city, every point of vantage—as a permanent addition to their territories and their power.” Denouncing the brazen imperialism of the authoritarian governments that ruled the Central Powers, which were running roughshod over their parliaments, Wilson went on to lay out the principles of a just world order built on the democratic ideal that all governments must have the consent of the governed. However, in this, as in his other idealistic programs, the goals remained vague, unrealistic, or contradictory.

First among the Fourteen Points, Wilson insisted that the age of secret alliances, of the sort which brought Europe to war, was over: henceforth all treaties and covenants should be open, public knowledge. He also called for free navigation on the seas, implying the lifting of the Allied naval blockade and the end of U-boat warfare, free trade, and arms reduction agreements.

Most of these proposals were reasonable enough, but others were less plausible. For example, during the adjudication of colonial disputes in which European powers drew and redrew the boundaries of African and Asian possessions, the Europeans were somehow supposed to take into account the interests of the colonial populations themselves—even though the whole colonial enterprise limited native voices to exclude them from politics by design. Calling for self-determination and new national boundaries in Europe, Wilson ignored the fact that the Allies couldn’t even reconcile their own contradictory postwar territorial claims (see cartoon below). Returning to open diplomacy, how could anyone guarantee that countries weren’t engaged in secret alliances behind the scenes?

Meanwhile, it came as no surprise that Wilson’s most immediate and concrete demands—including the Central Powers evacuating all their conquests in Russia, Poland, France, Belgium, and the Balkans—were non-starters for the Germans, as the military party led by chief of the general staff Paul von Hindenburg and his chief strategist, Erich Ludendorff, still believed the war could be won, allowing Germany to keep at least some of her conquests. Wilson’s call for Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire to grant full autonomy to its various subject peoples was, in effect, calling for the dissolution of Germany’s allies.

Coincidentally, on January 8, 1918 Ludendorff also began planning Germany’s giant springtime offensive, “Operation Michael,” in hopes of knocking Britain and France out of the war with 1 million German troops transferred from the dormant Eastern Front, before American troops could arrive in France in large numbers. The mighty blow would fall in late March 1918.

U.S. House Passes Women’s Suffrage Amendment

On January 10, 1918 the U.S. House of Representatives passed the 19th Amendment, later known as the Women’s Suffrage Amendment, by the necessary two-thirds majority—but a one-vote margin. This was a huge breakthrough, but by no means the end of the struggle: the Senate would reject the bill twice before approving the amendment for ratification by the states and final adoption on August 18, 1920.

The suffrage movement, demanding voting enfranchisement for women, dated back to the mid-19th century, when it originated in connection with both the American abolitionist and temperance movements, thanks to activists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Carrie Chapman Catt, Clara Barton, and others. New western territories gave a boost to the cause: in 1869 the Wyoming territory granted women the right to vote, perhaps in hopes of attracting more women of marriageable age for their male-dominated frontier population, followed by Utah (1870), Washington territory (1883), Kansas (1887), and Colorado (1893)—the latter delivered by a referendum, with 35,798 or 55 percent of male voters voting in favor. A majority of male voters in California chose to give women the right to vote in 1911.

However, the First World War galvanized the women’s suffrage movement across the west, as women demanded recognition of their many personal sacrifices and contributions to the war effort, giving the issue a sense of inevitability. In August 1917 the debate was already considered old news in enlightened circles, according to Mildred Aldrich, a retired American writer living in France, who wrote:

I imagine we have buried for all time what has for so many years been known as the “women question.”… The beauty of the whole matter is that woman has won by acts, not words. She has won by doing a woman’s work ... In every branch of war work done by unarmed men, women have appeared and shown the same courage and the same unfailing patriotism as men … No wonder the suffrage excitement is already ancient history.

Although American women would have to wait a few more years, neutral Denmark adopted women’s suffrage in 1915, and a number of Canadian provinces followed in 1916-1918. Russia’s post-revolutionary Provisional Government granted women the right to vote in 1917. Britain’s Parliament passed the Representation of the People Act, granting the right to vote to 8.4 million female householders, on June 19, 1917, taking effect with elections in December 1918. Germany enshrined women’s suffrage in the Weimar constitution adopted in 1919.

Women’s Work, Women’s War

The wave of women’s suffrage reflected massive social changes that took place during the war, shifting the balance of power between the genders, as European women shouldered heavy duties to sustain the war effort but also gained economic leverage thanks to higher-paid work. In 1917 Julia Stimson, an American chief nurse, proudly noted the changes wrought by the war in Britain, especially the influx of women into what was previously men’s work—while wondering about the long-term consequences:

From the highest to the lowest each woman has her work … Of course the street-sweeping by women is a kind of war work, and the bus conductoring, and delivering mail and telegrams, and driving cars and ambulances. The streets are full of women in uniforms of all sorts, all smart and business-like. Women in England are coming into their own … What is to happen after the men come back can well fill the [mind] … for a change is taking place here that can never be undone.

The huge changes were evident on both sides of the conflict. Ernest Bullitt, an American woman visiting Germany, wrote in her diary in June 1916:

The munition factories pay the highest wages. The average wage for these women now is about eight marks a day. In Germany, as in the other warring countries, there is little the women are not doing. Sturdy peasant girls pace the streets, dig ditches, lay pipes. Women drive the mail wagons and delivery wagons, deliver the post, work in in open mines, work electric walking cranes in iron foundries, sell tickets and take tickets in railway stations, act as conductors in the subway.

Later Bullitt noted that female industrial workers were central to maintaining Germany’s war effort—and like Stimson, predicted a gender clash when the war ended:

There are great numbers in the metal industries doing half-skilled work, and also women doing the skilled work. They manage the travelling cranes in iron and steel foundries, a thing no employer believed was possible. They do what is called “electro-technical” work … They dig the coal and also load the cars … The employers declare they wish to keep the industries which they have entered, and it will be quite a fight to prevent their going on working in many of them.

The numbers of women employed were in keeping with the scale of the conflict. In Britain, in addition to organizations like the Women’s War Auxiliary Corps, which allowed thousands of women to serve in non-combat military roles, and the Women’s Land Army, which employed a quarter-million women in agricultural work, 1.7 million women entered the labor force during the war, bringing the total number of women at work to 4.9 million by 1918, and increasing the proportion of women in the industrial workforce from a quarter to nearly half (46.7 percent).

In France, women constituted 38 percent of the country’s total work force in 1914 but this increased to 46 percent in 1918, including 430,000 women who made up 30 percent of the total workforce for the arms industry. In Germany the proportion of women in the labor force jumped from 22 percent in 1913 to 35 percent in 1918, including 700,000 in the armaments industry. In Austria-Hungary 42 percent of the empire’s heavy industrial workforce was female by the end of the war.

The move to well-paid factory jobs was economically liberating, allowing women to scale the wage ladder from traditional, poorly compensated female employment. In Britain the number of women working in domestic service fell from 1.66 million to 1.26 million over the course of the war, and the number of British women in trade unions jumped from 437,000 in 1914 to over 1.2 million in 1918, reflecting their growing economic and political clout.

Across Europe, governments and private businesses were compelled to provide childcare for female workers, sometimes in the form of “factory nurseries.” Bullitt noted other concessions to women workers in Germany in her diary in June 1916:

Employers are not allowed to discharge women for child-bearing. They must give them two weeks’ holiday before the child’s birth, and four weeks after. During this period they get two thirds of their wages from their sickness insurance. Also, they may get their doctor and medicines free.

However, not all the new employment was new or liberating, especially in sectors like agriculture. Across Europe, peasant women did their best to maintain homesteads in the absence of husbands and sons, relying on older children for labor and using the local church or informal arrangements for childcare for the rest. Elizabeth Ashe, an American woman volunteering with the Red Cross, described one guest of a “refuge” for women with children. “We saw a woman who was here for a few days’ rest, she works in the fields at night with a helmet and gas mask, because the shells drop on her so in the day time she can not work," she wrote. "She has a baby two months old whom she leaves in this refuge.”

Although used to hard work, many peasant women were unused to the physical strain involved in activities like horse-drawn plowing. Emilie Carles, a Frenchwoman who maintained the farm while her brother was a way, remembered:

Before he left, Joseph taught me to plow. The hardest part wasn’t so much dealing with a mule or yoke of cows as holding on to the handle. I was not tall. I remember we had an ordinary plow, the swing type, with a handle designed for a man. It was far too high for me. When I cut furrows with that contrivance, I got the handle in the chest or face every time I hit a stone.

Nothing Romantic About It

It is important not to romanticize the plight of ordinary women separated from male loved ones and breadwinners and plunged into hardship and uncertainty. Peasant women faced acute financial pressures as they struggled with reduced incomes. One war widow wrote to the French journalist Rene Bazin, explaining her reasons for throwing in the towel:

Although I myself drive our horses, who are too strong to be entrusted to the old men or the boys, and I load the wagons, I’m not making the value of the rental contract owing to the poor harvest and the increases in wages … At present, I can only sow wheat in two-thirds of the land that should be planted in grain. Thus, certain deficit for next year. If I stay on, the little that my husband left to his children will be swallowed up.

At the same time industrial work was hardly a panacea. The fact is, like their peasant counterparts numerous women cracked under the dual strains of factory work and caring for their families. Madeleine Zabriskie, an American socialist activist visiting Germany in 1916, received the following description of one woman from a social worker at a German arms factory:

The woman you inquired about lives in a suburb. She must have been good-looking when she was young, but she has given birth to 12 children, the oldest is thirteen and the youngest six months. Four of her children died … Her husband worked for nine years in the factory. When the war broke out he was mobilized and joined the army August 4, 1914. Until then they had been happy, but that changed everything. They had to move out of their house. They took an apartment of two rooms. It was crowded with nine people in two rooms, but they could not afford anything better. The birth of the last child caused the mother great suffering and she had to give up her factory work … The woman is weak and much shaken in health. At night she worries about her husband and cannot sleep. She weeps a great deal and really the burden laid on her is almost too heavy.

Another German woman wrote to her husband, a POW in France, in August 1917:

I am so sick and tired of human life that I want to cut my own and my children’s throat, I am not afraid of committing a sin, after all I am forced by misery. You have to be the most stupid person on God’s earth when you have children. They take the breadwinner away from the children and let them starve to death, they are crying for bread the whole day long … I have got our four little children, none of them can help earn some money. I have to feed them, wash them, have to mend their clothes, etc. I have to stand in the street all day long and wait for hours until I get a few things to eat … But who cares about a soldier’s wife with a lot of little children, she can perish together with her children.

See the previous installment or all entries, or read an overview of the war.