A Christmas tree may occupy a corner of your living room, and your consciousness, for only a few weeks each winter. But it and its evergreen ilk are a full-time, year-round preoccupation at the thousands of farms across the country that grow holiday pines and firs and spruces. And there’s a lot more to the business than sticking trees in dirt and then chopping them off at the trunk a few years later. Mental Floss tracked down some of the men and women working on farms around the nation to learn some of the secrets of their trade.

1. THE TREES THEY GROW NOW ARE DIFFERENT THAN THE TREES THEY GREW FOR OUR PARENTS.

Americans love firs. The type available at your local tree stand or choose-and-cut farm depends on conditions in each of the states that grow them. Rainy weather in Oregon—which sells some 7 million trees a year, the most of any state—is favorable to noble firs. Frasers thrive in North Carolina’s mid-range elevations, where it’s cold in winter and cool in summer; balsams are native to Vermont. But 40 years ago, folks were partial to un-manicured spruces and Scotch pines. These trees were “taller, spindlier, and had barren gaps between the branches, which were conducive to [decorating with] candles,” Luke Laplant, who sells trees from Vermont’s Windswept Farms on the streets of Brooklyn, tells Mental Floss.

What can we expect for the next big trend in trees? Marsha Gray, director of the Michigan Christmas Tree Association, says that growers have lately been experimenting with exotic species like short-needled Turkish and compact Korean firs.

2. THEIR CUSTOMERS HAVE SOME … UNUSUAL IDEAS.

Doug Hundley, a retired grower from North Carolina, still laughs about misconceptions he heard from customers at the farm he owned for 30 years. To wit: They imagined that the tidy rows of trees planted on his five acres had magically sprung from seeds dropped from a nearby pine stand. In fact, tree farms are usually launched with young, 3-to-5-year-old trees purchased from specialty nurseries, which are planted in 5-foot by 5-foot grids— about 1700 trees per acre. An acre of additional trees is planted every year, and after eight or nine years, “You’ll have that first acre starting to come ready” to sell, Hundley tells Mental Floss. Trees to replace them go in the ground soon after the initial batch comes down, staggered about a foot away from the leftover stumps, which quickly rot away.

Many of Laplant’s customers ask about adding supposed “preservatives,” like Sprite or aspirin, to the tree water in the stand. But he says these stunts are unnecessary for keeping trees green. “Just make sure you make a fresh cut to the bottom of the trunk before you put it in the stand, so it doesn’t scar over, and check it for water every day,” he advises.

3. THEY HAVE A DIFFERENT TASK FOR EVERY SEASON.

Christmas tree farmers are like farmers of every other crop: They rarely have time for vacations. There’s a brief lull in activity during winter, once the year’s trees have been cut and the farm goes dormant. But otherwise, there’s work to be done in every season. Hundley explains, “Starting in March, we’re really busy planting more trees and fertilizing. In summer, we’re managing weeds and insects and shearing the trees.” Then it’s fall again—harvest time; farmers start collecting wreath-making greenery as early as October, and the actual tree-cutting lasts through December.

4. THEY WORK (REALLY) HARD TO BRING YOU THAT CONICAL SHAPE.

That stereotypical tapered Christmas tree silhouette doesn’t happen all by itself. It’s the result of heavy hand labor over time. For two months beginning in July, workers head out to the fields with knives and other tools to shear the trees, cutting off new branches and needles from the sides in order to slow down growth and encourage a fuller, more pleasing shape. Every tree gets whittled down like this every year, which is why it takes almost a decade for it to reach its desired height of six or seven feet, rather than, say, four years.

5. NATURE IS CRUEL, BUT SCIENCE IS TRYING TO HELP.

The number one blight on Fraser firs is phytophthora root rot, which causes needles to turn yellow and fall off. This troublesome oomycete (related to algae) can’t be controlled with chemicals. So, evergreen farmers have been attempting to breed disease-resistant trees: Frasers are grafted onto rootstock from Abies firma (a.k.a. the momi fir). It’s native to Japan, and it’s supposed to have serious oomycete-repelling properties. Hundley says positive effects from these efforts have been slow to manifest, though.

6. THEY ALL AGREE: FAKE CHRISTMAS TREES ARE THE ENEMY.

“Nine years in the house, nine million years in the landfill.” That’s a phrase popular among real-Christmas-tree farmers to describe their nemeses, plastic “pines”—many of which are imported into the U.S. from China. Hundley remarks that sustainability-minded Teddy Roosevelt banned Christmas trees from the White House during his time in office, in order to protect trees growing wild in forests. But, “We don’t harvest wild” anymore, says Hundley, adding, “Would you buy artificial roses to give your [spouse] on Valentine’s Day?”

7. ENVIRONMENTALISM IS PART OF THE BUSINESS.

Unlike their plastic counterparts, real trees get returned to the land once we’re done with them, in the form of mulch. Farms full of live trees can also offer environmental benefits: The trees hold the soil against erosion, and they provide habitat for hosts of beneficial critters such as ladybird beetles and spiders, as well as birds, rabbits, and deer. These farms’ secondary function as wildlife hotels has caused growers to adopt more eco-friendly pest management techniques in the last 25 years, according to Hundley—including scaling back on pesticides. “We’re trying to create the most ecological environment we can,” he says.

8. THEY FEAR THE WASP.

Harboring wildlife comes with a downside: wasps, which are attracted to the sweet “honeydew” produced by sap-sucking aphids that feed off the trees. Wasps can be ornery when disturbed—like when crews of workers head out to shear trees in July. “The rule is,” Hundley says, “if you hear a loud humming, you put down your (very sharp) knife and take off running. And when one guy runs, everyone runs—you don’t wait to see where the sound is coming from.”

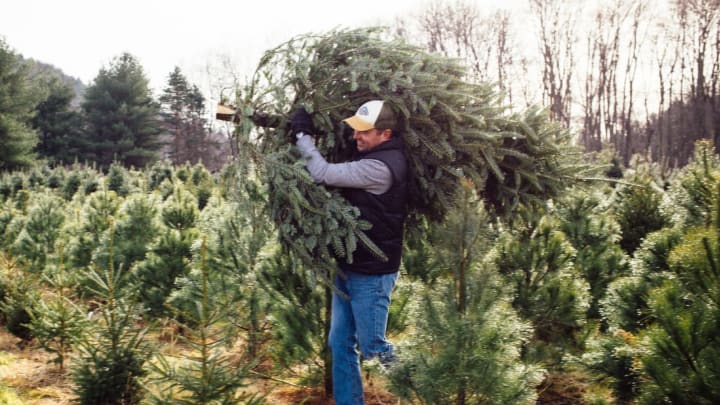

9. HARVESTING HAPPENS FAST.

There’s a short window of time in which to get trees to market—about a week or two, according to Gray. That’s because a cut tree exposed to sun and wind quickly starts to dry out and shed its needles. Growers with small farms may rely on family members to cut each tree with a chainsaw, shake the dead needles off it, then bale and stack it somewhere cool and dark. “A lot of farmers have a stand of natural evergreen forest on their property, and they’ll store the cut trees in their shade” where they retain moisture, Hundley explains. Larger producers in the Pacific Northwest, who grow millions of trees on thousands of acres, hire seasonal crews of 100 or more cutters and “slingers” to saw and stack. Gray says they use helicopters to get trees down the mountains and load them—as many as 1000 an hour—onto the flatbeds of market-bound trucks.

10. THEY WORK UP TO 16 HOURS A DAY IN THE SELLING SEASON.

“Our Brooklyn stand is open every day from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., but I get here earlier to set up and afterwards, there are deliveries and lots of cleanup,” says Laplant. To keep warm, he relies on layers of long underwear, a waterproof hooded coat, plenty of extra socks (he travels down with 40 pairs) and gloves (12 pairs). “On a rainy day, gloves get wet after you handle the first 10 trees, so you have to swap them out,” he says. Other annoyances: people who let their dogs pee on the trees or who aggressively pull at the needles then complain that they’re falling out. What makes the aggravations worth it: For Laplant and his coworkers, it’s getting delicious food delivered from all over town.