The First World War was an unprecedented catastrophe that killed millions and set the continent of Europe on the path to further calamity two decades later. But it didn’t come out of nowhere. With the centennial of the outbreak of hostilities coming up in 2014, Erik Sass will be looking back at the lead-up to the war, when seemingly minor moments of friction accumulated until the situation was ready to explode. He'll be covering those events 100 years after they occurred. This is the 72nd installment in the series.

June 7, 1913: Falkenhayn Appointed Minister of War

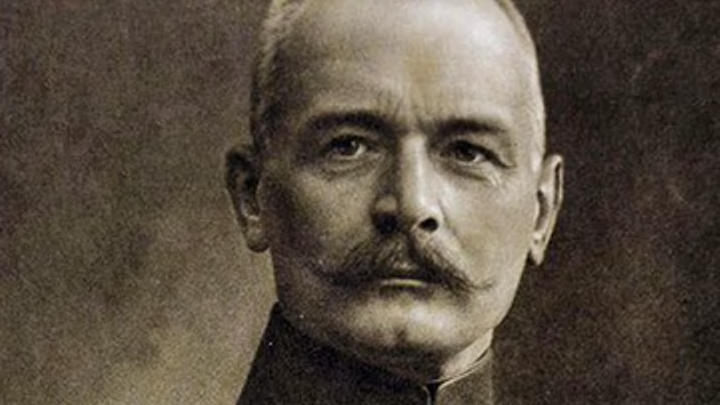

On June 7, 1913, Kaiser Wilhelm II appointed General Erich von Falkenhayn (above) to the position of Minister of War for Prussia (and in effect Germany), replacing Josias von Heeringen, who was forced out because he opposed further expansion of the standing army. A relatively junior officer, Falkenhayn—a court favorite since his reports on the Boxer Rebellion in China from 1899 to 1901—was elevated to the top administrative position over a number of older generals, reflecting the Kaiser’s personal style of government. In a little over a year, he would play a key role in steering Germany into the First World War.

Born in 1861, Falkenhayn was just a child during the Franco-Prussian War and German unification in 1870 and 1871, but was keenly aware of lingering French antipathy and increasingly anxious about the prospect of “encirclement” by France, Russia, and Britain. He also recognized the threat posed to Germany’s ally Austria-Hungary by the rise of Slavic nationalism in the Balkans, and believed that Austria-Hungary would have to deal with the upstart Kingdom of Serbia someday—preferably sooner rather than later.

In the near term, the new war minister was more receptive than his predecessor to suggestions for military expansion, reflecting the views of his imperial master. In November 1913, Falkenhayn reassured the Bundesrat that the newly expanded army was ready for action, hinting that more new recruits could be assimilated if funds were allocated, and later urged expansion of Germany’s espionage capabilities, warning that “in the great life and death struggle, when it comes, only the country which presses every advantage will have a chance of winning.” [Ed. note: The translation of this quote was slightly edited for clarity.]

In the July Crisis of 1914, Falkenhayn was even more aggressive than his rival, chief of staff Helmuth von Moltke, urging Austria-Hungary to move against Serbia as soon as possible and advising the Kaiser to declare pre-mobilization while last-ditch negotiations were still underway. He was also afflicted with the same curious fatalism displayed by other German leaders: In the final days of July, he concluded they had already “lost control of the situation,” adding, “the ball that has started to roll cannot be stopped.” As war began, he famously stated: “Even if we go under as a result of this, still it was beautiful.” Not long afterwards, Falkenhayn would replace Moltke as chief of staff after the failure at the Battle of the Marne, and in 1916 he became the architect of the bloodiest battle in history up to that point—the apocalypse of Verdun.

Russians Press Reforms on Ottoman Empire

A week after the Ottoman Empire made peace with the Balkan League, the Russians returned to the attack (diplomatically) in the east. Their devious plan to undermine Constantinople’s control over Anatolia involved arming Muslim Kurds and encouraging them to attack Christian Armenians—creating an opening for Russia to intervene on “humanitarian” grounds. After lining up diplomatic support from Britain and France (Germany and Austria-Hungary were opposed) the next step was forcing the Turks to implement decentralizing reforms granting more autonomy to the Armenians.

Click to enlarge

On June 8, 1913, a Russian diplomat in Constantinople, André Mandelstamm, presented a proposal for reforms drawn up by the Russians and Armenians which would, in essence, place ultimate authority over six Ottoman provinces in eastern Anatolia in the hands of European officials—whom the Russians would of course help appoint. Building on the groundwork laid by the provincial reforms forced on the Turks in March 1913, the June proposal called for redistricting the provinces along ethnic lines to form ethnically homogenous communes. The Sultan would appoint a European as governor-general with authority over official appointments, courts, and police (also under European commanders) as well as all military forces in the region. Armenian-language schools would be established, and land taken from Armenians by Kurds would be restored to its previous owners. Christians (Armenians) and Muslims (Turks and Kurds) would receive seats in provincial assemblies in proportion to their populations, and no Muslims would be allowed to move into Armenian areas, ensuring lasting Armenian control.

At the same time the Russians were fostering Armenian nationalism, so the Armenians would likely pursue independence from the Ottoman Empire, at which point they would be presented with a fait accompli: After breaking away, they would have no choice but to seek Russian protection and eventually unite with Russia’s Armenian population under Russian rule.

The Ottoman leaders understood that implementing the proposed reforms would mean the loss of eastern Anatolia, which they considered the Turkish heartland. Later, Ahmed Djemal—a member of the Young Turk triumvirate which ruled the empire in its final years, along with Ismail Enver and Mehmed Talaat—wrote in his memoirs: “I do not think anyone can have the slightest doubt that within a year of the acceptance of these proposals the [provinces] … would have become a Russian protectorate or, at any rate, have been occupied by the Russians.” On top of all this, the Ottoman Empire’s other populations were starting to agitate for autonomy as well: on June 18, 1913, the Arab Congress met in Paris to discuss their own demands for reforms.

In 1913 and 1914, all these factors—the humiliating defeat in the First Balkan War, nationalist movements, brazen foreign interference, plus a general awareness of stagnation and decline—provoked a sense of crisis that galvanized the Turkish leadership and population alike. With the very core of the empire threatened, their backs were against the wall and they had nothing to lose. In a letter sent May 8, 1913, Enver Pasha seethed: “My heart is bleeding … our hatred is intensifying: revenge, revenge, revenge, there is nothing else.”

See the previous installment or all entries.