Erik Sass is covering the events of the war exactly 100 years after they happened. This is the 291st installment in the series.

October 24-27, 1917: Disaster At Caporetto

In the spring and summer of 1917, the momentum of events in the First World War seemed to favor the Allies. The U.S. and Greece joined the war, a democratic revolution promised to revive Russia, and the British put the Germans on the defensive again at Passchendaele in Flanders. Just a few months later, however, the tables had turned in dramatic fashion: although American troops began arriving in relatively modest numbers, the British Flanders offensive was flailing in the autumn mud and Russia was teetering on the verge of another (far more radical) revolution.

Then, on October 24-27, 1917, the other shoe dropped. A combined Austro-German force launched a crushing offensive on the Italian front, achieving a successful breakthrough and the near-collapse of the Italian Army. Caporetto is commemorated as one of the worst battlefield defeats suffered by either side during the war, with the virtual destruction of the Italian Second Army ranked alongside debacles like the annihilation of the Russian Second Army at Tannenberg, the collapse of Austria-Hungary’s armies during the Brusilov Offensive of 1916, and the shattering of the British Fifth Army in March 1918 during the final German onslaught. Thanks to Caporetto and the Bolshevik coup in Petrograd, by the end of 1917—after more than three years of war—the fortunes of the Allies had never been at a lower ebb.

Crisis and Complacency

Following the surprise Italian victory at the Sixth Battle of Isonzo, which saw the fall of the town of Gorizia, stasis returned to the front until the Eleventh Battle of the Isonzo in August-September 1917, when the Italians once again managed to push the Habsburg defenders of the First and Second Isonzo Armies back near Montefalcone (though once again the gains came at an astronomical cost in human blood, including 30,000 Italian and 20,000 Habsburg dead).

The Italian conquest of the strategic Bainsizza Plateau during the Eleventh Isonzo threatened to isolate several Habsburg mountain strongholds, endangering Austro-Hungarian control of nearby Tolmein and the Slovenian hinterland to the east. Meanwhile, after 11 bloody battles, the Austro-Hungarian armies on the Isonzo Front were finally stretched to the breaking point. In short, the Central Powers could no longer neglect the Italian front.

At the same time, the Habsburg military had new leadership at the very top. The young, reform-minded Emperor Karl I had succeeded his uncle Franz Josef on the latter’s death on November 21, 1916, and in March 1917 Karl sacked the imperious chief of the Imperial general staff, Conrad von Hötzendorf—one of the main advocates of war with Serbia in 1914, who had frequently butted heads with the empire’s civilian leadership, not to mention his equally imperious German colleagues.

Karl replaced Conrad with General Arz von Straussenberg, who had worked closely with the Germans on the Eastern Front and earned their trust. Straussenberg’s good relations with the German leaders, chief of the general staff Paul von Hindenburg and his own chief of staff, quartermaster general Erich Ludendorff, helped secure seven German divisions from the Eastern Front to bolster the overstretched Austro-Hungarian armies and spearhead a new attack on the Italian Front. The German contribution to the hybrid Austro-German Fourteenth Army, which remained totally under German command, included the elite Alpenkorps, specializing in mountain combat. The Austro-Hungarian Army contributed 10 divisions to the Fourteenth Army, as well as the Austro-Hungarian Second Isonzo Army (previously part of the Fifth Army under Svetovar Boroevic), Tenth Army, and Eleventh Army.

The arrival of 140,000 battle-hardened German assault infantry raised morale among their overtaxed Habsburg allies, and would soon strike fear in the hearts of their foes, according to Ernest Hemingway, whose character Lt. Frederic Henry observes in A Farewell to Arms (based on Hemingway’s own experiences as an ambulance driver on the Italian front): “The word Germans was something to be frightened of. We did not want to have anything to do with the Germans.”

The Germans and Austrians took elaborate precautions to conceal the movement of new troops to the front, as recounted by Erwin Rommel, then a 25-year-old lieutenant whose Württemberg Mountain Battalion, an elite assault unit, would play a major role in the victory:

Because of enemy aerial reconnaissance each prescribed march objective had to be reached before daybreak at which time all men and animals had to be concealed in the most uncomfortable and inadequate accommodations imaginable. These night marches made great demands on the poorly fed troops. My detachment consisted of three mountain companies and a machine gun company, and I usually marched on foot with my staff at the head of the long column.

The Central Powers’ attack at Caporetto would enjoy stunning success in large part thanks to storm trooper units like Rommel’s, using new “infiltration” tactics developed by German Army captain Willy Rohr beginning in the spring of 1915, refined at Verdun in 1916, and recently employed by the German Eighth Army under General Oskar von Hutier at Riga in September 1917.

The new combat technique centered on small, highly trained groups of Stosstruppen (stormtroopers) armed with machine guns, rifles, grenades, mortars, and even field guns, who would penetrate deep behind enemy lines following intense but localized heavy artillery bombardments, in order to neutralize enemy machine guns and artillery before the main infantry assault. The stormtroopers typically bypassed enemy strongpoints whenever possible, leaving them to be surrounded and destroyed by a second wave of larger assault squads with heavy weaponry, and enabling the stormtroopers to keep moving to sow chaos in the rear (below, a German assault platoon rests during the battle).

For his part the Italian chief of the general staff, Luigi Cadorna, ignored repeated warnings of an impending enemy attack, noting the arrival of snow in the Julian Alps and ordering Italian troops to stay on the defensive before going on holiday in Venice in mid-October. Cadorna was confident that the Austrian attack would come 50 miles south of the Isonzo, on the Carso Plateau. Away from headquarters and distracted by growing political opposition to his command in Rome, he also failed to discern that one of his army commanders, General Capello, hadn’t move the Second Army to a defensive footing—leaving a large number of his troops forward deployed on the far (eastern) bank of the Isonzo River, where they could be stranded if the bridges fell. In many areas Italian defenses were discontinuous, with hillside trenches broken by outcroppings, gorges, and other rough terrain—making them perfect targets for infiltration techniques.

Amid heavy autumn rains the Austro-German hammer blow fell at 2 a.m. on October 24, 1917, when artillery unleashed a terrifying bombardment that some German soldiers said exceeded Verdun or the Somme. Even Rommel and his colleagues seemed impressed:

It was a dark and rainy night and in no time a thousand gun muzzles were flashing on both sides of Tolmein. In the enemy territory an uninterrupted bursting and banging thundered and reechoed from the mountains as powerfully as the severest thunderstorm. We saw and heard this tremendous activity with amazement. The Italian searchlights tried vainly to pierce the rain, and the expected enemy interdiction fire of the area around Tolmein did not materialize.

That was probably due in part to the deadly combination of phosgene and chlorine gas shells that overwhelmed Italian soldiers, many of whom failed to put on their gasmasks because the yellow gas blended invisibly into the heavy mountain fog. By dawn Rommel and his assault team, whose mission was to protect the flank of the Bavarian Life Guards in a dangerous mountain assault, were moving forward to their jumping-up points:

A few shells struck on both sides of the long column of files without doing any damage. The column halted close to the front line. We were frozen and soaked to the skin and everyone hoped the jump-off would not be delayed. But the minutes passed slowly. In the last quarter hour before the attack the fire increased to terrific violence. A profusion of bursting shells veiled the hostile positions a few hundred yards ahead of us in vapor and a gray pall of smoke.

At 6 a.m. Italian secondary lines were under fire, and German and Austrian assault groups began appearing in mountain valleys along the Tolmein portion of the Isonzo front, indicating a major assault was under way. However, Italian communications had already been severed by artillery fire in many places, preventing the still-confident Cadorna from learning how serious the situation really was.

After jumping off at 8 a.m., Rommel’s unit passed through the smoldering remains of the Italian front line and swiftly ascended the spoke-like ranges around Mount Mrzli, towering over the Isonzo. On encountering a well-sited Italian strongpoint, Rommel simply moved laterally and continued infiltration techniques over the craggy terrain until he found favorable ground for an attack—using vegetation, outcroppings, and other natural features to shield his troop movements from enemy observation and fire, while platoons provided covering fire for each other as they advanced.

Of course the terrain provided risks of its own. Early in the ascent the Rommel detachment’s armed advance scout, or “point,” accidentally dislodged a small boulder:

At this moment a hundred-pound block of stone tumbled down on top of us. The draw was only 10 feet wide and dodging was difficult and escape impossible. In the fraction of a second it was clear that whoever was hit by the boulder would be pulverized. We all pressed against the left wall of the fold. The rock zigzagged between us and on downhill, without even scratching a single man.

Attracting the attention of large numbers of Italian frontline troops could be fatal, so the stormtroopers focused on enemy units that directly impeded their continuing ascent over the ridgelines. Later in the morning, Rommel used a favorite tactic—deception—to turn a dangerous Italian defensive position protecting an unsuspecting garrison:

I singled out Lance Corporal Kiefner, a veritable giant; gave him eight men, and told him to move down the path as if he and his men were Italians returning from up front, to penetrate into the hostile position and capture the garrison on both sides of the path. There were to do this with a minimum of shooting and hand grenade-throwing … Their rhythmical steps died away and we began to speculate on their success … Again long, anxious minutes passed and we heard nothing but the steady rain on the trees. Then steps approached, and a soldier reported in a low voice: “The Kiefner scouts squad has captured a hostile dugout and taken 17 Italians and a machine gun. The garrison suspects nothing.”

And still Rommel pressed on. After capturing an isolated garrison and taking around 60 prisoners, the German mountain assault team returned to the advance, penetrating deep behind the Italian frontlines:

Our thousand-yard column worked its way forward in the pouring rain, moving from bush to bush, climbing up concealed in hollows and draws, and seizing one position after another. There was no organized resistance and we usually took a hostile position from the rear. Those who did not surrender upon our surprise appearance fled head over heels into the lower woods, leaving their weapons behind. We did not fire on this fleeing enemy for fear of alarming the garrison of positions located still higher up.

Further south, as the Italian defenses collapsed, Caporetto fell to the advancing enemy at 3 p.m., and at 3:30 the retreating Italians blew up the bridge over the Isonzo. However, these defensive measures were belated or irrelevant: the German Fourteenth Army advanced with almost unprecedented speed, and by later afternoon the Germans had occupied the Isonzo Valley while forward units were seizing control of mountain slopes far to the west of Caporetto.

Yet as late as 6 p.m., Cadorna, isolated at his headquarters in Udine, still believed that the attack was a feint to distract from the main enemy offensive on the Carso. Only as October 24 drew to a close did the Italian chief of the general staff grasp the scale of the unfolding disaster, as news arrived that 14 infantry regiments had been pulverized and some 20,000 Italian soldiers taken prisoner, along with ominous reports of mass insubordination and desertion in several divisions.

Over the next three days, from October 25-27, 1917, the Germans brought up artillery and mounted additional attacks to exploit the breakthrough, capturing the plateau around Cividale and threatening Udine itself by October 28—forcing Cadorna and his staff at the Supreme Command to hastily evacuate the town for safer environs to the southwest. Perhaps most spectacularly, Rommel’s 200-man strong assault company scored a legendary battlefield victory on October 25-26, 1917, with the capture of Mount Matajur, the next major peak after Mount Mrzli.

The physical ascent was epic in its own right, and the Germans now faced more determined defenders practiced in mountain warfare. At one point Rommel took characteristically bold action to relieve a surrounded German unit:

The 2d Company held some sections of trench on the northeast slope and was encircled from the west, south, and east by fivefold superiority, an entire Italian reserve battalion … The wide and high Italian obstacles lay in rear of the 2d Company, making retreat to the north slope impossible. The troops defended themselves desperately against the powerful enemy mass; only their unbroken rapid fire prevented an enemy attack. If the enemy ventured to attack in spite of the fire, then the little group would have been crushed … My estimate of the situation was that the 2d Company could be relieved only by a surprise attack by the entire detachment … Under such conditions I believed that the superior combat capabilities of the mountain soldier would prevail.

By the time they conquered Mount Matajur, in two days Rommel’s small force of mountain troops had crossed 18 kilometers of very rough terrain, ascended almost 3000 meters, and captured 9000 Italian prisoners—all at a cost of six dead and 30 wounded.

Meanwhile, the Italian Second Army fell into headlong (though initially orderly) retreat, as described by Hemingway:

The next night the retreat started. We heard that Germans and Austrians had broken through in the north and were coming down the mountain valleys toward Cividale and Udine. The retreat was orderly, wet, and sullen. In the night, going slowly along the crowded roads we passed troops marching under the rain, guns, horses pulling wagons, mules, motor trucks, all moving away from the front.

By October 27 the Second Army under Capello had simply disintegrated, with tens of thousands of beaten, demoralized soldiers streaming towards the rear in pouring rain; the collapse in turn exposed the northern flank of the neighboring Third Army under the Duke d’Aosta, forcing the latter to fall back from Montefalcone before the Habsburg Second Isonzo Army. Within a few weeks Boroevic’s force would advance west to within sight of the lagoons of Venice, now facing the threat that so recently menaced its sister city, Trieste. Will Irwin, an American war correspondent touring the Italian front, described the worried reaction as news of the debacle arrived in Venice:

I was aware that a curious change had come over the appearance of the crowds. Ten minutes before they had been streaming across the plaza. Now there was no movement. They had congealed into groups, talking low and seriously … All that Italy had gained so splendidly in the August offensive gone in one stroke! If it would only stop there!

Elsewhere the Habsburg Tenth Army under Krobatin and Eleventh Army under Conrad (the former Austrian chief of staff, now with a field command) rumbled into action, brushing aside the thin Italian covering force in the Carnic Alps and forcing back the Italian Fourth Army under Giardino—the latter imperiled by the Austro-German advance towards its supply lines. Only the Italian First Army under Giraldi, at the extreme west of the Italian front by Lake Garda, was able to stabilize its position after Conrad’s advance around the Asiago Plateau (the situation was worsened by the decision to dissolve the Italian Fifth Army, a reserve force, in July 1916; below, a retreating Italian 305-millimeter howitzer).

And still the retreat continued amid chaotic conditions well into November, with thousands of Italian troops mixed up with civilians, constantly threatened by the lightning-fast German advance. Hemingway’s narrator Frederic Henry noted: “We were very close to Germans twice in the rain but they did not see us… I had not realized how gigantic the retreat was. The whole country was moving, as well as the army. We walked all night, making better time than the vehicles.”

“I Cannot See When or Where the Awful War Is Going to End”

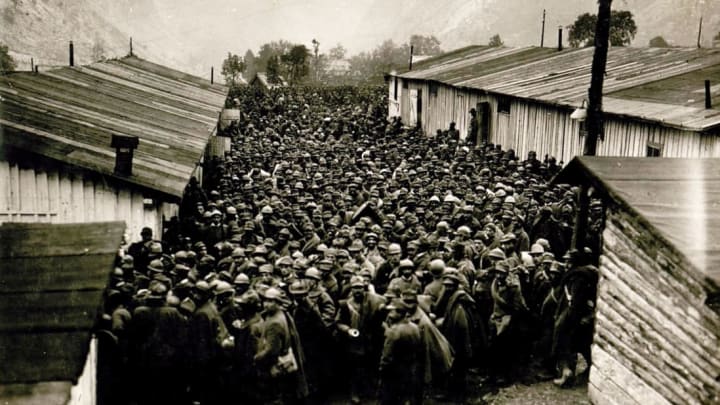

By the time the Italian retreat finally ended on November 12, as the battered First, Third and Fourth Armies took up strong defensive positions behind the Piave River, Italy had lost most of the country’s northeast, exposing Venice to the enemy, at a cost of 305,000 casualties, including 10,000 dead and 265,000 taken prisoner (top, Italian prisoners of war crammed in an Austrian prison camp; below Italian lancers joining the reforming line at the Piave). By contrast the German and Austrian attacking forces suffered just 70,000 casualties, including killed and wounded. The victory also allowed the Central Powers to defend a much shorter line, running via the Asiago Plateau, Mount Grappa, and the valley of the Piave—helping ease a severe manpower shortage by freeing up German and Austrian troops for service elsewhere.

The severity of the defeat at Caporetto triggered a harsh reaction from Cadorna, who realized that he would be held responsible and swiftly placed the blame on the Second Army, openly accusing officers and ordinary soldiers alike of defeatism and cowardice. In fact morale had been at rock-bottom even before the German attack, and during the chaotic retreat thousands of Italian soldiers deserted, while tens of thousands more surrendered without a fight.

Reports of mutiny and mass desertion prompted arbitrary, draconian measures, including the execution of hundreds of soldiers by drumhead tribunals behind the lines. In A Farewell to Arms, Frederic Henry witnesses the execution of an officer who was separated from his troops during the retreat:

"Have you ever been in a retreat?” the lieutenant-colonel asked. “Italy should never retreat.” We stood there in the rain and listened to this. We were facing the officers and the prisoners stood in front and a little to one side of us. “If you are going to shoot me,” the lieutenant-colonel said, “please shoot me at once without further questioning. The questioning is stupid.” He made the sign of the cross. The officers spoke together. One wrote something on a pad of paper. “Abandoned his troops, ordered to be shot,” he said. Two carabinieri took the lieutenant-colonel to the river bank. He walked in the rain, an old man with his hat off, a carabinieri on either side. I did not watch them shoot him but I heard the shots.

Henry narrowly escapes execution himself by throwing himself in the fast-flowing river, swollen with rain. Unsurprisingly he decides to desert: “It was no point of honor. I was not against them. I was through. I wished them all the luck. There were the good ones, and the brave ones, and the calm ones and the sensible ones, and they deserved it. But it was not my show any more.”

The debacle at Caporetto had a devastating impact on Allied morale, leaving little doubt that Britain and France would have to send reinforcements to shore up the Italian front (probably forcing them to call off the Passchendaele offensive). Many ordinary people felt the defeat personally. Charles Biddle, an American pilot volunteering in the Escadrille Lafayette in France, wrote home as the scale of the disaster became known:

What do you all think at home of the recent Hun invasion of Italy? The outlook is pretty gloomy, is it not, but I hope it may serve to make people in America realize that this war is not won yet by a long sight, and that if it is going to be won they have to got to get into it for all they are worth. We certainly should do our utmost without complaining when one considers what a soft time of it we have had so far.

Clare Gass, an American woman volunteering as a nurse in France, noted simply in her diary on October 29, 1917: “The news that Italy has lost thousands of men & hundreds of guns to the Austrians is very startling, I cannot see when or where the awful war is going to end.”

See the previous installment or all entries.