The First World War was an unprecedented catastrophe that killed millions and set the continent of Europe on the path to further calamity two decades later. But it didn’t come out of nowhere. With the centennial of the outbreak of hostilities coming up in 2014, Erik Sass will be looking back at the lead-up to the war, when seemingly minor moments of friction accumulated until the situation was ready to explode. He'll be covering those events 100 years after they occurred. This is the 65th installment in the series.

April 23, 1913: Montenegro Takes Scutari, Austria-Hungary Threatens War

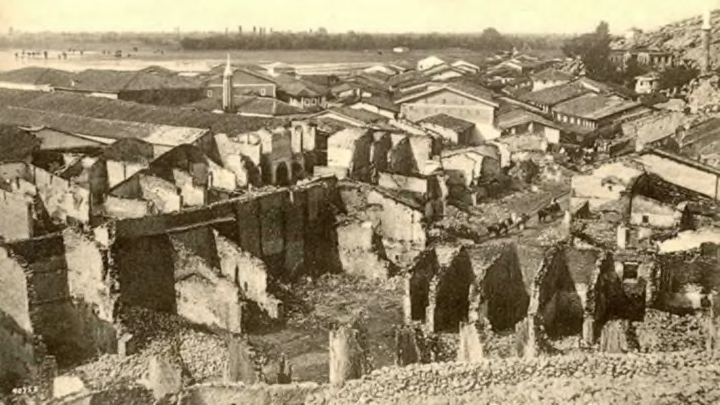

By April 1913, Scutari (Shkodër) had been under siege by the armies of Montenegro and Serbia for six long months. Over the course of the First Balkan War, the Turkish garrison held out against multiple attempts to storm the city, not to mention a barrage of 36,000 shells which inflicted considerable damage (pictured above); meanwhile the European Great Powers, meeting at the Conference of London, agreed to Austria-Hungary’s demand that Scutari should be part of the new, independent state of Albania. To make their message crystal clear, the Great Powers sent a multinational fleet to the Adriatic Sea to blockade Montenegro, and the British admiral in charge went ashore to warn the Montenegrins and Serbians to withdraw or face bombardment. In mid-April, the Serbians bowed to this pressure and withdrew from the siege of Scutari, then joined Bulgaria and Greece in reopening peace negotiations with Turkey—leaving tiny Montenegro alone in its defiance of Europe.

Without Serbian artillery and reinforcements, there was little chance of the Montenegrins storming Scutari under their own power—but in the Balkans there were always other options. On April 23, 1913, the Albanian-Turkish commander of the defending force, Essad Pasha Toptani (who may have been responsible for the assassination of the previous commander, Hasan Riza Pasha, in January) agreed to surrender the city to Montenegro in return for support for his own claim to the throne of the newly-minted kingdom of Albania, plus a suitable sum of cash. In gratitude for this treachery, Montenegro’s King Nikola allowed Toptani to leave Scutari with his sword—a key point of honor—and all his troops.

Although their subterfuge was successful, it’s not clear what the Montenegrins hoped to achieve in the long term, as the Great Powers—including Montenegro’s patron Russia—had agreed that Scutari would go to Albania. Nonetheless, their underhanded conquest of the city triggered another flare up in the Balkan crisis. Having failed to prevent Serbian and Montenegrin expansion in the First Balkan War, Austria-Hungary couldn’t sustain any more insults to its prestige, and the war party, led by chief of staff Conrad von Hötzendorf, was growing stronger. On March 20, 1913, the German ambassador to Vienna told Berlin that Berchtold was viewed with contempt by Austrian officialdom for his vacillating foreign policy. Pressure was building on the indecisive foreign minister to demonstrate Austria-Hungary’s strength and determination to withstand the rise of Slavic nationalism in the Balkans.

Sensitive to this criticism—and perhaps realizing for the first time just how dire the dual monarchy’s situation was—Berchtold suddenly swung towards the hawks, adopting a far more aggressive stance towards Austria-Hungary’s Slavic neighbors. On April 29, Austria-Hungary began massing troops near the Montenegrin border, and on May 2, the Austro-Hungarian joint council of ministers approved Berchtold’s proposal to undertake military action against Montenegro if necessary, with Conrad demanding outright annexation of the troublemaking kingdom. At the Conference of London, Austria-Hungary demanded a bombardment of Montenegrin positions by the multinational fleet, and threatened to act unilaterally if the other Great Powers refused. Germany expressed support for military intervention, and on April 30 the French ambassador to Berlin, Jules Cambon, relayed a German warning to Paris that Germany would stand beside Austria-Hungary if the latter were attacked by Russia. The prospect of a general European war was rearing its head once again, and once again the other Great Powers—France, Britain, and Italy—were sent scrambling to prevent disaster.

See the previous installment or all entries.