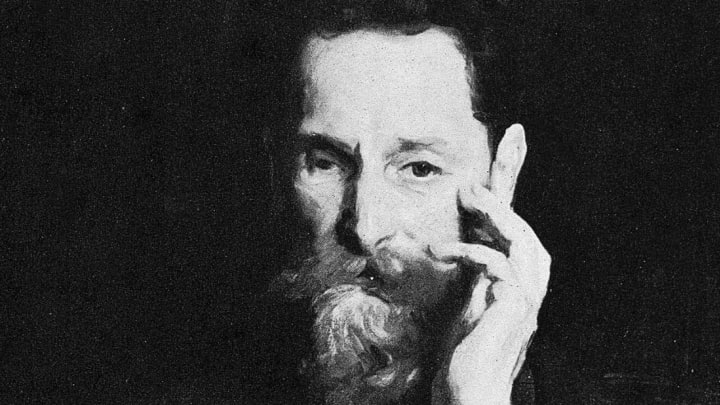

The Pulitzer Prize has long been an object of desire for writers, photographers, cartoonists, and even some musicians. But many of them know little or nothing about Hungarian native Joseph Pulitzer, for whom the prize is named. The Pulitzer name didn’t always have so much clout—in fact, as a young immigrant, Pulitzer found himself in a series of dead-end gigs, and was even homeless at times.

In honor of the 100th anniversary of the first Pulitzer Prizes—first awarded June 4, 1917—here are 12 facts about the man whose name now evokes the highest distinction.

1. HE WAS REJECTED BY SEVERAL ARMIES.

As a teenager, Joseph Pulitzer was turned down by Austrian, British, and French armies because of his poor eyesight. But the U.S. Civil War was then in full swing, and a Union army recruiter approached Pulitzer about enlisting as a substitute for a draftee. Pulitzer arrived in America in September 1864 by way of Boston Harbor, but reportedly dove into the harbor as his ship approached land in an effort to keep the enlistment bounty. He made his way to New York, where he enlisted on his own behalf, thereby keeping the enlistment bounty instead of letting it go to the agent. He briefly served in a Union cavalry unit, and was honorably discharged at the Civil War’s end.

2. HIS FIRST U.S. YEARS WERE HARDSCRABBLE.

After the war, the young and nearly penniless veteran was unable to make it in New York—where he slept on park benches—and headed for St. Louis, Missouri. Arriving by train in East St. Louis, Illinois, he was too broke to pay his way across the Mississippi River, so he shoveled coal on a ferry in exchange for free passage. Upon reaching St. Louis, he waited tables, tended to mules, and—in a clear sign of desperation—worked as a gravedigger during an 1866 cholera epidemic.

3. HIS FIRST BIG CAREER OPPORTUNITY CAME THANKS TO CHESS.

While observing a chess match between two German speakers at a St. Louis library, Pulitzer critiqued a move. Though some chess players might take offense, these two—who worked as editors at the area’s main German-language newspaper—took an interest in the sharp young Pulitzer. He soon was working with them as a reporter at the Westliche Post, where he later became a part-owner.

4. HE ALSO HAD A POLITICAL CAREER.

Many prominent newsmen have identified with a political party, but Pulitzer took it a step further, actually serving as a politician. He worked in the Missouri state legislature, and later as a Congressional representative from New York’s 9th district. He also served as a delegate for the Liberal Republican Party in 1872 and for the Democratic Party in 1880.

5. HE COMMUNICATED IN SECRET CODE.

After eventually owning such major outlets as the New York World, and endlessly striving to expose high-level corruption, Pulitzer made rivals and enemies in high places. In order to encrypt his communications, he devised a code for speaking with his editors, attorneys, and family that consisted of some 20,000 names and terms. Examples included “Andes” (himself), “Glutinous” (Theodore Roosevelt), “Malaria” (The Republican Party), and “Geranium” (the New York Journal).

6. HE SHOT SOMEONE.

While in political office, he made enemies with a building contractor. On January 27, 1870, they argued at a hotel in Jefferson City, Missouri. After being called a liar, Pulitzer went to get his old army pistol. He then returned to the hotel and demanded an apology, but was punched instead. So he produced his pistol and shot the contractor in the leg. Though his victim survived, had the incident occurred today Pulitzer would likely face serious jail time and the destruction of his journalistic and political careers. Instead, he was only fined heavily, but managed to retain his political position, though he did lose the ensuing election.

7. HE HAD A THING FOR THE NUMBER 10.

Pulitzer, who was born on the 10th of April and reportedly gained control of both the Saint-Louis Evening Dispatch and the New York World on the 10th of the month, often refused to “do any important thing” until the 10th day of any given month. But when his Manhattan residence of 10 East 55th Street burned down in 1900, he moved to 11 East 73rd Street.

8. HE WENT BLIND.

The publishing mogul who brought printed stories to countless millions lost his eyesight, and did so at the young age of 40. Though he maintained his newspaper enterprise with assistance, his blindness exacerbated lingering mental conditions. He became increasingly reclusive and also suffered a nervous breakdown.

9. EVEN AFTER GOING BLIND, HE WAS AN ART ENTHUSIAST.

A 1909 magazine profile describes Pulitzer as surrounded by a “splendid and costly” art collection “he cannot see.” Connoisseurship would run in the family, as grandson Joseph Pulitzer III, himself a publishing mogul, would acquire one of the world’s most sterling modern art collections before his death in 1993.

10. HE BECAME VERY, VERY SENSITIVE TO NOISE.

For such a media dynamo, he certainly valued his quiet time, especially as his somatic and psychological troubles grew more severe. He even soundproofed the bedroom of his Manhattan residence along with his yacht, and his vacation estate in Bar Harbor, Maine was dubbed the “Tower of Silence.”

11. HIS BROTHER WAS ALSO A NEW YORK NEWSPAPERMAN.

Pulitzer’s younger brother Albert also immigrated to the U.S., and in 1882, he founded the New York Morning Journal, a one-cent daily paper. The brothers, both running competing Gotham publications, reportedly became bitter rivals. Albert Pulitzer would sell his paper to William Randolph Hearst (his brother’s arch-rival) and ultimately committed suicide in Vienna, Austria, in 1909. Though the brothers had been estranged, the surviving Pulitzer spent $15,000 to give him a fitting farewell and burial.

12. HIS LAST WORDS WERE IN GERMAN.

At age 64, Joseph Pulitzer died of heart failure on October 29, 1911, while on board his yacht in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. Right before his death his German secretary was reading to him a narrative about the French King Louis XI, and just as she reached the part about the monarch’s death, the ailing Pulitzer said, “Leise, ganz leise, ganz leise”—“Silently, very quietly, very quietly”—an instruction to lower her voice.