The First World War was an unprecedented catastrophe that killed millions and set the continent of Europe on the path to further calamity two decades later. But it didn’t come out of nowhere. With the centennial of the outbreak of hostilities coming up in 2014, Erik Sass will be looking back at the lead-up to the war, when seemingly minor moments of friction accumulated until the situation was ready to explode. He'll be covering those events 100 years after they occurred. This is the 61st installment in the series. (See all entries here.)

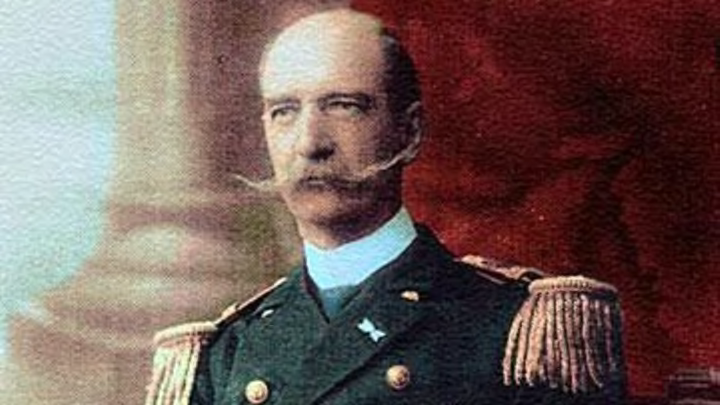

March 18, 1913: King George I of Greece Assassinated

The Greek conquest of Salonika on November 9, 1912 was a major historical event by any standard. Founded in 315 BCE and captured by the Ottoman Turks in 1430 CE, Salonika (Greek: Thessaloniki) was a crown jewel of the Balkans and the main prize of the First Balkan War. Thus it was a foregone conclusion that King George I of Greece would pay a triumphal visit to glory in his conquest (and cement Greek ownership of the city, which was also claimed by Greece’s ally Bulgaria).

In the afternoon of March 18, 1913, the king was taking his daily walk along the waterfront near the “White Tower,” a famous fortress built by the Ottomans in the 16th century. The king’s advisors had warned him that the mood in the city was unsettled, but George—perhaps trying to demonstrate the common touch for which he was famous—had insisted on taking his stroll without bodyguards. So there was no one to protect the king when, around 5:15 p.m., an anarchist named Alexandros Schinas slipped out of a café, walked up behind him and shot him several times in the back at point-blank range. One of the bullets pierced the king’s heart, killing him instantly.

Like so many other successful assassins, Schinas’ momentous crime dwarfed his modest achievements in life up to that point. Some years before he’d joined the Eastern European exodus to America, where he worked for a time in the kitchen of New York City’s Fifth Avenue Hotel; co-workers recalled his passionate rants against privilege and authority. Failing to make a life for himself as an immigrant in the New World, Schinas returned to his hometown in Greece, where he founded an anarchist school that was quickly shut down by the authorities. At the time of his arrest, the Greek police described Schinas as a homeless alcoholic. On May 6, 1913, he died after “falling” from a police station window; the death was officially recorded as a suicide, though there is obvious reason for doubt.

The assassination came just a few weeks before the 50th anniversary of George’s accession to the throne. Ironically, after his Golden Jubilee celebration the 67-year-old monarch was planning to abdicate in favor of Crown Prince Constantine. Now, as the old king’s body lay in state in Salonika, the new king took the constitutional oath of office in a subdued ceremony in front of the Greek chamber of deputies in Athens on March 21, 1913. In contrast to the somber mood inside parliament, in the surrounding streets large crowds cheered the new king, who’d captured the popular imagination with his victories in the First Balkan War.

As a young man Constantine had spent a number of years in Germany, where he studied at universities in Leipzig and Heidelberg, and became friends with Kaiser Wilhelm II; in fact in 1889 he married Wilhelm’s sister Sophia. During the coming Great War his German sympathies would put Constantine at odds with the British and French, who helped establish a rival government under Prime Minister Venizelos in Salonika. In 1917, the Allies forced Constantine to abdicate in favor of his son Alexander, who then brought Greece into the war on the side of the Allies.

Sadly political assassinations were all too common during this period, due in part to the spread of violent anarchism, a shadowy international movement which advocated “propaganda of the deed”—terrorism—and posed a threat similar to Islamist extremism today. Anarchist terrorists favored high-profile targets: On September 14, 1911, Russian prime minister Pyotr Stolypin was murdered in front of Nicholas II and his family by the anarchist Dmitri Bogrov; on November 12, 1912, Spanish prime minister José Canales y Méndez was assassinated by the anarchist Manuel Pardiñas; and on April 13, 1913, anarchist Rafael Sancho Alegre tried and failed to kill Spanish King Alfonso XIII.

Of course anarchists weren’t solely responsible for the rash of assassinations: Then, as now, there were also plenty of well-armed lunatics in circulation. On October 14, 1912, a psychotic saloonkeeper named John Schrank was barely foiled in his attempt to kill Teddy Roosevelt at a campaign stop in Milwaukee. Lunacy and ideology often overlapped: Leon Czolgosz, the anarchist who murdered President William McKinley at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York in 1901, was clearly mentally disturbed.

As might be expected, many assassinations took place as part of coups and political upheavals. In the Ottoman Empire, war minister Nazim Pasha was killed by the Young Turks during the coup on January 23, 1913, and Grand Vizier Mahmut Sevket Pasha was assassinated by military officers angry about Turkish defeats on June 11, 1913. In Mexico, President Francisco Madero and Vice-President José María Pino Suárez were murdered by coup plotters on February 22, 1913. And in China Song Jiaoren, a founder of the Kuomintang, was assassinated on March 20, 1913, probably at the behest of rival Yuan Shikai.

Another prominent cause of political violence during this period was nationalism—and nowhere was more seriously afflicted than Austria-Hungary, a dynastic empire whose multinational composition was particularly ill-suited to the modern era. Here nationalism mixed with anarchism to produce an especially dangerous brew—and fire-breathing Slavic nationalists in neighboring Serbia were eagerly stirring the pot, hoping to liberate their ethnic kinsmen in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Click to enlarge.

On June 15, 1910, a Slavic nationalist and anarchist named Bogdan Zerajic made an unsuccessful attempt on the life of General Marián Varešanin, the Hungarian military governor of Bosnia-Herzegovina; Zerajic killed himself and was venerated as a heroic martyr by Slavic nationalists. On June 7, 1912, a Hungarian nationalist named Gyula Kovács tried and failed to kill the Hungarian speaker of the house, István Tisza, whom he accused of collaboration with Hungary’s Austrian oppressors. A day later, on June 8, 1912, the ban (imperial governor) of Croatia, Slavko Cuvaj, barely escaped assassination by a Bosnian Croat, Luka Jukić, who managed to kill several other officials. On August 18, 1913, Stjepan Dojčić, a Croatian house painter who had emigrated to America and then returned, failed in his attempt to assassinate Iván Skerlecz, Cuvaj’s successor as governor of Croatia. And on May 20, 1914, a second plot against Skerlecz’s life was foiled by police in the nick of time; a “Yugoslav” nationalist, Jacob Schafer, was arrested, and the investigation soon traced the plot back to Serbia.

Back in February 1912, Jukić (who would try to kill the Croatian governor in June of that year) had helped organize nationalist protests by students in Sarajevo, the provincial capital of Bosnia-Herzegovina, together with a fellow Bosnian Serb named Gavrilo Princip; Princip—a small, wiry 17-year-old with intense blue eyes—had threatened students who didn’t want to participate in the protests with brass knuckles. In March 1913, Princip, now 18 years old, arrived in the Serbian capital Belgrade, supposedly to attend high school. Here he would come into contact with a secret Serbian nationalist group called “Unity or Death”—better known as “The Black Hand.”

See previous installment, next installment, or all entries.