The First World War was an unprecedented catastrophe that killed millions and set the continent of Europe on the path to further calamity two decades later. But it didn’t come out of nowhere. With the centennial of the outbreak of hostilities coming up in 2014, Erik Sass will be looking back at the lead-up to the war, when seemingly minor moments of friction accumulated until the situation was ready to explode. He'll be covering those events 100 years after they occurred. This is the 60th installment in the series. (See all entries here.)

March 11, 1913: Austria-Hungary and Russia Stand Down

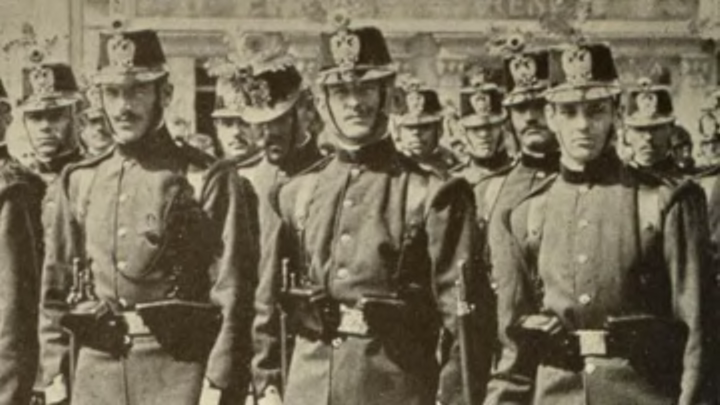

After a four-month-long armed standoff provoked by the First Balkan War, on March 11, 1913, Austria-Hungary and Russia reached an agreement for both sides to stand down, defusing a dangerous situation threatening a much broader war. The Austro-Hungarian armies in the northeastern province of Galicia would de-mobilize, and Russia would allow the senior conscript class to go home, lowering Russian strength to normal peacetime levels.

Coming on the heels of Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Josef’s personal intervention with the Hohenlohe Mission in February, the decision for mutual “de-escalation” was a major diplomatic breakthrough. In terms of the Balkan crisis, it sent a strong signal to Serbia and Montenegro that Russia wasn’t going to back Serbia’s ambitions to gain access to the sea at Durazzo (Durrës), or Montenegro’s ambition to take the important city of Scutari (Shkodër). As part of the settlement, Russia agreed that both cities would be included in the new independent Albania, as previously demanded by Austria-Hungary; in return Austria-Hungary agreed to give the inland market towns of Dibra (Debar) and Jakova (Dakovica) to Serbia as consolation prizes.

On the surface, the agreement held out hope for lasting European peace—but it failed to resolve the underlying tensions pushing the continent towards war, and may even have contributed to them.

Although Austro-Hungarian foreign minister Count Berchtold appeared to score a diplomatic victory with the creation of an independent Albania, he was still roundly criticized by hawks in Vienna for allowing Serbia’s rise: having almost doubled its territory and population at the expense of the Ottoman Empire during the First Balkan War, the Slavic kingdom looked more threatening than ever to Austro-Hungarian officials, who feared (correctly) that the Serbs hoped to liberate the Empire’s restive Slavic peoples next. At the same time, the apparent success of Austria-Hungary’s intimidation tactics left Berchtold with the mistaken impression that Russia wouldn’t back up Serbia with military force, leading him to adopt a more aggressive stance in future conflicts. In a little over a year, all these factors would converge to produce disaster.

Germany and Britain Settle Colonial Boundaries

While Austria-Hungary and Russia ironed out their differences in the Balkans, Germany and Britain also appeared to be mending fences with the first of several agreements settling colonial disputes in Africa.

With a presence in West Africa dating back to the 17th century, Britain began taking formal possession of colonies including the Gold Coast (incorporating the former Ashanti Empire) and Nigeria in the latter half of the 19th century. Germany, a relative newcomer to the colonial game, received the nearby colonies of Togo and Cameroon as part of the European division of Africa at the Conference of Berlin in 1884. France ceded additional territory to German Cameroon to help resolve the Second Moroccan Crisis in 1911.

Because geographical boundaries were originally based on agreements with local tribes (who didn’t think of sovereignty in terms of lines on a map) the border between German Cameroon and British Nigeria remained hazy until 1913, when German diplomats—hoping to further bolster good relations established at the Conference of London—approached their British counterparts about a compromise. With the Anglo-German Agreement of March 11, 1913, the two powers drew a definite border from Yola, in what is now Nigeria, to the Gulf of Guinea, some 500 miles to the southwest (well, fairly definite: Nigeria and Cameroon still dispute ownership of the Bakassi Peninsula, which was assigned to Cameroon in 2002 by the International Court of Justice, citing the Anglo-German Agreement).

As noted, this was just one of a series of colonial agreements between Britain and Germany, which later included a secret treaty dividing up Portuguese colonies in Africa and a diplomatic agreement over the controversial Berlin-to-Baghdad railroad. All these treaties and conventions raised hopes in Germany that relations with Britain were finally on the mend—and this, in turn, led the Germans to hope Britain would stay out of a war between Germany and France.

This interpretation was, like the rest of Germany’s foreign policy, unreasonably optimistic. True, the British were genuinely interested in resolving colonial disputes—after all, it seemed foolish to allow minor disagreements about faraway places to threaten the stability of the international order. But the whole point was to keep the peace closer to home: The balance of power in Europe was far more important to Britain than practically any colonial issue. Indeed, the British Empire wouldn’t mean much if Britain itself were under the thumb of a continental conqueror.

See previous installment, next installment, or all entries.