The surge in affordable 3D printing in recent years has allowed hobbyists to craft everything from customized toys to hair to prosthetic duck feet, with the only limit being the creator's imagination. Now, researchers in Germany are close to achieving a technique that could revolutionize both 3D applications and glassmaking by giving us the power to 3D print glass.

In a study published in Nature this week, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) investigator Dr. Bastian Rapp presented a way of manufacturing a “liquid glass” that can be manipulated with 3D printing software and then heated until it’s a useful solid. (Normal glass consists of melted sand made from sheets in molten tin vats.) By making the glass dispensable through 3D printing nozzles, Rapp believes we’ll soon be able to 3D print glass that’s of sufficient quality for lenses, mirrors, and even drinking cups.

Previous attempts to conceive of a new way of glass production via 3D printers haven’t resulted in glass smooth enough for widespread use, according to The New York Times. Rapp’s method, called stereolithography, uses glass nanoparticles and suspends them in a liquid that hardens under UV light. As the printer shapes whatever design the software calls for, the light turns the liquid into a solid; a final step in a heated oven further solidifies the glass and burns off any excess materials.

The end result is said to be identical to commercial silica glass. It’s expected that the process could make glass as prolific an element in 3D printing as plastic.

The glass is also clear enough that its potential uses include the kind of fine glass needed for commercial applications like smartphone lenses or computing-based components. And because software is able to create these elaborate designs and shapes, as opposed to time-consuming human effort, observers believe it will be substantially cheaper.

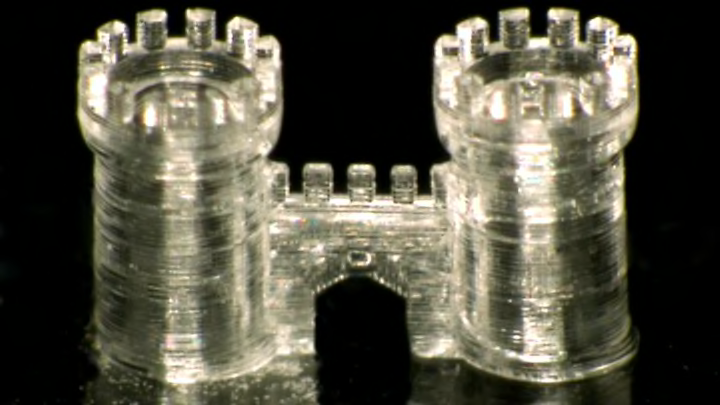

As part of their proof of concept, KIT ran off tiny glass pretzels, a honeycomb, and miniature castles to demonstrate the level of detail available with the technology. In normal glassmaking, acids and chemicals are typically needed to etch designs and shapes.

KIT asserts that this type of 3D printed glass doesn’t require specialized equipment and is feasible with conventional printers, though it will probably be some time before the technology becomes widely used. When it does, the applications will likely go well beyond expensive technology production; Dr. Rapp envisions a day when dropped glasses or smashed flower vases will be easily replaced with a quick 3D solution.