If it wasn’t for the fact that he and his wife had a baby on the way, Brian Kalt may never have discovered how to commit the perfect crime.

An untenured law professor at Michigan State University in 2004, Kalt needed to publish one article annually in order to stay on track professionally and remain eligible to receive summer pay. He began researching the Sixth Amendment of the Constitution, which stipulates that jurors in federal criminal trials must live in both the federal judicial district and the state where a crime was thought to be committed. His original idea had been to examine how some states allowed for a trial in one of two neighboring counties depending on how close the criminal act was to the dividing line: It’s a small but pivotal loophole that gives some prosecutors the unusual choice of being able to pick a location more receptive to their case.

Kalt kept seeing repeated reference to the fact that district boundaries typically followed state lines, with one exception: the District of Wyoming. Time and again, the authors would indicate that it was of little significance. But Kalt was curious. What was different about Wyoming? And was it really so insignificant?

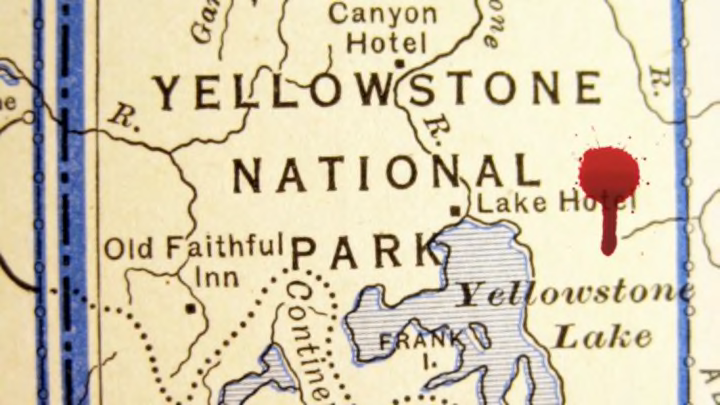

With limited time to write a paper before his baby arrived and diverted all his attention, Kalt decided to postpone his more involved initial idea and pursue the second. After more research, he discovered that Wyoming’s district geography was unique among the 50 states. As a result of some sloppy Congressional maneuvering, there exists a 50-square-mile zone in Yellowstone National Park where someone could—hypothetically—commit a crime and get away with it. Including murder.

Kalt knew what his legal theory paper was going to be about.

“I like to say that there are two kinds of people who sit around thinking about how to get away with murder,” Kalt tells Mental Floss. “Psychopaths, and then neurotic people who are afraid of psychopaths.”

Kalt is in the latter category. The scenario he presented in his 2005 paper, “The Perfect Crime” [PDF], was written as a cautionary tale, not an instructional manual. The theory goes like this: Yellowstone, a federally-supervised national park that resides mainly in Wyoming, has small patches of land bleeding into neighboring Idaho and Montana. Together, both make up roughly 9 percent of the park; the Idaho portion is uninhabited land with few visitors. But because the entire park falls under the District Court in the District of Wyoming, that means anyone in that area who commits a crime would be doing so both in the state of Idaho and the District of Wyoming.

This is where a federal prosecuting attorney’s head would begin to throb. (And it would be a federal case: Yellowstone is under exclusive federal jurisdiction.) The Sixth Amendment instructs that a federal jury must be assembled from both the district and state in which the crime was committed. In order for that to work for that particular area of Yellowstone, there would have to be residents—and there aren’t. You can’t form a jury from anywhere else in Idaho because they’re not in the District of Wyoming; likewise, the District of Wyoming has no Idaho residents. (The Montana portion has a few dozen, though it would still be problematic to get a full panel of 12 jurors.) And you can’t hold a trial in Wyoming because Article III of the Constitution insists that it take place in the state where the offense occurred.

No court could assemble a jury from an empty jury pool. With no jury, there’s no trial. No change of venue in a federal criminal trial is possible unless the defendant requests it. And someone who decides to strangle someone else in what Kalt dubbed “the Zone of Death” stands a better-than-fair chance of going free as a result.

“The trial judge could probably find a way to convict the person,” Kalt speculates. “The prosecutor would look at my theory and say the purpose of the provision is to let communities govern themselves, not to follow pointless formalities and let a killer go free. But the defense could say that the constitutional text is perfectly clear as written and must be followed.

"It would get appealed up to the 10th Circuit or the Supreme Court. They might allow the prosecution to go forward, but they might agree with me that we just can’t pretend the Sixth Amendment isn’t there and that there is no excuse for Congress not to pass a simple fix.”

If the Constitution is respected, the murderer would walk.

There are qualifiers, though: If someone violated weapons laws outside the state, or was somehow proven to have conspired to commit a murder, they’d be on the hook in whichever district those offenses were committed. But if two hikers took a stroll and one snapped, smashing the other with a rock, it would be a geographically self-contained crime, and probably as close to a perfect murder as any psychopath could hope to achieve.

Kalt felt this made for a fine—if morbid—legal quandary, and one he could fully analyze before his wife gave birth. But he also feared that it could incite someone with malicious intent to potentially take a risk and try to commit homicide without consequences. Before publication, he attempted to get the attention of Congress and the Department of Justice to see if the loophole could be closed. He wrote to senators and congressmen—more than two dozen people in all.

He was almost totally ignored. “They didn’t even acknowledge the correspondence,” he says. But once the article came out, NPR and the National Enquirer came calling; a novelist, C.J. Box, wrote a suspense thriller, Free Fire, based on the premise. The latter caught the attention of Wyoming senator Mike Enzi, who was a fan of Box’s book series and reached out to Kalt. After some promising exchanges, nothing happened there, either. As of 2021, no action has been taken to try and sew up this rather morbid legal quagmire.

Although Kalt understands that the government doesn't usually take action against hypothetical threats, he has no idea why there is no interest in addressing it. The simple solution, he says, would be simply to pass a law redrawing the District of Wyoming to include just Wyoming, and the District of Idaho to include all of Idaho.

No one has taken the initiative. Many who read his theory, both legal and layperson, shrug and say a judge just wouldn’t let a killer go free.

This rationalization bugs Kalt. “That’s not a legal argument,” he says. “Tell me how the Sixth Amendment wouldn’t apply.”

Before he wrote a follow-up paper in 2007 [PDF], Kalt got wind of a case that had the potential to finally address the issue once and for all. It involved a killing in Yellowstone territory—and just as he had feared, the accused invoked Kalt’s legal argument as a defense.

In December 2005, shortly after the publication of Kalt’s first paper, a man named Michael Belderrain took aim and shot an elk while standing in the Montana section of Yellowstone (although the elk itself was just outside park boundaries). But because he fired from within the park and dragged the elk’s head through the park, the crime was deemed to have occurred in Yellowstone and Belderrain was brought up on charges in the District of Wyoming hundreds of miles away in Cheyenne.

But Belderrain and attorneys argued that it would be unconstitutional to try him in Wyoming when the crime was committed in Montana. If a judge declared he’d be tried in Wyoming anyway while referencing Kalt’s theory, it might have motivated Congress to resolve the issue.

Instead, the judge circumvented the whole matter, rejecting the “esoteric” notion put forth by Kalt and ordering Belderrain to stand trial in Wyoming without any exploration of the Park’s theoretical no man’s land of unpunishable criminal territory.

“He didn’t say what his interpretation was, or why I was wrong,” Kalt says. “And then the prosecutor conditioned Belderrain's plea deal on him not appealing this issue. They just left it wide open to try in a higher-stakes case.”

This is Kalt’s recurring fear: That even if a murder were to take place in Yellowstone that motivated Congressional action, it wouldn’t be of much use to the dead person. Nor would some of the other prospective ways a prosecutor might deal with a criminal matter in the Zone. The criminal could be charged with a misdemeanor that wouldn’t require a jury, but the sentence would be light; the victim’s family might sue in a civil case, but money is a poor substitute for a human being. Wyoming could also try and hastily assemble a jury pool by moving in residents to that unoccupied area of Yellowstone, but it would be transparent at best, and defense lawyers would have a field day with the implications of a biased panel.

That leaves Kalt’s own work as a possible smoking gun. What if someone were to kill in the Zone, use Kalt’s argument as a defense, and investigators could prove the defendant had read his theory prior to going to Yellowstone to bludgeon someone with a rock?

“They might try it,” Kalt says, “but you’d have to prove that beyond a reasonable doubt. Searching his laptop and seeing he read the article might be pretty good evidence, but they could just say they were aware of it. You can’t prove that’s why they did it. Plenty of people go to that part of the park.”

More than usual, in fact. Kalt says he’s heard there are more visitors to that area of Yellowstone since his article made the rounds. They’re curious, he hopes, and not casing. “It’s hard for me to stop worrying about the possibility,” he says. “Even if it didn’t inspire someone to commit the crime, it might help them go free.

“But I don’t think the blame lies with the person who discovered a problem, wrote something [16] years ago, and has been trying to get it fixed ever since. It would lie with a system that doesn’t take things seriously until it’s too late.”

A version of this story ran in 2016; it has been updated for 2021.