He ran on a platform of ice cream.

On April 8, 1986, Clint Eastwood defeated incumbent Charlotte Townsend to become mayor of Carmel, a small seaside city in his home state of California. With just 4500 residents and one square mile of land, the town was a perfect fit for the actor, who professed no grand ambitions to run for office for anything larger.

But why did Eastwood—at 55, still churning out hit movies more than 30 years after beginning his career as a screen actor—choose to run at all? In 1985, Carmel’s city council gave him what he alleged to be an extraordinary amount of grief over plans to erect office buildings on property he owned within city limits. Eastwood was so aggrieved he sued the council, and won an out-of-court settlement; the settlement allowed for permission to build if he used more wood than glass.

Carmel had long been a city inoculated against any kind of radical development: There weren't even street signs. (All mail went to a central post office.) A 1929 zoning law, which was still in effect, even banned ice cream cones from being sold.

Eastwood felt that residents were divided between a devotion to keeping the area modest and those who felt new business would be economically beneficial. On January 30, 1986—just hours before the deadline—he decided to run for office.

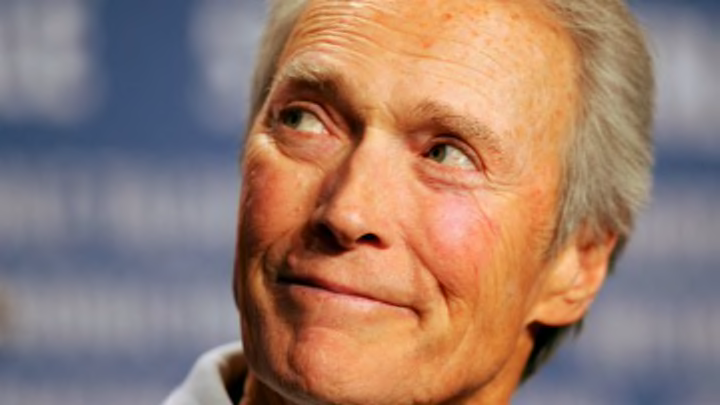

Getty

He called two-term Mayor Townsend a “litigious” official and vowed to ease the tension between factions. While his celebrity as a performer helped, the town also felt indebted to him for rescuing a historic animal sanctuary, the Mission Ranch, from being bulldozed by condo developers. When city officials couldn’t buy it back, Eastwood spent almost $5 million of his own money to keep it standing.

Unable to stir that kind of sentiment, Townsend sniped that Eastwood, who owned a home within city limits, had an unlisted telephone number in the phone directory, whereas she took calls from residents any time. (Eastwood vowed to get an answering machine.)

The day of the election, Eastwood received 2166 votes to Townsend’s 799. He was sworn in the following week. City Hall, a tiny piece of real estate, quickly gave way to a local women’s club that could fit 200 people for his weekly town council meetings. As one of his first acts in office, Eastwood tossed out the planning board that had vetoed an ice cream prohibition repeal; men, women, and children could enjoy cones, and proprietors could sell them.

Despite the landslide victory, not everyone was pleased with Eastwood’s new role. Tourism increased markedly, with fistfights over the few available parking spaces and traffic that choked Ocean Avenue, the main artery in the city. A "Clintsville" gift shop popped up, along with a nearby Hyatt Regency that used the slogan “Make My Stay.” Eastwood, residents said, had attracted "two-hour tourists" to their quiet hamlet.

Getty

Still, Eastwood’s rule proved productive. During his first year in office, he installed more public toilets, added more stairways leading to the beach, and expanded the offerings of the local library. If he was shooting a movie, he’d fly back for the weekly council meetings. Eastwood even penned a regular column in the town’s paper, The Carmel Pine Cone, and used one installment to compare councilman James Wright to a “spoiled child” for not showing up to meetings.

Eastwood did not seek reelection, telling journalists in February 1988 that he felt it was time to devote more attention to his children. The $200 salary he drew every month was donated to a local youth center.