Larry Dewayne Riddick, Jr. had no way of knowing there would someday be an easier way of doing this. In just a few years, pirating feature films for profit—or just for the sake of undermining huge corporations—would be as effortless as clicking a mouse.

But this was 1983. And if Riddick wanted his own personal print of Return of the Jedi to peddle on the black market, he’d have to resort to more crude methods. He’d have to take it by force.

Riddick, 18, stood in the parking lot of the Glenwood Theaters in Overland Park, Kans. and watched as John J. Smith exited the building. Smith was the projectionist; Jedi was finishing its sixth week as the most popular film attraction in the country. It was after midnight. As Smith walked to his car, Riddick came up beside him and flashed a gun. He had come for the movie.

Smith told him roughly 20 people were still inside the theater. Riddick stewed in Smith’s car for 20 minutes, waiting for the last patron to leave. Once inside, he forced Smith to unspool the 70mm film print from the large metal canisters and into a series of portable containers. It took over an hour.

Once the film had been prepared for transport, Riddick fled the scene. In the increasingly sordid and violent world of movie piracy, he had just made off with the equivalent of a king’s ransom. Return of the Jedi, the concluding chapter in the original Star Wars trilogy, was so coveted that a wealthy couple would soon agree to pay $10,000 for the print.

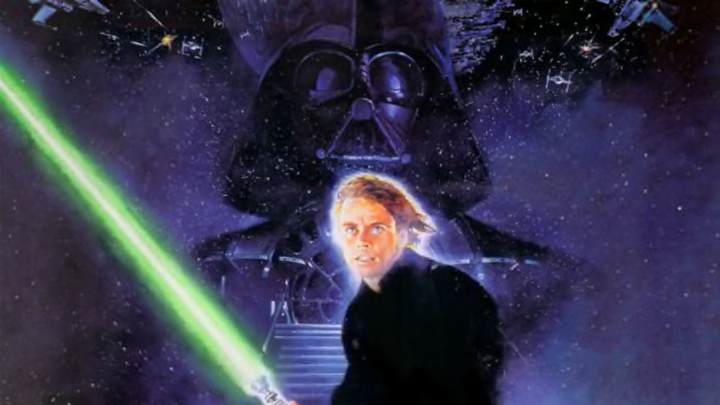

iStock

Screening a film without paying the distributor or exhibitor has existed for practically as long as the movies themselves. Early trade magazines ran ads warning “dupers” of copyright infringement. When the original Star Wars was released in 1977, unauthorized prints were sold for as much as $1000.

The 1980s brought a new dynamic: videocassette players. With videotapes, pirates could duplicate films 100 times over and charge a premium for the lurid privilege of owning a popular feature. Unscrupulous people with disposable income or international clients motivated by delayed foreign release dates were a pirate’s key clientele. Normally, projectionists could be bribed for a few hundred dollars to let a duper “borrow” it and strike copies before returning it. It was collusion, and the only parties being harmed were the studios and theaters.

By the time Return of the Jedi was released in May 1983, VCRs were installed in more than 30 million homes worldwide, with that number expected to grow exponentially in the years ahead. It was a ripe industry for bootlegs, and no film held more temptation than the third and (presumed) final film in the Star Wars franchise.

Return of the Jedi's distributor, 20th Century Fox, knew the movie would become a high-profile target. To dissuade any illegal distribution, the studio circulated word that each print of the film would be marked with a code that would allow them to identify the source of a bootleg. In truth, there was no code; they simply hoped the threat would be enough to keep the movie off the black market.

That didn’t happen. Instead of consorting with theater employees, pirates desperate to profit from Jedi—which could fetch up to $200 for a good-quality copy—decided to utilize direct methods. In addition to the theft in Overland Park, theater employees in Santa Maria, Calif. were confronted by two men wearing clown masks, one wielding a gun. Marched upstairs to the projection room, they were forced to unlock it and hand over the movie. In Columbia, S.C., a print disappeared before a manager arrived for work the morning of May 24, the day before the film's premiere. While the room held several movies, only Jedi was missing.

Fox and Lucasfilm condemned the practice in the media, with Lucasfilm president Robert Greber calling the thefts “outrageous” and pointing fingers at consumers. “All those people who think it’s a chic, trendy thing to own a pirated tape are accessories,” he said.

The Motion Picture Association of America, which monitors film piracy, offered a $500 reward for the missing prints. In England, where more reels had gone missing, Fox raised the incentive to $7000. There were no takers.

A few days after the theft in South Carolina, the film was discovered on a dirt road, the seals on the canisters unbroken: The thieves had apparently gotten cold feet about dubbing it. But in Overland Park, Riddick was committed. He kept the movie in his parents’ basement for several days before deciding to offer it to a local video store. The manager was noncommittal. When Riddick left to let him to think it over, the manager called the FBI.

Authorities set up a sting in Kansas City, where two agents posed as a married couple and invited Riddick to a hotel room to conduct a transaction. Riddick wanted $12,000 for Jedi but was willing to accept $10,000. After showing the agents one reel of the movie as proof, he was arrested. In December 1983, the 19-year-old got five years of probation and was ordered to perform 120 hours of community service.

When police asked why he did it, Riddick told them he was mad at his father.