Though he hadn’t yet stepped on to a professional playing field, Harold “Red” Grange, the nationally known star of the University of Illinois football program, had already gotten a crucial piece of advice from his agent, Charles “C.C.” Pyle: wear the raccoon coat.

Grange was making his first public appearance since announcing he would be dropping out of college to join the Chicago Bears and the National Football League. It was 1925, and team sports were still very much an organized form of athletic exploitation: owners received the lion’s share of the revenue and players had no aptitude for negotiation. Grange’s teammates on the Bears were making between $100 and $200 per game; his college’s faculty wondered why he’d give up his education for such little reward.

Grange, however, had no intention of playing for a pittance—Pyle had seen to it. A former movie theater manager who had met Grange during a film screening, Pyle was a born salesman who thought he could monetize Grange’s professional debut. With Grange already a fixture in newspapers around the country thanks to his collegiate performances, his league introduction would be a once-in-a-lifetime event.

Having Pyle negotiate his contract with the Bears netted Grange a staggering $100,000 his first season, thanks in large part to getting a percentage of ticket sales. Pyle also handled Grange’s personal investments, movie roles, and public appearances—right down to telling him how to stand out in the crowd at the Bears game with his peculiar choice of apparel.

Grange and Pyle couldn’t have known it at the time, but they were setting up a radical power shift in sports. The player’s representative, not the league, would be calling all the shots. And thus, the sports agent was born.

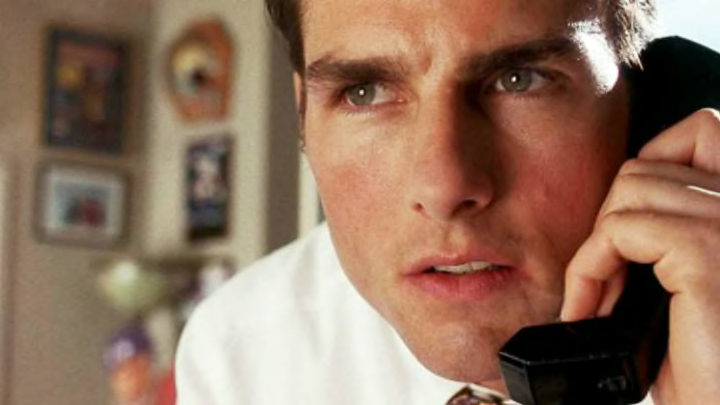

Grange signs a film contract; C.C. Pyle is on the far right. Wheaton

Frank Scott was no C.C. Pyle. He didn’t represent athletes during contractual negotiations and didn’t have a say in how they could obtain any additional financial reward while wearing a team uniform. But what Scott did was arguably just as influential: he taught players how to take advantage of their celebrity everywhere else.

In his role as a traveling secretary for the New York Yankees in the 1940s, Scott saw first-hand how players were being asked to make appearances or have their image reproduced for little compensation: Yogi Berra, he found, got a cheap watch every time he fulfilled an off-field obligation for the team. It rubbed Scott the wrong way. Soon, he was representing players like Berra, Joe DiMaggio, Mickey Mantle, and Willie Mays to secure commercial endorsements. In addition to a $30,000 salary for playing, Mantle found he could earn $70,000 for commercial spots. (Scott’s roster eventually grew to 91 players; he’d take 10 percent of their income.) While leagues still resisted negotiating with agents for salaries, athletes at least had new revenue opportunities.

The advent of television in the 1950s and 1960s brought with it additional endorsement offers, which called for a greater demand for business-savvy advisors. While Mark McCormack disliked the “agent” label, he’s widely regarded as magnifying Scott’s success a thousand times over. Armed with a law degree from Yale, McCormack signed golfer Arnold Palmer in 1960 and proceeded to market him across every conceivable platform, from engine oil to rental cars to speaking engagements. Palmer, who had been making $50,000 annually golfing, was reporting $500,000 in revenue within three years.

Seeing Palmer and McCormack’s partnership pay off, numerous agencies began springing up to help athletes handle endorsements. But their business savvy couldn't be directed at league negotiations. Team owners were under no obligation to deal with agents, and many simply hung up whenever they called. That would all change in 1975, when the take-it-or-leave-it ideal abused by the front offices would be brought down by a single player.

At the time Scott and McCormack were reaping rewards from ancillary income, agents didn’t have any real incentive to meddle in negotiations between talent and the clubhouse. Baseball in particular exerted a tyrannical hold on players, binding them to the first team they signed with for life unless they were traded. Without the opportunity to test the waters in the open market, they had no leverage when dealing with owners. Most evaluated deals themselves, or asked their fathers for advice.

Curt Flood was not a fan of the system. When the St. Louis Cardinals informed him he’d be traded to the Philadelphia Phillies in 1969, Flood responded with a word no major league office was used to hearing: no. He wasn’t going to go.

“I do not regard myself as a piece of property to be bought or sold,” Flood wrote to baseball’s commissioner, Bowie Kuhn, that year. Whether Flood—a black player who had seen his share of prejudice—intended the statement to be metaphorical or not, the intent was clear. He was tired of not having a voice.

Flood sued Major League Baseball for violating antitrust laws. “The team that makes me the best offer” is the one he wanted to play for, he said.

The controversy cost Flood his passion for the game: He quit in 1972, the same year the Supreme Court ruled against him. But their decision indicated that collective bargaining could put an end to the monopoly; public opinion began to turn against corporate monopolies. After two players started games without contracts in 1976 and were ruled free agents, the dam burst open. Agents could now shop players, playing sides against one another.

Change was already taking place in other sports, as well. In the NFL, quarterbacks were receiving unprecedented attention. When draft pick Steve Bartkowski was at a contract impasse with the Atlanta Falcons in 1975, he reached out to a college friend named Leigh Steinberg. Steinberg got the now-defunct World Football League to bid on his services, forcing the Falcons to cough up a record $625,000 for a rookie signing. Steinberg went on to become one of the most successful agents in the business, increasing awareness of the potential for lucrative deals. Sports leagues were beginning to profit handsomely from broadcast rights to games—beginning with Monday Night Football on ABC—and players were looking for their share.

With richer revenues from television, team owners were going to have to embrace the idea of profit-sharing if they expected to bolster their line-ups with talent. In 1979, Nolan Ryan signed baseball’s first contract worth a million dollars a year.

That would turn out to be a bargain. In the coming decades, salaries would swell, culminating in agent Scott Boras scoring two of the richest deals in baseball in 2001 and 2008 for client Alex Rodriguez: the contracts were in excess of $250 million each. In 2014, Excel, a management company out of Tampa, accrued $700 million in off-season contracts.

Not all agents have acted as cash dispensers. When NFL prospect Ricky Williams entered the league in 1999, he had rap artist Master P’s agency come to the table on his behalf. Williams walked away with a one-sided deal that left him to chase money based on performance incentives.

Today’s agencies are often huge conglomerates that deal with everything from sneaker branding to advising athletes on investments. In the 1980s, the ProServ agency helped turn Michael Jordan into a household name, multiplying his league salary several times over in endorsements and turning athlete management into an art. By the time they secured a Nike deal for Jordan in 1984, the sports agent had become a fully integrated part of an athlete's career.

Many agents engage players on a personal level, telling them exactly how many times they need to bench 225 pounds in order to impress at the NFL’s Scouting Combine; Jordan's agency cashed his checks and gave him an allowance. Thanks to pioneers like Pyle, McCormack, and the rest, players today can enjoy a level playing field, focusing on performance while letting someone else clash heads with management.

And while ruthlessness in an agent isn’t a prerequisite, it doesn’t hurt. C.C. Pyle’s initials, after all, stood for “Cash and Carry.”