The first thing the assembled media noticed about Albert Einstein was not his energetic tuft of hair, which was covered by a felt hat. Nor was it his formidable intellect, responsible for a groundbreaking theory of relativity that had captivated the world—at the time, Einstein spoke no English.

It was the violin he had brought with him from Holland, a violin that had occupied his time during a week-long voyage on the steamship Rotterdam. Einstein often played music to slow his frenetic brain processes and help him relax. As photographers snapped picture after picture, capturing the arrival of one of the world's greatest minds on U.S. soil, the scientist clutched his instrument like a life preserver. If he couldn’t play it, maybe he’d at least be calmed by how it felt in his hand.

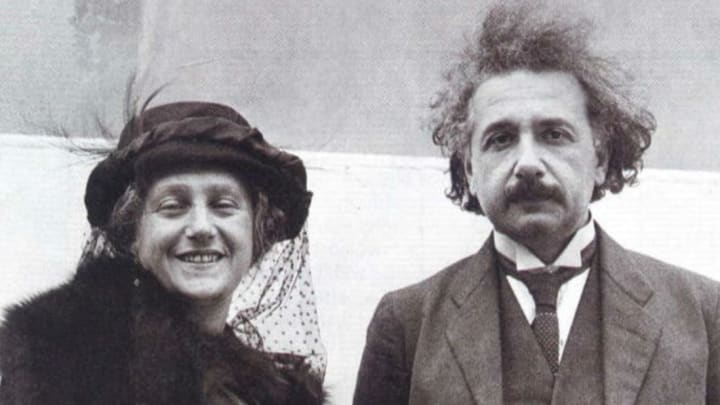

After a half-hour, an annoyed Einstein had had enough. He waved off the press, leaving his English-speaking wife, Elsa, to receive their questions. He had only been in the States for a short time, but for a man who was uncomfortable with attention, crowds, and the persistence of the media, the next two months would bring him to a point of near exhaustion. If it had been up to him, he may never have come at all—but there were other, far more important reasons for visiting.

Einstein arrived in New York City on April 3, 1921, the same year he won the Nobel Prize in Physics. At 42, he was an unlikely celebrity, a man with a compact presence who had spent 15 years on a theory that no layperson understood; they just knew it was important.

The media members who sat with him—some German-speaking, others relying on interpreters—tried to force some kind of digestible explanation out of him. What, exactly, is the theory of relativity?

“Falling bodies are subjects independent of clauses,” he told a wire service reporter, “and light in diffusion is bent.” Then he reclined back, unwilling to waste any energy trying to explain further. Einstein was fond of saying only 12 scientists in the world understood it, and those 12 were enough to spread the gospel in the scientific community.

Elsa was of little help. “In its details it is too much for a woman to grasp,” she said.

It was, in effect, a dual language barrier, and reporters would very quickly move to Einstein’s thoughts on American culture. He marveled that women here dressed “like countesses,” even though they might be coat check girls. He condemned Prohibition and appeared thunderstruck at the notion of banning tobacco. He liked movies, but felt they were not yet artistically developed. He thought our bathrooms were marvelous. The narrative—the great genius bewildered by this industrial nation—came to dominate media coverage of Einstein’s visit.

Though it was said Einstein was more famous than Babe Ruth at the time, not everyone was willing to join the thousands that lined the streets as police escorted him to his room at the Commodore Hotel. One woman dismissed talk of the scientist’s achievements as “highbrow bunk.” Bruce Falconer, a city official, delayed Einstein being handed the key to the city because he was unfamiliar with his work and argued no one could prove his claims.

As Einstein traveled to appear at universities in Boston and Chicago, his impatience grew along with his notoriety. Reporters said trying to speak with him was like “trying to obtain the confidence of a bashful child.”

The reason Einstein was willing to be put on public display had very little to do with his actual work and more to do with the celebrity that had come out of it. He did receive some compensation from universities like Princeton, but his actual ambition was to champion the cause of his travel companion: Chaim Weizmann.

Weizmann was chairman of the World Zionist Organization. Earlier in 1921, he had contacted Einstein and extended an invitation to travel to America. Weizmann sought to use Einstein’s fame to drum up both publicity and funds for a center of learning he wanted to build in Jerusalem.

Einstein felt an obligation to help. His own Germany was becoming hostile to the Jewish faith, and the men believed a university would help cement the history and heritage of the Jewish population. (Already, the scientist felt criticisms of his work were the product of anti-Semitism.) Weizmann extended invitations to as many prominent, wealthy potential investors as he could find, and Einstein was his passport to New York's upper echelon. Physicist Michael Pupin later wrote in a letter to Einstein, “your involvement in the social and political advancement of your ingenious and long-suffering people will serve as a model example for other men of science.”

But not everyone felt Weizmann and Einstein's passion, and some declined the offer even to meet. The men were also faced with the resistance of Felix Frankfurter, a Harvard professor who worried that Einstein's requests of upwards of $15,000 for university lectures would be perceived as crass and hurt the Jewish cause as a whole. Einstein defended himself by writing that friends in Holland had “very strongly advised me to set such high demands.” (He did not receive his asking price.)

The center, Hebrew University, would eventually be built four years later in Jerusalem, due in part to a number of Jewish physicians—Einstein numbered them at 6,000—who contributed to their cause. The scientist later wound up donating his pages of notes that comprised the theory of relativity to the school.

At the end of May, Einstein set sail for a stay in England. Departing close to Memorial Day, his exit wasn’t greeted with the same exhaustive coverage as his arrival. Days before his trip, he wrote to a friend that the two months spent in America were “horrendously strenuous” and that he was looking forward to settling in back home.

The Washington Herald was among the last of the papers to grab a sound bite. Before the reporter could begin, a fatigued Einstein made a request.

“I prefer to talk about the weather—the—well, anything but relativity.”

Additional Sources:

“Einstein, Theory Founder, Bewildered by New York,” Oakland Tribune, April 4, 1921; “Einstein Here to Mystify U.S. With Relativity Theory,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 3, 1921; “Einstein on Irrelevancies,” The New York Times, May 1, 1921.