In a memo dated November 30, 1957, an agent with the Federal Bureau of Investigation identified as “A. Jones” raised an issue of critical importance: "Several complaints to the Bureau have been made concerning the 'Mad' comic book [sic], which at one time presented the horror of war to readers."

Attached to the document were pages taken from a recent issue of Mad that featured a tongue-in-cheek game about draft dodging. Players who earned such status were advised to write to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and request a membership card certifying themselves as a “full-fledged draft dodger.” At least three readers, the agent reported, did exactly that.

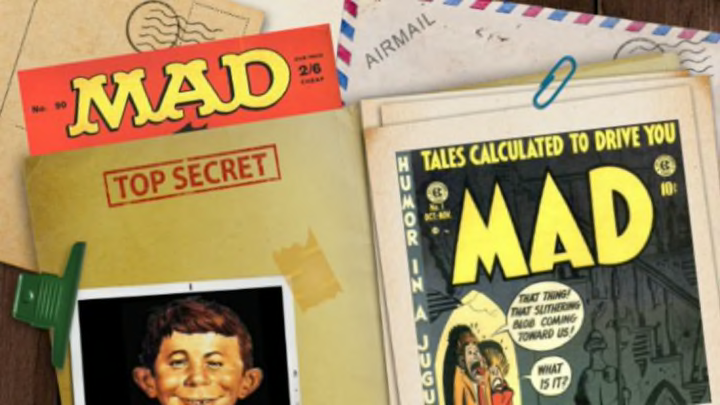

Mad, of course, was the wildly popular satirical magazine that was reaching upwards of a million readers every other month. Published by William Gaines, who had already gotten into some trouble with Congress when he was called to testify about his gruesome horror comics in 1954, Mad lampooned everyone and everything. But in name-checking the notoriously humorless Hoover, Gaines had invited the wrong kind of attention.

The memo got several facts incorrect: Mad had switched from a comic book to a magazine format in 1955, and it was Gaines’ E.C. Comics that had “presented the horror of war” in other titles. Despite getting these crucial pieces of information wrong, Jones didn’t hesitate to editorialize: "It is also of interest to note that…it is rather unfunny.”

The agent recommended the Bureau’s New York offices “make contact” with Mad’s headquarters to “advise them of our displeasure” and to make sure “that there be no repetition of such misuse of the Director’s name.”

Less than a week later, the Feds entered the hallowed hallways patrolled by Alfred E. Neuman. Their New York office would later report to Hoover directly that they had met with John Putnam, the magazine’s art director. (Conveniently, Gaines was not in that day.) Putnam told the agents he regretted the magazine using Hoover’s name and that nothing malicious was intended:

Putnam said that the use of the membership card and the name and address of the Director at the end of the game was referred to in their business as a 'gag' or 'kicker' in the same way that a comedian like Bob Hope or Milton Berle might use it.

Putnam swore that Mad would never again take Hoover’s name in vain; Gaines sent off a letter of sincere apology to the Director.

The Smoking Gun

Just two years later, in January 1960, Agent A. Jones was forced to file a second notice about the shenanigans at Mad. A recent issue had made not one, but two derogatory mentions of Hoover, including one in which he is blatantly and disrespectfully portrayed as being associated with a vacuum cleaner, “The Honorable J. Edgar Electrolux”:

Obviously, Gaines was insincere in this promise…and has again placed the Director in a position of ridicule…it is felt we should contact Gaines…and firmly and severely admonish them concerning our displeasure…

It was by now clear Mad was not only polluting young minds, but that Gaines had absolutely no regard for the honorable Hoover’s position.

In June 1961, the FBI’s worst fears had been realized. Detailing an investigation into a Seattle-area extortion attempt led to the following:

Investigation … resulted in gaining admissions from the victim’s 12-year-old son and an 11-year-old companion that they had gotten the idea of preparing an extortion letter after reading the June issue of 'Mad' magazine.

Working in concert with the Buffalo field office, the FBI determined another letter had been sent by a young boy demanding money in the style of a recent issue’s extortion advice. And there was a third under review that was sent to the agent of some professional wrestlers.

Mad was quickly becoming the scourge of the federal government. The FBI suggested the magazine be brought to the attention of the Attorney General for “instructing [readers] to deliberately violate the Federal Law.” They tried reaching out to Gaines, who was on vacation. (Time and again, Gaines simply not being in the office when called upon seemed to confound the FBI.)

Agent A. Jones, having exhausted all attempts to reason with these irresponsible anarchists, filed one last memo:

Despite assurances, they have continued to publish slurring remarks about the Bureau. In view of this situation, it was deemed useless to protest all such irresponsible remarks to a magazine of this poor judgment and capriciousness … we will have to wait and see if our action will result in increased discretion by this publication.

Poor A. Jones was unable to put an end to Mad’s reign of terror. But the magazine redeemed itself somewhat. In the 1970s, when the Bureau was trying to suppress the influence of the Ku Klux Klan, an agent suggested they copy and distribute a sticker from the magazine that read, “Support Mental Illness—Join the Klan!”

Hoover said no.

Additional Sources:

The Smoking Gun.