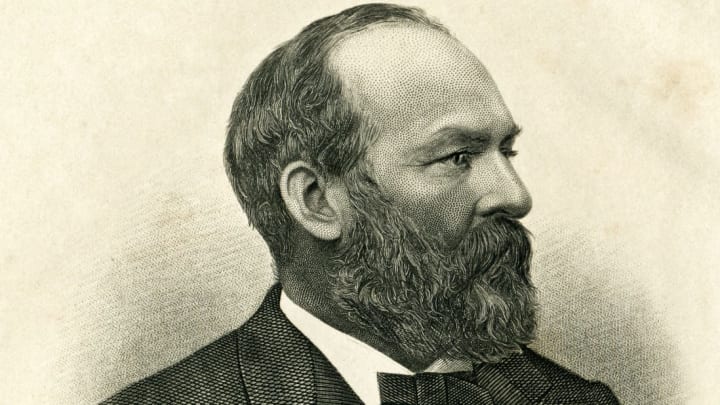

Owing to his untimely demise at the hands of assassin Charles Guiteau in 1881, 20th U.S. president James Garfield served only seven months in office, the second-shortest tenure after William Henry Harrison. (The equally unfortunate Harrison famously succumbed to pneumonia—though it might have been typhoid—one month into his term.) Not quite 50 at the time of his passing, Garfield nonetheless managed to pack a lot of experience into his short but eventful life. Read on for some facts about his childhood, his election non-campaign, and why Alexander Graham Bell thought he could help save Garfield's life. (Spoiler: He couldn't.)

1. He originally wanted to sail the open seas.

Garfield was born in Orange, Ohio on November 19, 1831. He never had a chance to know his father, Abram, who died before James turned 2 years old. As a child, Garfield was enamored with adventure novels and imagined a career as a sailor. "Nautical novels did it," he once said. "My mother tried to turn my attention in other directions, but the books were considered bad and from that very fact were fascinating." As a teenager, he got a job towing barges, but that was about as far as his seafaring would get. He attended the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (now called Hiram College) in Hiram, Ohio and Williams College in Massachusetts before settling in as a Greek and Latin teacher at Hiram, where he would later become president.

2. He was a Civil War veteran.

If Garfield longed for adventure, he eventually found it, though perhaps not quite in the way he anticipated as a child. After being elected to the Ohio senate in 1859, Garfield joined the Union army at age 29 during the outbreak of war against the Confederates in 1861. Garfield saw combat in several skirmishes, including the Battle of Shiloh and the Battle of Chickamauga, before then-president Abraham Lincoln convinced him to resign his military post so he could devote his time to advocating for Ohio in the House of Representatives in 1863. He became the leading Republican in the House before being elected to the Senate for the 1881 term.

3. He never pursued presidential office.

Garfield thought he was attending the 1880 Republican National Convention to stump for Treasury Secretary John Sherman as the party's presidential candidate. Instead, the convention came to an impasse over Sherman, James Blaine, and Ulysses S. Grant. To help unclog the stalemate, Wisconsin's delegation threw Garfield's name into the hat as a compromise candidate. Not only did he win the election (opposing Democrat Winfield Scott Hancock), but he became the only sitting House member elected president. The whole process took Garfield by surprise, as he once told friends that "this honor comes to me unsought. I have never had the presidential fever, not even for a day."

4. He got caught up in an immigration scandal.

Just weeks before the general presidential election in November 1880, Garfield's political opponents tried to deal a fatal blow to his campaign by circulating a letter Garfield had written to an associate named H.L. Morey addressing the matter of foreign workers. In it, Garfield supported the idea of Chinese laborers, a controversial point of view at a time the country was nervous about immigration affecting employment. Democrats handed out hundreds of thousands of copies of the letter in an effort to sour voters on his candidacy. In Denver, the prospect of foreign workers prompted a riot. At first, Garfield remained silent, but not because he was ashamed of the letter. He simply couldn't recall writing or signing it—it was dated just after he was elected to the Senate, and he had signed lots of letters that he and his friends wrote in reply to the congratulatory messages he had received. But after consulting with his friends he issued a denial, and after seeing a reproduction in a newspaper, Garfield announced it was a phony. Furthermore, "H.L. Morey" didn't seem to exist. Turns out, the letter was planted by the opposition to discredit Garfield's name. Journalist Kenward Philp, who published the letter, was put on trial for libel and forgery but acquitted. One witness who claimed they met Morey was jailed for eight years for perjury.

5. He defended civil rights.

Several presidents in or near Garfield's era—Andrew Johnson, Woodrow Wilson—had less than flattering views on Reconstruction and civil rights. But Garfield made his opinion abundantly clear. Speaking during his inauguration, Garfield celebrated the dissolution of slavery and called it "the most important political change" since the Constitution. Garfield also appointed four black men to his administration, including activist Frederick Douglass as recorder of deeds for the District of Columbia.

6. He didn't get particularly great medical care after being shot.

A former Garfield supporter, Charles Guiteau, was erroneously convinced that Garfield owed him a European ambassadorship. After his letters and drop-ins were ignored by the administration for months, he shot Garfield twice at a train station in Washington, D.C. The president was quickly tended to by a number of physicians in the hopes he could survive the bullet stuck in his abdomen, but the doctors didn't bother washing their hands before sticking their fingers in his wound. (At the time, the idea of an antiseptic medical environment was being promoted but not widely used.) For two weeks, Garfield languished in bed as his caregivers attempted to remove the projectile but succeeded only in worsening both the incision in his stomach and the accompanying infection. A heart attack, blood infection, and splenic artery rupture followed. He hung on for roughly 80 days before dying on September 19, 1881. Guiteau was hanged for the crime in 1882.

7. Alexander Graham Bell tried to save his life.

During Garfield's bedridden final days, the public at large tried their best to lend sympathies and possible solutions. One letter writer suggested that doctors simply turn him upside-down so the bullet would fall out. A slightly more reasonable—but no more effective—tactic was offered by Alexander Graham Bell. Inviting a large measure of respect for his invention of the telephone, Bell was allowed to use a makeshift metal detector over Garfield's body to see if the electromagnetic fields would be disrupted by the presence of the bullet, revealing its location in Garfield's abdomen. Bell was unsuccessful, though he reportedly did manage to detect the metal in the president's mattress.

8. A classical statue was erected in his honor soon after his death.

Despite his short and somewhat uneventful tenure, Garfield quickly (as in, within six years) received an honor equal to more renowned American presidents. Sculptor John Quincy Adams Ward, who is probably best known for his oversized bronze of George Washington that stands on the grounds of his inauguration at Federal Hall in New York, unveiled his Garfield monument in 1887 at the foot of the Capitol building. The statue, which depicts Garfield giving a speech, also sports three figures along its granite pedestal base: a student (representing Garfield's stint as a teacher), a warrior (for his military service), and a toga-sporting elder statesman (to signify his political career).