The last time anyone could say with certainty that they saw the real Bobby Dunbar was August 23, 1912. Later described in newspapers as stout “but not fat,” rosy-cheeked, and sporting a straw hat, the 4-year-old son of Percy and Lessie Dunbar had accompanied his parents and their friends to a weekend camping retreat at Swayze Lake near Opelousas, Louisiana. Percy, who ran a successful real estate and insurance company, quickly left to attend to business; Lessie stayed behind to care for Bobby and his 2-year-old brother, Alonzo.

The morning they arrived, Bobby left his mother to go watch his father’s friend, Paul Mizzi, shoot fish in the murky water, a muddy splash of swamp surrounded by trees. As lunchtime neared, Lessie began calling everyone to help set up for the meal. According to a contemporary newspaper report, as Mizzi and Bobby walked to the dining area, the young man told the little boy to get out of the way; Bobby laughed and said something sassy, then "disappeared like magic."

When Bobby failed to reappear, his mother grew frantic. It's easy to imagine her worst fears about the alligator-infested waters nearby. By the time Percy returned to the lake around noon, he found friends searching for his son, and more than 100 locals quickly joined the search party.

For over a week, they combed the swamp and surrounding area, looking for bones, a body, or Bobby’s straw hat. Gators dragged from the water had their bellies sliced open to check for body parts. Some of the men set off dynamite in the water to see if his corpse would rise to the surface.

The good news was that nothing was found. The terrible news was that nothing was found. For eight excruciating months, Percy and Lessie were in a state of shock, unsure whether to grieve for Bobby or hold on to a thread of hope.

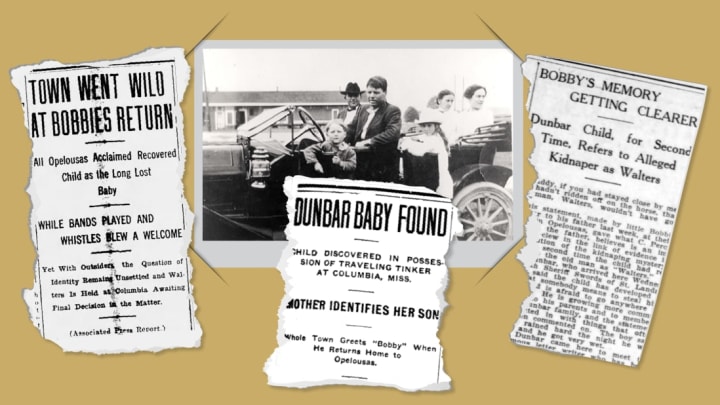

Then, in April 1913, Percy got a telegram from Columbia, Mississippi. The telegram said that a transient had been spotted with a boy matching Bobby’s description. Within days, Percy and Lessie were convinced it was their Bobby. They would take him in, raise him, and love him, even as the man accused of kidnapping Bobby protested his innocence—even as he insisted the boy’s real name wasn't Bobby Dunbar, but Bruce Anderson, his traveling companion.

The Dunbars hadn't found their child, he said. They had kidnapped someone else's.

BOBBY LOST AND FOUND

The confusion surrounding the Dunbar mystery seems hard to understand today. With DNA testing, questions over Bobby's identity could now be resolved in a laboratory. But in the Louisiana of 1912, a lack of forensic science, among other issues, helped perpetuate a tragedy that wound up affecting multiple generations of families.

Owing to the wealth and influence of the Dunbars, Bobby’s disappearance earned plenty of attention. At first, Percy sent hundreds of postcards with Bobby’s photo and description to town officials in Florida, Texas, and other states. He offered a $5000 reward for information leading to Bobby’s recovery, with the local citizens and the Planters National Bank of Opelousas joining together to offer another $1000. Newspapers around the country made it a national headline. Percy traveled to orphanages around the state, hoping to see that his fair-haired, blue-eyed boy had been safe and sheltered the entire time.

As is often the case with missing parties, the search turned up several leads without merit. But according to the book A Case for Solomon, co-written by Bobby’s granddaughter Margaret Dunbar Cutright, a few weeks after Bobby's disappearance the family received a letter from Poplarville, Mississippi, saying that a boy looking remarkably like their own had been seen in the company of an itinerant worker. Fatigued by false hope, Percy asked his brother, Archie, to go to Poplarville on his behalf. But Archie reported that the boy was not Bobby.

In April 1913, eight months after Bobby had last been seen, a telegram came from Columbia, Mississippi, saying that a boy looking very much like Bobby had been seen in the company of an itinerant worker named William Cantwell Walters—likely the same itinerant worker seen in Poplarville. After asking a favor from a sheriff friend, Percy was able to have authorities in Columbia detain Walters and the child until the Dunbars could judge for themselves.

The Dunbars arrived by train and were greeted by a cluster of locals who wondered if the mystery of the missing Dunbar boy was about to unravel in their hometown. But accounts vary about precisely what happened next. In one version of the story, Percy was alleged to have cautioned his wife not to see Bobby right away, since the townsfolk seemed ill-at-ease and may have had intentions to beat, or even lynch, Walters, a suspected kidnapper, if he was proven to be at fault. Another description has Lessie racing to meet Bobby for the first time and being uncertain if it was her son; she felt his eyes were too small. For his part, Bobby shrunk away, insisting his name was Bruce.

The next day, Lessie was permitted to give the boy a bath. After examining his moles and other distinguishing features, she pronounced him to be her Bobby without a doubt. The child seemed to have had a change of heart, too, embracing her and calling her “mama.”

It was a fairy tale ending. The Dunbars quickly returned home to Opelousas, where a veritable parade was awaiting them. Their son was invited to ride a fire truck and celebrated at every turn; he soaked up the adulation.

Newspapers eager to promote a feel-good story largely backed the Dunbars’ assertion, though some of the copy seemed to hint at the same doubt Lessie had initially experienced. “The Dunbars say they have identified the child by marks on his body,” The Los Angeles Times reported, “and they hope that the environment of their home will reawaken some memories in his mind by which they will be more certain.”

A CRIME WITH NO MOTIVE

Back in Mississippi, Walters was dumbfounded. Awaiting extradition to Louisiana on a capital charge of kidnapping that could see him executed or sent to prison for life, he told anyone who would listen that it was the Dunbars who were the kidnappers. The boy was Bruce Anderson, the son of Julia Anderson, he said, a woman from back home in North Carolina who had been involved with Walters’s brother for a time. Although the stories would differ, Walters maintained that a little over a year prior he had agreed to look after Bruce because he felt Julia didn’t have the means to provide for him. As a traveling worker, or “tinker,” Walters found that having Bruce around made strangers more likely to take him in for food and lodging.

It seemed easy enough to clear the matter by inviting Julia, ostensibly the boy’s actual mother, to support his story. Eager to have a possible exclusive, a New Orleans newspaper paid for Julia to travel from her home in North Carolina in May 1913 to meet Bobby. She was asked to identify her son among a group of several boys.

Just as Lessie had hesitated, Julia also didn’t seem sure she was meeting her son. Maybe it was Bruce, but perhaps it was not. The media latched on to her hesitation—surely a mother could identify her own child—and used it to bolster the case against Walters, who was finally extradited to Louisiana in 1914 to stand trial for the kidnapping of the Dunbar boy.

It took two weeks for an Opelousas court to try and convict Walters, who continued to protest his innocence. Julia was also scheduled to testify on his behalf, but fell ill and instead gave a statement from her bed. Wanly, she insisted "Bobby" was Bruce and that Walters should not be condemned for any crime. The jury was not swayed, and sentenced Walters to life imprisonment.

As bleak as things were for the Anderson side of the controversy, Walters did get one break. His lawyer was successfully able to argue that Louisiana law regarding kidnapping was unconstitutional by focusing on a legal technicality based on an omission in the text. That appeared to sway the court into having the case thrown out. Mindful of how expensive it was to try him the first time, the district attorney declined to attempt a second conviction. Walters was free to go. Meanwhile, Julia Anderson was married and starting another family.

DISCOVERING THE TRUTH

Bobby continued life as a Dunbar, remaining in Louisiana and becoming a salesman for Briggs Electrical Supply. He had four children of his own, before succumbing to a heart attack at the age of 58 in 1966. He never seemed to express any curiosity about his national fame, or the strange circumstances surrounding his alleged disappearance.

Questions over Bobby’s lineage would have likely ended with the court case had it not been for the work of Cutright, who became interested in her grandfather’s case in 1999. Her father, Bobby Dunbar Junior, gave her a massive scrapbook of newspaper clippings, much of it revealing the contradictory stories of how unsure Lessie had been about her son’s reappearance. She also dug up the case file kept by Walters’s attorney, reading testimony from several people who had placed Walters and Bruce together.

In 2004, she was able to convince her father to take a DNA swab and see if it matched with a sample taken from the son of Bobby’s brother, Alonzo. The results proved they were no relation: Bobby Dunbar was almost certainly Bruce Anderson. The real Bobby Dunbar likely met a swift and unfortunate fate at Swayze Lake, perhaps left alone just long enough to disappear into the water.

The DNA solution provided an answer, but it could never provide context. Why, Cutright wondered, did Percy and Lessie so readily accept a child that was not their own? And why did Julia Anderson waver when presented with the opportunity to conclusively identify Bruce?

The answer may lie in the wealth that the Dunbars enjoyed—not as a means of influence, but as a promise for a better life. Julia had, after all, already allowed Walters to care for Bruce. Now he’d be in a steady home and a supportive family.

Percy and Lessie’s motives are more difficult to understand. It’s possible the weight of their grief caused them to latch on to the fantasy of their child being returned to them. Maybe Lessie, who had grown frail during the search, embraced the lie to the extent that Percy felt the need to go along with it. Perhaps Bruce, only around 5 years old, was able to comprehend that his new life of riding fire trucks and being the toast of the town was better than trailing Walters as he performed odd jobs in odd towns.

The Dunbars separated in 1920 and divorced soon after. Some time later, Lessie wrote a letter to her granddaughter that made reference to her “shell of grief.” It’s hard to know whether she was referring to the pain of losing a child, the regret of taking one—or both.