The editors at Super Teen had some ironclad rules about the profiles of teen idols featured in their pages each month. An actor or musician’s bad behavior was never discussed; long-term relationships were barely mentioned. Most importantly, there was a permanent ban on chest hair.

"If they have hairy chests, you’ll see them with their shirts buttoned up," Bob Schartoff, the magazine’s creative director, told the New York Daily News in 1982. Facial hair was also verboten. When a reporter offered a hypothetical—say Scott Baio grew a beard—Schartoff said the Joanie Loves Chachi star would effectively be excommunicated from his pages.

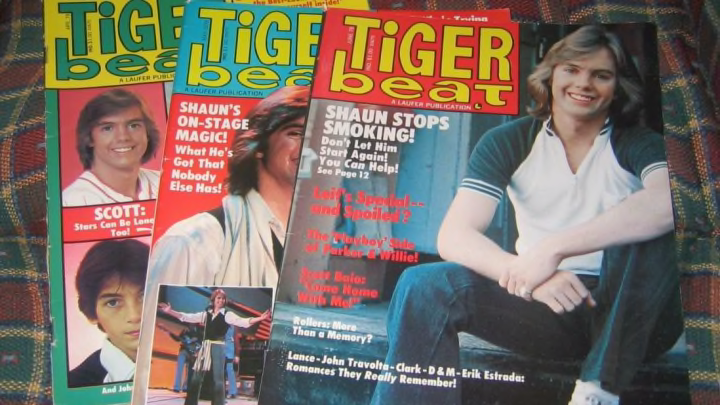

Super Teen, Tiger Beat, Bop, 16. From the 1960s to the 1990s, these glossy, primary-colored magazines that looked like the inside of a 13-year-old girl’s locker door sold hundreds of thousands of copies each month and provided gleefully superficial insight into the non-threatening sex symbols of their respective eras. Jason Bateman was photographed cradling a Teddy Ruxpin; Matt Dillon could be seen eating pizza like any normal person. Readers were often referred to in the second-person to better help them visualize an innocent evening with their celebrity crush. ("Are YOU the Kind of Girl Adorable Tim Hutton is Looking For?")

At times, the magazines anticipated the evolution of dimpled pin-ups into actual marquee stars (Tom Cruise, Michael J. Fox). Other times, there was a lot of ink spilled over the internal workings of Menudo. All of it was meant to entice their demographic of 11- to 14-year-old girls, which some editors were rather blunt about diagnosing.

"The typical reader … is shy, self-conscious, quiet, afraid of boys, and not into dating," Schartoff said. "They’re 'B' students and not the prettiest one in class."

The idea of pandering to fans of clean-cut performers with breathless magazine prose can be traced back to Elvis Presley. In the late 1950s, magazines like 16 went from printing song lyrics to relaying details of what it might be like to date the King, crooner Pat Boone, or actor Tab Hunter. When the Beatles arrived stateside in 1964, the ensuing pandemonium flowed into what was quickly becoming a subgenre of publishing—teen idol worship.

Charles Laufer took notice. A journalism and English teacher at Beverly Hills High School, Laufer thought a magazine devoted to teen interests would be a success. He launched Coaster, a regional publication for Long Beach locals, in the 1950s. It didn’t succeed until he realized his mistake: Boys didn’t want to sit down and read about celebrity lifestyles. Girls did.

Laufer renamed the magazine Teen and watched it grow into a hit before leaving to start Tiger Beat in 1965. His timing was fortuitous: The Monkees were just beginning to explode in popularity, and Tiger Beat saw its circulation rise when it profiled the fun-loving group. Laufer sold Monkees fan club memberships, posters, and books before he sold Tiger Beat itself to the Harlequin romance house in 1978 for $12 million.

The magazines—which began to number in the dozens and eventually in the hundreds—were usually cyclical in nature, their sales rising and falling depending on who happened to be in favor with teen girls at any given time. In the '70s, John Travolta and Erik Estrada moved copies. In the '80s, it was soap star Jack Wagner, Scott Baio, Rick Springfield, and Growing Pains actor Kirk Cameron, who was such an ideal of non-threatening sexuality that he became a cover fixture.

Typically, editors would get stacks of photos from publicity departments—like Don Johnson standing next to an inflatable alligator—and hope that a competing magazine wouldn’t be running the same shot that month. Interviews were dependent on a star’s level of fame. Some, like Eight is Enough heartthrob Adam Rich, sat for interrogations with editors; others, like Tom Cruise, largely shunned any personal involvement, fearing they’d be typecast in juvenile roles. If a star did consent to an interview, their conversation would likely be parsed over several months to make it last.

Negativity was a killer. When Karate Kid star Ralph Macchio got married in 1987, editors told fans he "needs your support," rather than, say, trying to take down the woman who dared to take Macchio off the market. When a celebrity made a less-than-flattering impression—like the time the 13-year-old Rich told his publicist to "shut up" during one Super Teen sit-down—it was never disclosed. When John Schneider walked off the set of The Dukes of Hazzard over a pay dispute, fans wrote in to express their disappointment. Financial strikes broke the fantasy, and Schneider-related pin-up sales slumped.

The adulation could be mortifying for actors trying to take their careers seriously, particularly when they were surrounded by the kind of Trapper Keeper collage and single-syllable vernacular favored by the publications. (Pictures were "pix," facts were "fax.") Others—or their publicists—saw the teen mags as a vehicle to promote themselves. Rick Springfield was said to have hung around 16’s New York offices looking for a mention before his big break. In 1979, Kevin Spacey showed up for a cattle call to find a new “teen idol” for Tiger Beat. (He never joined the ranks of Cameron and the rest.)

At its peak in the 1970s, Tiger Beat and its sister publications reached roughly 2 million readers a month. Others got by on as little as 135,000 paid copies sold. The 1990s diversified with titles like Teen People and Sassy, publications that brought a stronger editorial voice to readers and eased up on the kind of copy that didn’t exactly enable feminism. ("Sail Away with RALPH MACCHIO!")

In the 1990s, the popularity of the Backstreet Boys and *NSYNC helped keep Tiger Beat and the others afloat, but not for long. The internet and social media excised the middleman, allowing stars to control their exposure and deliver calculated glimpses into their lives without Teen Beat interfering. Many enduring titles folded. Tiger Beat sold to a group of investors—which included Nick Cannon—for $4 million in 2016, with plans to modify the brand for a digital era.

The tens of thousands of magazines once revered like pop culture gospel are now relegated to recycling bins, basements, or eBay, with one cover or interview largely indistinguishable from another. All readers wanted was some gossip, some advice, and to find out whether or not Corey Haim liked pepperoni on his pizza.

"Actually," Teen Star Photo Album editor Lori Bernstein told the Palm Beach Post in 1988, "they all kind of say the same things."