When actress Suzanne Cryer appeared in the Neil Simon-penned play Proposals in New York City in 1997, she could hear the audience whispering. It shortly dawned on her what the murmuring was about. People were saying “yada, yada, yada.”

Cryer had just appeared in an episode of Seinfeld titled “The Yada Yada,” in which her character Marcy uses the phrase as a kind of exposition filler in conversation—one that George Costanza (Jason Alexander) increasingly finds suspicious.

There’s no doubt most people in attendance for Proposals, as well as everywhere else, are familiar with the idiom thanks to that episode. But yada yada yada as a piece of American slang can be traced much further back than George’s relationship troubles.

Yada, Yatter, and Yaddega

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, yada yada yada is likely a linguistic descendant of yatter, a Scottish word dating to 1827 that means “idle talk” or “incessant chatter or gossip.” Yatter was malleable and may have influenced similar expressions in Yiddish, like yatata or yaddega-yaddega, in the early to mid-20th century, to denote a blithe response to conversation or content. It often meant, “Then other things happened, but it’s not relevant or interesting.”

The phrase appeared in gossip columns and comic strips of the 1940s, as well as a Judy Garland and Bing Crosby duet, “Yah Ta Ta.” (“When I’ve got my arm around you and we’re going for a walk, must you ya-ta-ta, ya-ta-ta, talk talk talk?”) Most notably, Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein composed a different song, “Ya-ta-ta,” for the musical Allegro in 1947, which was intended to satirize the sort of insubstantial small talk found at gatherings. Instead of dialogue, cast members at a cocktail party just repeatedly murmured, “yatata yatata.”

The yada yada yada version may have been coined by controversial stand-up comedian Lenny Bruce, who once wrote “yaddeyahdah” in his 1967 book, The Essential Lenny Bruce. Bruce may have been influenced by Jewish comedians he watched growing up in the 1940s—comics who may, in turn, have adopted the phrase from vaudeville performers.

It’s hard to know whether Bruce or simply cultural traditions kept the phrase afloat. But either way, the phrase was an uncommon sight in print until the 1970s. In a 1975 profile of actress Elizabeth Ashley, her use of yada yada yada is noted, which author Sally Quinn defined as “a nonsense line denoting unnecessary explanation.”

Later, in 1988, Miami Herald book reviewer Debbie Sontag began a review of Jay McInerney’s Story of My Life with: “Yada, yada, yada. That’s how celebrity writer Jay McInerney’s 20-year-old narrator, the brash-tongued, screwed-up Alison Poole, describes the way her friends drone on, repeating themselves but saying very little. Well, yada, yada, yada is the story of Story of My Life. It dribbles on and on, readable but not compelling, a yada-yada novel about yada-yada people.” (Sontag did not like the book.)

“The Yada Yada”

Yada yada yada is similar to other hand-wave expressions like etc., or blah, blah, blah. Yet yada yada yada didn’t seem to enjoy the same popularity as those conversation fillers until it became part of the Seinfeld lexicon and its laundry list of idioms (“the double dip,” “spongeworthy,” and so on).

Credit for its currency in modern language goes to Peter Mehlman, a Seinfeld writer who told Cracked in 2023 that he once encountered an editor who used the phrase yada yada. It occurred to Mehlman that, for his script, yada yada could be symbolic of details that the speaker didn’t want the listener to be privy to.

Mehlman co-wrote the script with Jillian Franklyn, who kept in her notes a reminder to play with the phrase blah blah blah. A similar one, yada yada yada, won out, however.

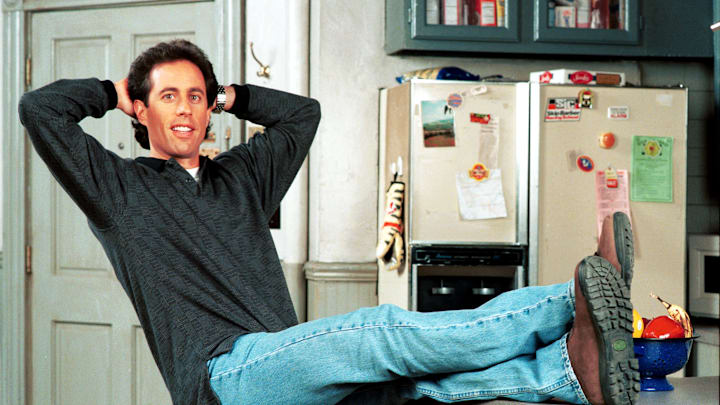

In the episode, which aired in 1997 during the show’s eighth season, George is seeing Marcy (Suzanne Cryer) , who tends to say “yada yada yada” over seemingly pertinent details.

“I notice she’s big on the phrase ‘yada yada,’” Jerry observes. “That’s good. She’s very succinct.” (Jerry is more concerned that his dentist, Tim Whatley, has abruptly converted to Judaism and now appears too comfortable making Jewish jokes.)

George is initially impressed by Marcy’s brevity. (“So, I’m on 3rd Avenue, minding my own business, when yada yada yada, I get a free massage and a facial.”) He adopts it for himself to gloss over his strained relationship with his parents and dead fiancé. But soon, Marcy appears to be obfuscating troubling details. (“My old boyfriend came over late last night, and yada yada yada … anyway, I’m really tired today.”) Ultimately, George realizes her use of yada yada yada is omitting a fundamental character flaw: a shoplifting habit.

(Oddly enough, Mehlman believed the phrase anti-dentite, which Kramer lobs at Jerry over his concerns about Jerry’s offensive dentist jokes, would be the quotable line of the episode.)

Should you use yada yada yada or add commas (yada, yada, yada)? It probably doesn’t matter, though the former might carry a staccato rhythm more conducive to whatever subject matter you’re trying to obscure. Then again, yada yada yada might be one of those rare everyday phrases meant to be spoken rather than written; its meaning is communicated better in inflection and hand gestures.

Yada yada yada, or something like that.

Have you got a Big Question you'd like us to answer? If so, let us know by emailing us at bigquestions@mentalfloss.com.

Get More Answers to Big Questions: