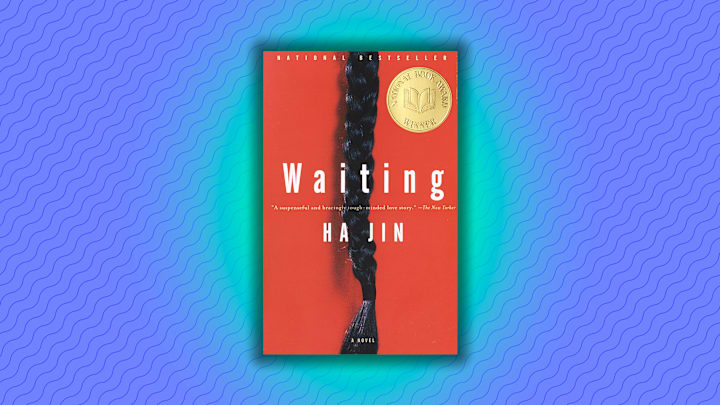

Waiting, Ha Jin’s 1999 novel about a doctor torn between two very different women in a changing China, was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction and won the PEN/Faulkner Prize and the National Book Award for Fiction. “With wisdom, restraint, and empathy for all his characters,” the judges noted, “he vividly reveals the complexities and subtleties of a world and a people we desperately need to know.” Here’s how the book came to be.

- Ha Jin got the idea for Waiting from his wife.

- He wrote the book to keep his academic job.

- Jin was influenced by what he called “European love novels.”

- He lost confidence while writing.

- Critics loved Waiting.

- Waiting is the only book of Jin’s that was published in China.

Ha Jin got the idea for Waiting from his wife.

Jin (whose real name is Xuefei Jin) was visiting his in-laws for the first time when his wife told him the story that would inspire Waiting. As they were leaving the hospital where her parents worked, Jin saw a man from a distance. “My wife mentioned that guy waited 18 years to get a divorce and now the second marriage is not working,” he recalled in an interview with Asia Society. “Later, I joked, ‘This would be good for a novel. I am going to write a novel based on this.’ ”

He wrote the book to keep his academic job.

Though he tried to write Waiting at the time he first heard the story, Jin said he “didn’t have the skills.” He also didn’t really have the interest: “I’d been writing, but not seriously. Even in the States I wasn’t that serious,” he said in an interview with Boston University’s CAS News. “I published a book of poems in English, but I thought I’d return to China to teach American literature—that would be my profession. I was half-hearted.”

That changed when he began teaching at Atlanta’s Emory University. “I had to publish in order to keep my job,” he told Asia Society. “So I think that's why I started writing Waiting in 1994.” The book was initially a novella he published alongside his second book of poetry; when the poetry was later published as a standalone book, he revisited and expanded Waiting.

Jin was influenced by what he called “European love novels.”

In an interview with The Paris Review, Jin called other authors and novels “a source of nourishment,” adding, “With Waiting, I knew I was writing a love novel. So what are the best love novels? Anna Karenina and Madame Bovary—European love novels were behind that book.”

He lost confidence while writing.

In the process of writing Waiting, Jin told The Paris Review, he became convinced that people would not be able to relate to the book. “I wrote so many drafts I got lost,” he said. But that changed when an interview with the wife of a Navy officer. “There was trouble in the marriage and the interview said, ‘Do you think that he’s having an affair?’ And the woman said, ‘Affair? I wish he could have affairs, so that he could prove that he is capable of loving a woman,’” Jin recalled. “At that moment I realized that there were American men like this as well. So I got my confidence back. If Lin had lived in a normal social environment he could have developed into a man capable of having an emotional life or a love life. But his life was so harsh that he suppressed himself and gradually he lost the instinct for love.”

Critics loved Waiting.

Publishers Weekly called Waiting “quiet but absorbing,” while Kirkus Reviews declared it “A deceptively simple tale, written with extraordinary precision and grace.” And John Updike, an award-winning novelist himself, heaped praise on Jin and his second novel in a 2007 piece in The New Yorker. “[Jin’s] prize-winning command of English has a few precedents, notably Conrad and Nabokov, but neither made the leap out of a language as remote from the Indo-European group, in grammar and vocabulary, in scriptural practice and literary tradition, as Mandarin,” he wrote. Waiting, Updike said, was “impeccably written, in a sober prose that does nothing to call attention to itself and yet capably delivers images, characters, sensations, feelings, and even, in a basically oppressive and static situation, bits of comedy and glimpses of natural beauty.”

Author and critic Francine Prose was similarly effusive, writing in her review of the novel in The New York Times that the reader is “immediately engaged by [the novel’s] narrative structure, by its wry humor and by the subtle, startling shifts it produces in our understanding of the characters and their situation. Waiting also generously provides a dual education: a crash course in Chinese society during and since the Cultural Revolution, and a more leisurely but nonetheless compelling exploration of the less exotic terrain that is the human heart.”

Waiting is the only book of Jin’s that was published in China.

After serving in the People’s Liberation Army (he enlisted at 14 and lied about his age), Jin worked at a railroad company, where he learned English. Three years later, he went to college, where he studied American literature and got his master’s. He came to the United States to study in 1985—and watched from afar four years later as the Chinese Army fired on student protestors in Tiananmen Square. He decided to stay in America, and write only in English, publishing poetry and short story collections before releasing his first novel, In the Pond, in 1998, followed by Waiting in 1999.

In 2009, Jin reflected on the choice between writing in Chinese and writing in English. “If I wrote in Chinese, my audience would be in China and I would therefore have to publish there and be at the mercy of its censorship,” he wrote. “To preserve the integrity of my work, I had no choice but to write in English.”

As a result, only one of his novels—Waiting—has been published in his home country (though he noted to The Paris Review that after publishing it “they suspended publication. And what they published, they edited”). “All the other books are banned,” he told GRANTA. “But all my fiction books have been translated into Chinese and published in Taiwan. The readers in the Chinese diaspora can read them.”

Read More About Books: