The rumor spread like wildfire. Richard Stanley, the director of the 1996 science fiction feature The Island of Dr. Moreau, was going to burn down his own film set.

While filmmakers can sometimes be seen as volatile or demanding, few have ever resorted to arson. But Stanley found himself in an untenable position. Moreau, which was to be his entrée into big-budget Hollywood movies, had gone off the rails like few movies ever had. His leading man, Val Kilmer, was allegedly difficult and reportedly even physically abusive to crew; the studio, New Line, wanted to pull the movie in a more commercial direction; bad weather tore through expensive locations, too.

Before it was over, Stanley would be removed from power and find himself in exile as an extra in his own movie.

“Basically,” Stanley told a reporter, “I’m fucked.”

Island Getaway

Stanley, who originally hailed from South Africa, was gifted a copy of The Island of Dr. Moreau by his father when he was a child. Written by H.G. Wells (War of the Worlds, The Invisible Man), the 1896 novel explores a secluded tropical locale where a brilliant yet mad scientist named Moreau does some highly unethical surgery, creating human-animal hybrids that act erratically. A shipwreck drops an Englishman named Edward Prendick into the middle of the madness, where he must confront the consequences of a man playing God.

The book was adapted into two films, including 1932’s Island of Lost Souls—which was banned in many states for boldly proclaiming a belief in evolutionary science—as well as a 1977 version that starred Burt Lancaster as the wayward scientist.

Stanley disliked the latter film, believing it failed to do the Wells novel justice. That lament was never far from his mind as he embarked on a directorial career, one in which he immediately demonstrated a pugnacious understanding of sci-fi and horror: In Hardware (1990), a robot goes berserk. In Dust Devil (1992), a drifter explores occult rituals and leaves supernatural entities in his wake.

These low-budget efforts were critical successes and caught the attention of New Line Cinema, the mid-sized studio behind the Nightmare on Elm Street franchise and, later, the Scream series. In 1992, New Line recruited Stanley, then just 28, for a sprawling adaptation of Moreau backed by a healthy (if not overly generous) $35 million budget.

Stanley’s troubles began early. His adaptation attracted Bruce Willis for the role of an Americanized Edward Prendick, now named Edward Douglas. But Willis bowed out before filming started. New Line then secured a commitment from Val Kilmer, who had risen to prominence in films like 1985’s Real Genius and 1986’s Top Gun before getting a high-profile turn as Batman in 1995’s Batman Forever.

Kilmer was a bankable and sought-after star—and he knew it. After agreeing to play Prendick, he informed Stanley he wanted to work roughly half the days that the role required. That would reduce the script to tatters. Instead, Stanley had Kilmer play a neurosurgeon-slash-security officer named Dr. Montgomery, a smaller role, and hired actor Rob Morrow (Northern Exposure) to play Douglas.

But when Morrow arrived in Queensland, Australia, for filming, he sensed big trouble ahead and reportedly made a frantic phone call to the studio to try and get out of his commitment. (David Thewlis replaced him.)

The shift in roles didn’t placate Kilmer. A 1996 Entertainment Weekly article titled “The Man Hollywood Loves to Hate” portrayed the actor’s behavior on set in a highly unfavorable light, including a report that Kilmer put a lit cigarette to the face of a camera operator. The actor was also criticized by production team members for speaking lines from other roles and showing up as late as 3 p.m. for filming. (Months later, Kilmer would tell The New York Times that Entertainment Weekly had been fed misinformation by vindictive friends of former wife Joanne Whalley-Kilmer, whom he was in the process of divorcing. The Moreau allegations were, he said, “a total lie.”)

Stanley quickly realized Kilmer had a hostile approach to the work. He said the actor refused to rehearse and showed up with character choices out of the blue. “He kept insisting on odd bits and pieces of his wardrobe that didn’t make sense, like a piece of blue material wrapped around his arm,” Stanley said. “It was like, ‘Why is that around his arm, and will he take it off?’ ”

Kilmer’s purported mischief was not Stanley’s only problem. Almost immediately, inclement weather swept away some of the standing sets, prompting shutdowns. According to the director, New Line executives were also unhappy with his focus on the human-animal hybrid creatures (like leopards, pigs, and hyenas), which were being brought to life through extensive prosthetics work and featured a variety of bizarre permutations. Stanley embraced the mayhem of the Wells novel, making Moreau a DNA specialist rather than a surgeon and amping it up with conceits like the baboon hybrids wielding machine guns. The studio, he said, wanted him to shift his focus to the human characters.

It was to little avail. After seeing the dailies, New Line took the radical step of firing Stanley. The director would later say he believed Kilmer deliberately worked to get him removed. However, New Line head Michael DeLuca lamented that the studio hadn’t given Kilmer a “strong director.” Now, it had no director at all.

The film had been shooting less than a week.

Haunting the Set

Had The Island of Dr. Moreau been a mercenary assignment, Stanley might have been able to walk away with only a bruised ego. But the book had been seminal for him, and the adaptation had taken years to develop. He felt emotionally involved and angry; rumors spread he might sooner see the set burn than lose control of it. (That, Stanley later said, was just a joke.) Instead of flying home, he wandered out into the jungle and subsisted on coconuts before returning to the set as a creature extra to observe what might happen in his absence.

Things hardly got better. After 12 days of inactivity, New Line installed veteran John Frankenheimer (The Manchurian Candidate) as the replacement director in the hopes he could better corral the temperamental Kilmer. But Kilmer did little to endear himself to the filmmaker, who swore he would never share a set with the actor again.

“I don’t like Val Kilmer, I don’t like his work ethic, and I don’t want to be associated with him ever again,” Frankenheimer said at the time.

Frankenheimer’s job got tougher with the arrival of an even more difficult performer. While still in control of the production, Stanley had cast Marlon Brando for the pivotal role of Dr. Moreau, sensing the iconic actor’s gravitas could imbue the scientist with a forceful physical and psychological presence.

He could—when he felt like it. Brando employed the actor cliché of refusing to come out of his trailer and insisting his lines be written down rather than have to memorize them. Ron Hutchinson, who was brought on to rewrite the script, later observed Brando was simply bored with making movies and preferred to consume “industrial quantities of pizza” instead.

His Moreau was deeply eccentric—Brando insisted on pancake make-up and flowing smocks. At one point, he placed an ice bucket on his head. The actor, wrote one reviewer, looked like he had been “dipped in egg and rolled around in flour.”

If there was one upside to the chaos of the set, it was in the morbid amusement crew members might take in seeing two equally narcissistic stars face off. At one point, Brando coolly informed Kilmer, “Your problem is, you confuse your talent with the size of your paycheck.”

The Finish Line

Frankenheimer completed the assignment, but the film itself was likely beyond salvaging. The Island of Dr. Moreau made a lowly $28 million at the box office and took a critical drubbing.

The film did have one enduring contribution to pop culture. As part of his unusual approach to the character, Brando insisted that the 2-foot, 8-inch actor Nelson De La Rosa, who was once considered the world’s shortest man by Guinness, play his loyal sidekick. Mike Myers later cited their onscreen dynamic as the inspiration behind the Mini-Me of the Austin Powers films, which New Line also distributed.

“I had just got a DVD player and I was watching The Island of Dr. Moreau,” Myers said. “In this scene, there’s Marlon Brando and this little person and Marlon Brando is playing the piano and on top of the piano is a little miniature version of himself playing a piano … I was like, that would be the one-eighth replica, and I just thought, what if his name was Mini-Me? And instantly I said that to Jay [Roach, the director] and he said, ‘I love this more than anything in life. You’ve just got to give me a week, I’m on a mission to find a guy who can do this!’ ” (They did: Actor Verne Troyer played Mini-Me in two of the films.)

Myers may have been the only one who had benefited from Moreau. Kilmer’s reputation as a difficult actor grew in the years that followed, though he did wind up apologizing to Stanley for how things turned out. It might have rung hollow for Stanley, who didn’t direct another movie until 2020’s Color Out of Space, an adaptation of an H.P. Lovecraft story starring Nicolas Cage.

Frankenheimer arguably fared better. In exchange for the thankless task of trying to salvage Moreau, the director said New Line paid him “a huge amount of money.”

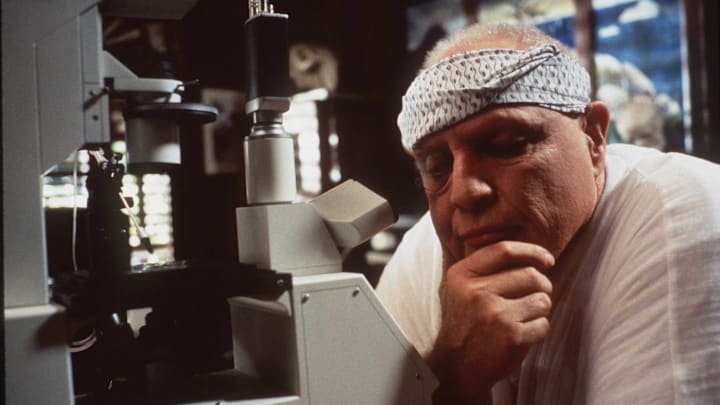

As for the Wells story itself, people haven’t given up on trying to adapt it. As recently as 2020, a television series based on the novel was in development. In 2024, Anthony Hopkins agreed to play Dr. Moreau in a new iteration titled Eyes In the Trees. But that production is already experiencing some tumult: In summer 2024, hackers threatened to release footage of the film unless a $200,000 ransom was paid. As Edward Prendick found out, dropping in on Dr. Moreau always carries a measure of risk.

Read More About Movies: