All maps are influenced by the intent and biases of their creator—even those that are striving to be as accurate as possible. Not only was reliable geographic information harder to come by in past centuries (which has led to some rather odd maps), but there are also plenty of maps that were created with an entirely different purpose in mind, from serving as political propaganda to being deliberately comical. Whatever their reason for existing, here are 20 of the most unusual maps that have been created throughout history.

- Septentrionalium Terrarum

- California as an Island

- Fool’s Cap Map of the World

- Leo Belgicus

- A Map or Chart of the Road of Love

- Britannia

- The French Invasion;—or—John Bull Bombarding the Bum-Boats

- A Map of Mosquitia and the Territory of Poyais

- Sketch of the Coasts of Australia and of the Supposed Entrance of the Great River

- Historical Atlas

- Our Country as Traitors & Tyrants Would Have It; or Map of the Disunited States

- Geographical Fun: Being Humorous Outlines of Various Countries

- The Porcineograph

- Map of the Square and Stationary Earth

- Angling in Troubled Waters

- A Humorous Diplomatic Atlas of Europe and Asia

- Eden in China

- What Would Remain of the Entente

- The New Europe With Lasting Peace

- The Spilhaus Projection

Septentrionalium Terrarum

Flemish cartographer Gerardus Mercator is a big name in the world of mapmaking thanks to creating the Mercator projection, which converts the curvature of the Earth into 2D and became the dominant world map during the 19th century. In the bottom left corner of Mercator’s famous 1569 world map, he included the first known map of the North Pole (which was later published separately under the title Septentrionalium Terrarum). The only problem was that he had no idea what the top of the world actually looked like.

With no intrepid Arctic explorers to question, Mercator turned to a now-lost 14th-century travelogue titled Inventio Fortunata. This fanciful account led the cartographer to place a large black rock—believed to be magnetic—right at the North Pole. The rest of the Arctic is comprised of four chunks of land divided by channels of water, which form a whirlpool around the rock in the center. One of the landmasses is labeled as being home to 4-foot-tall pygmies.

California as an Island

In 1533, Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés landed on what he thought was an island and named it California (he was actually on what is now known as the Baja California peninsula). Just six years later, an expedition led by Francisco de Ulloa proved California was connected to the mainland—but the landmass was still erroneously depicted as an island on many maps for a few centuries. It’s thought this mistake was driven by politics: Sir Francis Drake claimed California for the English in 1579, so Spaniard Antonio de la Acensión said that it was an island to leave the mainland under Spain’s control. It took years to set the record straight; a Japanese map depicted California as a separate entity as late as 1865.

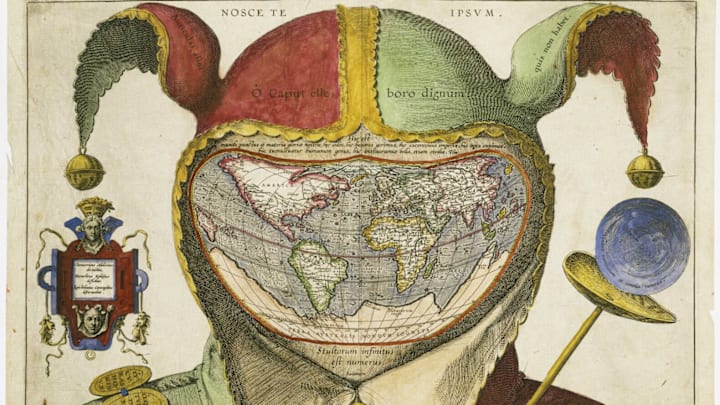

Fool’s Cap Map of the World

The story behind this image of a jester with a world map for a face is a mystery. Because the image matches Ortelius’s oval map projection (which gained prominence 1570s), some believed it dates back to between 1580–1590. Some scholars suspect the mapmaker is Epicthonius Cosmopolites because of the ornate panel on the left-hand side, which declares, “Democritus of Abdera laughed at it, Heraclitus of Ephesus wept over it, Epicthonius Cosmopolites portrayed it.”

Researchers have also theorized about the meaning of the unusual map, with many propsing it’s critical of those who think they have a handle on the world. Not only was a court jester able to openly criticize the monarchy, but the various quotes on the map—including “vanity of vanities, all is vanity” and “the number of fools is infinite” from Ecclesiastes—present a rather cynical view.

Leo Belgicus

During the 16th century, a section of Europe—modern-day Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg—was ready to say goodbye to the rule and heavy taxes imposed by Philip II of Spain. In an effort to give the provinces a united identity to better fight Spain, cartographer Michaël Eytzinger created a fierce map that represented the area as a lion. The 1583 map puts the Dutch city of Groningen in the lion’s snout, Luxembourg sits in the unraised front paw, and the northwest coast of Europe makes up the big cat’s back.

Other mapmakers brought out their own versions of Eytzinger’s Leo Belgicus, which often mirrored political changes as the war for independence waged on. For instance, to reflect the Twelve Years’ Truce, which started in 1609, Claes Janszoon Visscher created a version which depicted the lion peacefully sitting down.

A Map or Chart of the Road of Love

The 1741 erotic novel A Voyage to Lethe, published under the pseudonym Captain Samuel Cock, features an allegorical map of matrimony created by Robert Sayer. Loosely based on the Mediterranean, the map includes directions for romantic travelers: “steering first for Money, Lust, and sometimes Virtue, but many Vessels endeavoring to make the latter are lost in the Whirlpool of Beauty.” Further along the route, in the “Harbour of Marriage,” it is noted that “a good Pilot will also keep clear of the Rocks of Jealousy & Cuckoldom Bay and at least get into that of Content.”

Britannia

James Gillray was well-known for his satirical political cartoons. In 1791, he created a particularly strange anthropomorphic map that styled Great Britain (well, most of it) as an old woman riding backwards on an enormous fish. The Thames Estuary forms the mouth of the fish, Cornwall is its tail, and the tip of the woman’s hat extends into southern Scotland (everything above Edinburgh is omitted). Why exactly Gillray chose to portray the British isle in this way isn’t known.

The French Invasion;—or—John Bull Bombarding the Bum-Boats

John Bull Bombarding the Bum-Boats is another one of Gillray’s cartographic creations, but this one has a clear meaning. The 1793 map crudely and comically expresses the English sentiment toward the possibility of invasion from revolutionary France. England takes the form of King George III—styled as John Bull, a character used in political cartoons as a personification of Great Britain—and he’s blasting feces, labeled the “British Declaration,” onto French boats crossing the English Chanel.

A Map of Mosquitia and the Territory of Poyais

If you’ve never heard of Poyais, there’s a good reason for that: it doesn’t exist. The fictitious country—which was said to be located on the Mosquito Coast between Nicaragua and Honduras—was the invention of Scottish conman Gregor MacGregor.

After having served as a soldier in Central America during the early 19th century, MacGregor returned to Scotland and told people he’d been made the leader of a country called Poyais. He went to great effort to convince people that Poyais was a gold-filled paradise. MacGregor created a guidebook, currency, and, of course, a map. In 1822 and 1823, around 250 settlers sailed to the make-believe country after having bought land from MacGregor. The travelers found nothing there, and almost three-quarters of them died of hunger and disease before rescue arrived.

MacGregor then went to Paris to get the French to buy into his fake country. He managed to evade prison time for fraud after his scam was uncovered and eventually made his way back across the Atlantic to retire in Venezuela with his riches.

Sketch of the Coasts of Australia and of the Supposed Entrance of the Great River

In the late 1820s, East India Company army officer Thomas Maslen became convinced a massive river ran through the Australian outback. After all, other continents have such rivers: South America has the Amazon, Africa has the Nile, and Southeast Asia has the Mekong. In his 1830 book about plans for exploring Australia, Maslen included a map that showed a westward flowing river connecting a huge inland sea to the Indian Ocean. This massive waterway effectively cut the country in half, so Maslen called the northern portion of the country “Australindia” and the southern section “Anglicania.” Of course, exploration of Australia’s interior in later years proved that no such huge geographic feature existed.

Historical Atlas

The maps in Edward Quin’s Historical Atlas (1830) are just as much about what’s not drawn as what is drawn. Each map represents the geographic knowledge of a particular civilization (usually European) at a particular point in history, with dark clouds covering parts of the map that hadn’t yet been explored. The unclouded area of the map slowly grows over time—just a tiny section of Europe and Africa can be seen on the map titled B.C. 753. The Foundation Of Rome, while the eastern coast of America is revealed on A.D. 1498. The Discovery Of America.

Our Country as Traitors & Tyrants Would Have It; or Map of the Disunited States

The Map of the Disunited States, produced in 1864 (toward the end of the American Civil War), shows a version of America that has been divided into four sections. The Confederate States on the map include not only the Southern states that had already seceded from the Union, but also New Mexico, the Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma), West Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware. To the west are the Pacific States (the borderline cuts through Colorado and modern-day Wyoming); to the east (starting at Pennsylvania) is a small group called the Atlantic States; and the rest are part of the Interior States.

The anonymous cartographer’s reasoning behind these divisions isn’t known, but the map also includes a few threatening figures: Napoleon III is handing a crown to Maximilian I of Mexico, a lion wearing a British crown sits in Canada, and a snake guarding a bust of secessionist Vice President John C. Calhoun is pictured off the southeast coast.

Geographical Fun: Being Humorous Outlines of Various Countries

The creative maps in Geographic Fun (1868) were drawn by 15-year-old Lilian Lancaster to entertain her sick brother. Each map is an anthropomorphic reflection of part of a country’s politics or history; for instance, revolutionary leader Guiseppe Garibaldi is depicted in the outline of Italy, with the overthrown Pope Pius IX looking powerless as the small island of Sardinia.

Journalist William Henry Harvey (using the pen name Aleph) wrote both the short rhyming verses below each map and the introduction, in which he explains that the atlas is intended to “excite the mirth of children; the amusement of the moment may lead to the profitable curiosity of youthful students, and embue the mind with a healthful taste for an acquaintance with foreign lands.” How exactly Lancaster and Harvey came to team up is unknown.

The Porcineograph

In 1875, retired sewing-machine magnate William Emerson Baker held a launch party for his “Sanitary Piggery”—essentially a very clean pig farm that was part of his push for stricter food hygiene regulations. (The party was also to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill—Baker was a man of many interests.)

Each of the 2500 guests received a “good-cheer souvenir”: a map of the U.S. in the shape of a pig. Maine is in the snout, Alaska is in the curl of the tail, and the hog’s trotters are Florida and “Lower California” (the Baja California peninsula). The border around the map celebrates pork dishes from each state; Louisiana is represented with its famous gumbo, while California has the rather less familiar meal of bear steak, grapes, and ham sandwiches.

Map of the Square and Stationary Earth

The ancient Greeks were the first to figure out that the Earth is spherical, rather than flat; most people had accepted this fact by the medieval period. But hundreds of years later, Orlando Ferguson still wasn’t convinced. In 1893 he created a Map of the Square and Stationary Earth, which, according to its subtitle, is based on “four hundred passages in the Bible that condemn the Globe Theory, or the Flying Earth.”

Rather than being totally flat, Ferguson envisioned the world to be shaped like a roulette wheel. The Antarctic forms the edge of the world, beyond which are four angels, which aligns with Revelation 7:1: “four angels standing at the four corners of the earth, holding back the four winds.” And to demonstrate his derision for the accepted scientific view, on the right-hand side he also included an image of two men struggling to hold onto a spinning spherical Earth.

Angling in Troubled Waters

Angling in Troubled Waters, created by world-famous satirical mapmaker Fred W. Rose, is a cartographical caricature of Europe’s political state in 1899. A colossal Czar Nicolas II of Russia has his boots planted on Turkey and Eastern Europe. Colonies are depicted as fish: France is struggling to hold onto its catch because of the Dreyfus affair; Britain smiles at having Ireland in a net over its shoulder and an Egyptian crocodile on the line; and Spain looks on as its territories are snatched by an off-map America following the Spanish–American War.

A Humorous Diplomatic Atlas of Europe and Asia

In 1877, Fred W. Rose created a map to reflect the recent Russo-Turkish War, with Russia portrayed as a massive octopus whose tentacles are stretching out over Europe. Kisaburō Ohara, a student at Keio University in Tokyo, expanded Rose’s map in 1904 to demonstrate Russia’s ambitions in Asia. A text box in the upper left corner references the recent Battle of Port Arthur in Manchuria (modern-day northeast China): “the black octopus is so avaricious, that he stretches out his eight arms in all directions, and seizes up everything that comes within his reach. But as it sometimes happens he gets wounded seriously even by a small fish, owing to his too much covetousness.”

Eden in China

When it comes to placing the Biblical Garden of Eden on real world maps, many people point to the Middle East, but other locations have been suggested. For instance, Tse Tsan-tai believed the religious paradise could actually be found in China. Tse, an anti-Qing dynasty revolutionary and co-founder of the South China Morning Post, developed this theory to argue that Christianity in China was not a tool of the West (being openly Christian in China at the start of the 20th century could be deadly). Leaning on the description given in Genesis—which states that Eden is the source of four rivers—Tse drew up a map in 1914 that placed the garden in Chinese Turkestan (modern-day Xinjiang).

What Would Remain of the Entente

The propaganda maps created during World War I typically focus on Europe, but one German map took things worldwide. What Would Remain of the Entente was created in response to President Woodrow Wilson’s statement about countries having self-determination: “National aspirations must be respected; people may now be dominated and governed only by their own consent.”

This 1918 map points out the hypocrisy of this argument (and uses it to wrongly justify Germany’s invasion of surrounding countries) by highlighting the territories the Allied Powers had previously denied self-determination. America, Britain, France, and Russia are overlaid with a person holding the reins of symbolic animals—bison, lion, cockerel, and bear, respectively—that are placed on the countries under their control.

The New Europe With Lasting Peace

In 1920, an author using the pseudonym P.A.M. published a pamphlet outlining their idea for ensuring peace in Europe shortly after the end of World War I. Alongside this pamphlet—which recommended the adoption of a communal currency, time zone, and language—P.A.M. included a map that illustrated their plan for ending disputes between countries. With St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna serving as the central point, much of Europe would be sliced into equally-sized pie-shaped canton wedges. Not all countries got a slice of the pie, though, with Spain, Portugal, Italy, Greece, the UK, and the Nordics being left out.

The Spilhaus Projection

The vast majority of maps are drawn to prioritize land, but geophysicist and oceanographer Athelstan Spilhaus—who helped create the secret weather balloon that was mistaken for a UFO when it crashed in Roswell, New Mexico, in 1947—designed a map that instead focused on the world’s water. Centered on Antarctica, the map shows the Earth’s oceans as an uninterrupted body of water. Australia, Africa, and Europe are whole; Asia and America are stretched along their coasts.

Spilhaus first discussed his idea for an ocean projection in 1942. But it wasn’t until 1979 that the map—created with the help of geodesists Robert Hanson and Erwin Schmid—made its debut in a Smithsonian article. “The distortions at the two corners around the poles in South America and China are very great indeed,” Spilhaus admitted, “but it is in the land that we wish to concentrate maximum distortions.”

Discover More Fascinating Maps: