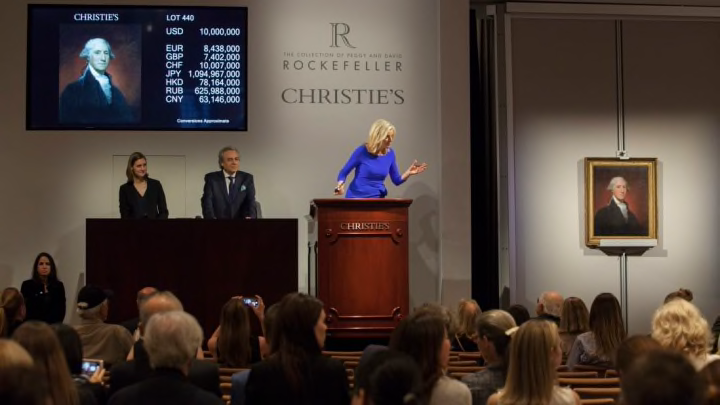

If a fine art auction can be compared to a well-coordinated circus, then the auctioneer is its ringmaster. At any given auction—which may include hundreds of people in the room and hundreds more watching online—the auctioneer is center stage, directing the audience's attention to lots big and small, generating excitement, and making sure the bidding runs smoothly. Auctioneers manage "all this while having charisma and a sense of engagement and great energy,” says Tash Perrin, an auctioneer who also holds a couple of senior management titles at Christie’s auction house. To find out what it takes to perform in such a fast-paced setting (and whether they always talk the way you see in the movies), we spoke with three New York City-based auctioneers who work for some of the world’s largest auction houses: Christie’s, Phillips, and Bonhams.

1. Auctioneering is mostly a side gig.

At the big auction houses, practically no one is hired to work solely as an auctioneer. As Perrin explains, “Nobody here at Christie’s is an auctioneer full-time. All of us have full-time jobs and then we do the auctioneering as a side gig.” Some auctioneers manage a particular department within an auction house, while others work in a variety of roles that may take advantage of their specialty in a particular field, whether that’s Chinese ceramics, Islamic art, or jewelry.

As a specialist in postwar and contemporary art with Bonhams, for example, Jacqueline Towers-Perkins sources all of the artworks for auction, researches their origin, and makes sure they’re authentic (and not some knock-off). Finally, as an auctioneer, she gets to find a new home for them. “When it comes to selling [an artwork], that is sort of the icing on the cake,” she tells Mental Floss.

2. Auctioneers need to be licensed in some states.

More than half of all U.S. states stipulate that individual auctioneers must get a license before selling items at public auctions. New York state does not have such a law, but leaves the decision up to individual municipalities. New York City—the location of many big-name auction houses—does mandate it. Would-be auctioneers must go to the Department of Consumer Affairs—“the same place that hot dog vendors get their license,” Perrin says.

3. Not all auctioneers speak quickly.

If you’ve been picturing an auctioneer who talks a mile a minute, you’re probably thinking of cattle auctioneers, who rattle off increments in an almost meditative style called "chanting." A few other types of auctioneers talk this way, but you won’t hear it at any of the major art and antiquities auction houses, which also sell across categories including jewelry, handbags, watches, wine and spirits, books and manuscripts, and more.

That’s because an auctioneer’s cadence largely depends on what they’re selling. Speed is especially important for cattle auctioneers because they often have more lots (a.k.a. individual cattle) to sell than the typical art auctioneer. (They also talk that way to "hypnotize" bidders, according to Slate.) However, when it comes to prized artworks and rare artifacts that rack up millions of dollars at auction, an auctioneer’s goal is slightly different: to generate excitement and build suspense. Sometimes, they might even slow down and allow a moment of silence to fill the room before speeding up again. “A really important element to being a good auctioneer is your ability to speak silence,” Perrin says. That means allowing for pauses when necessary—such as when a potential buyer might be thinking about a bid. It’s also about creating a welcoming atmosphere for bidders. “We want this to be a really great environment ... We don’t want to rush people through it or make it intimidating," Towers-Perkins adds.

4. Auctioneers sometimes stick out their tongues and recite Humpty Dumpty as a vocal warm-up.

Because auctioneers are talking non-stop for several hours at a time, the vocal warm-ups they do before an auction can get pretty ... creative. “Reciting Humpty Dumpty with your tongue out is definitely something we would encourage,” says Perrin, who also coaches auctioneers-in-training. In the above video from The New York Times, Christie’s former head of auctioneering, Hugh Edmeades, can be seen reciting this nursery rhyme to loosen up his facial muscles and warm up his voice. Perrin says some auctioneers might also recite their increments (we’ll get to those later) in the shower before coming to work, while others might use breathing and vocal techniques that are similar to the ones employed by actors and singers.

5. The auctioneer’s book is their bible.

Auctioneers can glean everything they need to know about a sale from something called the “auctioneer’s book”—although at some auction houses, it's a digital file on a laptop rather than a physical book. The book contains the lot number (the identifying number of the item or group of items up for sale), the item’s description, and the amount of money it’s expected to go for. It also has one crucial piece of information that neither the bidder nor the general public gets to see: The reserve price. This is the amount of money the owner of the lot will—or will not—sell it for.

6. An auctioneer's ability to multitask is crucial.

Juggling multiple tasks at once is a skill auctioneers must learn to master. In addition to remaining aware of the reserve price, auctioneers must also check their book for any absentee bids that have been placed prior to the sale. Bids are also coming in over the phone and online, and those bidders must be given the same attention and opportunity that bidders in the room are afforded. Throughout all this, auctioneers have to be engaging and charismatic. “If it looks like you’re very methodical and have a sense of just trying to get the job done, you’re not engaging the audience,” Perrin says.

While auctioneers are on the hook for most of the sales proceedings, they do get some help from a bid clerk. This person stands next to the auctioneer and surveys the room—including the phone bank, where staff talk to potential buyers over the phone and hold up a paddle whenever a bid comes through—to catch bids the auctioneer might not have seen. This extra assistance is especially helpful when there are 700 or so bidders in one space. “They play an incredibly important role, and I often refer to them as my best man up there,” Perrin says.

7. There’s a lot of math involved in auctioneering.

Auctioneers can only use certain increments, which means they’re limited in the exact price they can offer to bidders. “It’s very set,” Towers-Perkins says. “The numbers go up in tens at the beginning, then in twenties, then in fifties, then in hundreds.” (The precise numbers can vary by house.) This gets all the more confusing when absentee bids are factored into the equation. Auctioneers must ensure they’re referring to the exact amount declared in an absentee bid, which means they must think ahead and do a bit of quick math to figure out which number they should call out. Perrin calls this skill “numerical dexterity,” but there’s another term for it too. When everything goes well and auctioneers offer the correct increments, it’s called “landing on the right foot.” (And when things go wrong, it's called, naturally, landing on the wrong foot.)

8. Auctioneers can tell the difference between an involuntary nod and a bid.

Sometimes, a nod is just a nod. Other times, it’s a bid. Auctioneers are trained to observe bidders’ body behavior and know the difference. Customers usually raise their paddles to place a bid, but some might prefer to remain discreet. Sarah Krueger, an auctioneer and head of the photographs department at the New York City branch of Phillips, said auctioneers get to know the bidding styles of frequent clients: “A nod or a slight move might indicate a bid from one person, but for another they might just be waving at a friend across the room.” Perrin says one client in England bids by raising his eyebrows, while other bidders wink to raise the stakes. Usually, an auctioneer can judge whether or not a bid is intentional by paying attention to the bidder’s level of engagement—for instance, if they’re looking at the auctioneer or still have a paddle in their hand, they’re probably interested.

9. They take their gavels seriously.

Krueger has her own personal collection of six gavels: Three of them she uses in auctions, while the other three are more like collector’s items. Each auctioneer has their own preferences in terms of the style of gavel they use. “For my purposes, what I’m looking for in a gavel is something that fits comfortably in my hand and isn’t too heavy,” she says. “You also want to test it out against your sounding block and make sure that it’s giving you the right sound.” After all, auctioneers say that the moment the hammer falls, signifying the end of a sale, is one of the most enjoyable parts of the job. “The sound the gavel makes on the rostrum is incredibly satisfying—particularly on the very first lot you ever take and the most expensive lot you’ve ever sold,” Perrin says. “That’s extremely gratifying.”