In 1967, the arrival of Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde signaled a sea change in cinema—one in which a group of young, visionary directors wrested power from the studio executives who had long guarded the gates to Hollywood. Out went the overproduced feelgood films that had defined the movies for decades; in came an onslaught of counterculture-leaning features that didn’t shy away from frank depictions of sex and violence and leaned into the disillusionment felt as a result of the Vietnam War and America’s tense political climate. It was an era called “New Hollywood,” and writer/director Robert Altman was among the movement’s most celebrated directors.

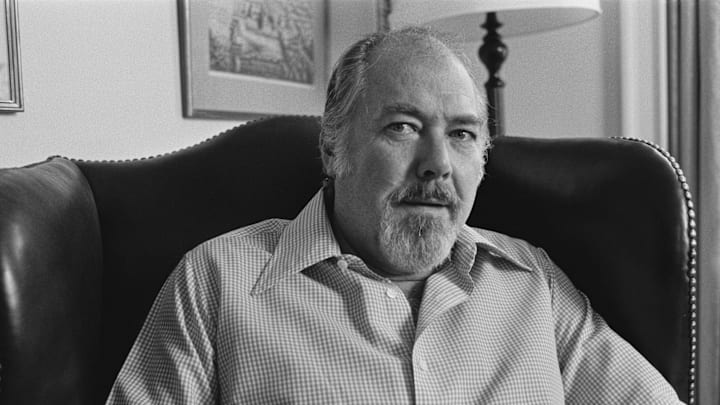

In recognition of what would have been the Oscar-nominated filmmaker’s 100th birthday (he was born in Kansas City, Missouri, on February 20, 1925), here are some fascinating facts about the auteur who made both Popeye and A Prairie Home Companion.

- He tattooed Harry S. Truman’s dog.

- Altman got his start in industrial films, which is where he learned to appreciate his actors.

- Altman partly owes his career to Alfred Hitchcock.

- M*A*S*H made Altman a household name.

- Altman helped deliver Hollywood’s first on-screen F-bomb.

- He was far from the first choice to direct M*A*S*H.

- Altman wasn’t a fan of scripts.

- He wasn’t interested in making big-budget pictures.

- His movie Nashville still holds a Golden Globe record.

- Altman gave Arnold Schwarzenegger one of his earliest roles.

- He designed a Swatch watch.

- Altman had no regrets about making Popeye.

- He had some harsh words for James Cameron.

- Paul Thomas Anderson was Altman’s in-case-of-emergency director on A Prairie Home Companion.

- He refused to pick a favorite of his films.

He tattooed Harry S. Truman’s dog.

After graduating from high school, Robert Altman spent three years as a first lieutenant in the Army Air Corps, where he served as a B-24 co-pilot during World War II. He left the military in 1947, returned to Kansas City, and began looking for work. As he recounts in Mitchell Zuckoff’s Robert Altman: The Oral Biography, the future filmmaker took a stab at the entrepreneur thing when he and two other men attempted to launch a pet tattooing business known as Identi-Code. Like today’s microchips, the point of the tattoos was to create a permanent record of a pet’s owner in case a cat or dog went missing.

“We would shave the area on the inside of the right hind leg, up near the groin … then I would write in these numbers,” Altman recalled. Though the company did not find much success, they did manage to land one prominent client: then-president Harry S. Truman. “Truman had this dog he didn’t even care about, a little dog of some kind,” Altman told Zuckoff. “They sent it over to us and we tattooed it.”

Altman got his start in industrial films, which is where he learned to appreciate his actors.

When the pet tattoo business went bust, Altman was forced to look for alternative employment. He managed to land a job at the Calvin Company—a now-defunct industrial film producer—despite having no previous filmmaking experience. It’s there that Altman learned the basics of filmmaking, and began to appreciate just how essential the right actors were to the process.

“At first I was in awe of actors, and then I came to love actors,” Altman told Chicago Magazine in 2001. “I came to sort of understand how really courageous they are. They’re the ones that stand up there naked. It’s not me. It really is an actor’s medium.”

Altman partly owes his career to Alfred Hitchcock.

In 1957, Altman wrote and directed The Delinquents, about a teenage boy who joins a gang after his girlfriend breaks up with him. The film was ultimately seen by Alfred Hitchcock, who was so impressed that he recruited Altman to direct two episodes of the anthology series Alfred Hitchcock Presents: “The Young One” and “Together” for Season 3. These projects brought Altman even further recognition, leading to more directing jobs.

M*A*S*H made Altman a household name.

Though the New Hollywood movement was already three years into being when Altman’s M*A*S*H arrived in theaters, it was deemed revolutionary. The director’s freewheeling style—often shooting with multiple cameras while actors, each outfitted with tiny microphones, improvise in character, unaware which takes might make the final cut—gave the film a naturalistic quality that had rarely been seen before. Even more jarring was the way that dialogue was delivered: Instead of one character speaking at a time, Altman’s characters spoke over each other—again, imitating real life versus the manufactured Hollywood version of the way people converse. It was a technique that quickly became a hallmark of Altman’s films, making them instantly recognizable to audiences.

When Altman employed the technique again the following year on his revisionist western McCabe & Mrs. Miller, celebrated cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond expressed concern. “I don’t understand what the people in the background are saying,” the DP informed his director. “Well, Vilmos, you’ve been in noisy bars,” Altman responded. “Do you hear what those people are talking about in the background? I want a soundtrack which is real. Sometimes you don’t understand what they are saying.”

Altman helped deliver Hollywood’s first on-screen F-bomb.

A funny thing happens when you keep your cameras running and don’t give your actors a script to read from: They sometimes say things a screenwriter might never have put into their script. That’s what happened on the set of M*A*S*H, which is widely considered the first mainstream movie in which the word f**k is uttered.

He was far from the first choice to direct M*A*S*H.

In many ways, Altman owed his storied to career to the many, many directors who said “no” when offered the chance to direct M*A*S*H. Though the exact number of people who passed on the project is in contention, most sources—including The New York Times—claim that a total of 15 directors were offered the directing gig before Altman.

Altman wasn’t a fan of scripts.

Actors who signed up to work with Altman quickly learned his many creative quirks, including his indifference toward carefully constructed screenplays. For the director, a film set was a collaborative atmosphere where everyone—especially the actors—was expected to learn the basic setup of the story they were attempting to tell, then inhabit their parts, dialogue and all. Which didn’t always make for happy screenwriters. “I get a lot of flak from writers,” Altman told TIME in 1992, as The Player was arriving in theaters. “But I don’t think screenplay writing is the same as writing—I mean, I think it’s blueprinting.”

Case in point: M*A*S*H was awarded the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay in 1971—though screenwriter Ring Lardner Jr., who accepted the statuette, didn’t seem so sure the accolade was accurate. After a screening of the movie, he approached Elliott Gould, one of the film’s stars, and said, “There’s not a word that I wrote on screen.”

He wasn’t interested in making big-budget pictures.

Following the success of M*A*S*H, which was nominated for five Oscars, Altman became one of Hollywood’s most in-demand directors and had his pick of scripts. “I was being offered big, big movies,” Altman said. “I said I didn’t want to make anything like that. I took a really low-budget project instead. I’ve done that all my life. If something works for you, you continue to do it. I did a bunch of pictures for 20th Century Fox when Alan Ladd was over there, but I set the budgets so low that they’d approve and I’d deliver the film. They would have no say in it, which is the kind of arrangement I liked.”

His movie Nashville still holds a Golden Globe record.

For many critics and fans alike, Altman’s 1975 country music ensemble Nashville remains his crowning achievement. The epic ensemble won a slew of awards, including an Oscar for Best Original Song for Keith Carradine’s “I’m Easy.” But one of its crowning achievements was being nominated for a record-setting 11 Golden Globe Awards—the most nominations ever received by a single movie. Today, 50 years later, that record still stands.

Altman gave Arnold Schwarzenegger one of his earliest roles.

In 1973, Arnold Schwarzenegger made his second-ever movie appearance in an uncredited role in The Long Goodbye. Schwarzenegger was brought to Altman’s attention by David Arkin, another actor in the film. When casting for the uncredited role of “Hood,” Arkin told Altman, “ ‘I got a friend, a guy I just met and he looks terrific. He's got the damnedest muscles you've ever seen.’ And I said, well, fine, bring him along. We’ll use him as one of the guys,” Altman told ScreenTalks. “Arnold doesn’t talk about that film. He doesn’t remember that film. But I like him. Arnold is terrific.”

He designed a Swatch watch.

In 1995, Altman was chosen by the executives at Swatch to design a “Time to Reflect” watch to celebrate 100 years of cinema. If you’re looking to find one, there are plenty to be found online on places like eBay, Poshmark, and Etsy. Prices range from $50 to $300, depending on its condition.

Altman had no regrets about making Popeye.

Following the success of movies like Star Wars and Jaws toward the end of the New Hollywood era, blockbusters became the goal for studios—and some filmmakers. Though Altman professed not to be interested in making a big-budget movie, he took a chance in 1980—following a string of flops—and agreed to direct a big-screen, musical adaptation of Popeye starring Robin Williams. Though the production was riddled with problems and the initial reviews were largely negative, Altman had no regrets about making the film. When asked by Chicago Magazine whether experiences like Popeye made him consider quitting Hollywood altogether, Altman’s response was emphatic: “No, because it’s too much fun. It’s like giving up sex. You don’t do it for very long. You are discouraged, but basically you come back and say, ‘I wanna do that again.’ ”

For the record, Popeye was not the box office bomb it has regularly been painted as. The film, which was shot on a budget of $20 million, brought in approximately $50 million at the global box office. For fans of the movie: much of the set, which was built in Malta, still exists today.

He had some harsh words for James Cameron.

Altman was famously forthright with his opinions on just about every topic, including his fellow filmmakers. In a 2000 chat with The A.V. Club, interviewer Keith Phipps mentioned how James Cameron had written a letter to the Los Angeles Times suggesting that renowned film critic Kenneth Turan should be fired for writing a negative review of Titanic. Altman’s immediate response: “James Cameron, can he write?”

“He should get a negative review,” Altman continued. “It was a sh*tty picture. For him to criticize anybody for what they say about that picture proves he’s as crazy as he advertises.”

Paul Thomas Anderson was Altman’s in-case-of-emergency director on A Prairie Home Companion.

Ever since Boogie Nights, critics have regularly compared the work of Paul Thomas Anderson to that of Altman—and Altman was an admitted fan of the 11-time Oscar nominee. So it was befitting, and a comfort to Altman, that when he was directing his final film, A Prairie Home Companion, Anderson was on set to step in as director should anything happen to Altman.

“He was with me all the time,” Altman said of Anderson. “He’s a good friend of mine. I’m 80 years old, so they don’t insure me. On Gosford Park, which was the first time I did this, Stephen Frears was my stand-in. That’s all an insurance issue. I’ve known Paul since he started, and he’s always been very generous about the origins of his work. Paul agreed to do it, which surprised and thrilled me. His girlfriend, Maya Rudolph, who was pregnant, was in the film as well. So that made things easier. It worked out well.”

He refused to pick a favorite of his films.

Though fans generally have no problem choosing a favorite Altman movie, the filmmaker himself could not do the same. When asked by The A.V. Club if he agreed with the common consensus that Nashville was his best movie, Altman said that, “I like ’em all. They’re like children, you know, and you tend to love your least successful children the most. But I don’t think there’s a best any more than … I don't think things are best. In terms of my own assessment of my work, it’s no better than any others.”

Discover More Fascinating Stories About Entertainment: