The 19th and 20th centuries were rife with upheaval. In the 1800s, slavery still existed in many parts of the world; Europe was in political and social chaos, from the Napoleonic Wars in the beginning of the century to the Russian Flu by the end of it; and many countries were fighting for independence from colonial powers. With the 1900s came the abolition of slavery in some countries and freedom for many colonized nations, but also other massive world-changing events, from the First World War and the Great Depression to the Second World War and the Cold War, along with everything in between.

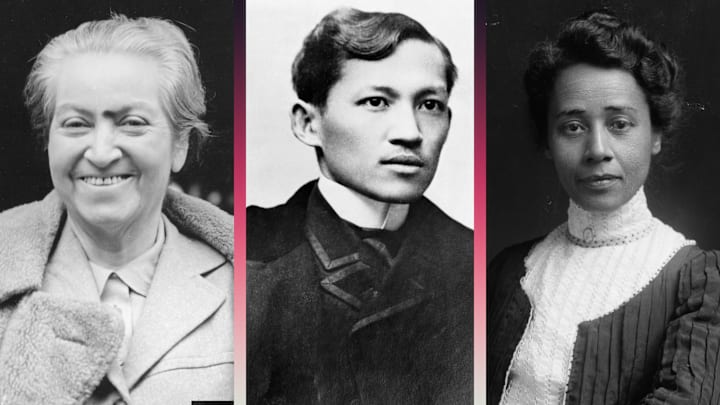

Amid the chaos, writers of color emerged whose work was so powerful and influential that they transformed their home countries—but though their contributions were immense, many aren’t well-known outside of their nations’ borders. Here are six who deserve more recognition.

1. Eugenio María de Hostos (1839-1903)

Eugenio María de Hostos was a Puerto Rican writer, educator, and advocate who supported the liberation of the Dominican Republic (which was controlled by Spain in 1863), Cuba, and Puerto Rico from Spanish colonial rule. His father actually worked for Queen Isabella II of Spain, and in 1852, Hostos was sent by his parents to study in Bilbao. A few years later, he went on with his studies in Madrid, where he became interested in politics. His most famous work, La peregrinación de Bayoán, was published there in 1863; the novel is written in diary form and manages to romanticize the three colonies while also describing their mutual suffering from Spanish colonization.

Hostos left Spain after the country refused to grant Puerto Rico self-governance in 1869; he went to the United States and became editor of La Revolución, a newspaper devoted to Cuban independence. He spent the rest of his life working to liberate Spain’s Caribbean colonies and used journalism, plays, and books as a space to contest colonization and influence revolution.

Cuba and the Dominican Republic eventually became independent, but Puerto Rico did not—after the Spanish American War, ownership went to the United States. Although Hostos’s goal of total independence for all three colonies wasn’t achieved, he still managed, among other things, to transform the conversation around Caribbean identity and politics.

2. Anna J. Cooper (1858-1964)

Born into slavery in North Carolina in 1858, Anna J. Cooper became a writer, educator, and activist whose 1892 book, A Voice from the South by a Black Woman of the South, has led her to be dubbed the “Mother of Black Feminism.”

In addition to getting both a bachelor’s and master’s degree in mathematics, Cooper was the fourth Black American woman to receive a Ph.D. (she studied history at the University of Paris, Sorbonne, graduating in 1925). She also contributed in the field of sociology, arguing, in the words of the National Park Service, “that Black women had a unique standpoint from which to observe and contribute to society,” and advocating that educating Black women would make them “at once both the lever and the fulcrum for uplifting the race,” she explained in A Voice From the South.

Cooper was a pioneer in speaking about intersectionality before the term even existed (it was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989), influencing future thought, theory, and praxis around equal rights for Black women and the distinctive issues that affect them.

3. Jacques Stephen Alexis (1922-1961)

It makes sense that Haitian novelist, intellectual, and advocate Jacques Stephen Alexis would enact change—he was a descendant of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, one of the leaders of the Haitian Revolution, and the son of Stephen Alexis, who was Haiti’s ambassador in the UK, representative of Haiti in the United Nations, and author of an important biography of the great Haitian general Toussaint Louverture.

Influenced by this rich lineage, Alexis published his first writing, an essay, at the age of 18 to great acclaim. In his novels, which include Compere Général Soleil (General Sun, My Brother, 1955) and L‘Espace d’un cillement (In the Flicker of an Eyelid, 1959), he not only defended the poor but contextualized them, their realities, and their experiences, and called for the unity of all Haitians regardless of class.

As a communist, Alexis’s works accompanied and were motivated by his political work. He created a left-wing political group in 1959, which led to his exile by Haiti’s then-President François Duvalier soon after. He secretly returned to Haiti in 1961, was captured, and consequently killed.

Alexis’s writings influenced the contemporary Haitian writer Edwidge Danticat, who is one of today’s leading voices for Haitian immigrants and their experiences.

4. José Rizal (1861-1896)

The writings of this Filipino polymath (who studied medicine, philosophy, and languages) helped inspire the movement that led the country to colonial freedom from Spain (though he technically advocated reform of Spanish rule, not immediate freedom from it). Rizal moved to Europe to continue his education in 1882, and finished his first novel, Noli Me Tángere—a brutally honest account of the atrocities of Spanish colonization in the Philippines—while living in Berlin. The novel was published in 1887 and quickly banned in the Philippines. After briefly returning to Manila that same year to an antagonistic atmosphere (Rizal was even shadowed by police), he decided to leave once again. He published his second novel, El Filibusterismo, an extension of Noli but with an increased revolutionary approach, in 1891. This book barely reached the Philippines, and any copies that did were burned.

Rizal continued to write about the Filipino experience during colonial times in everything from poetry to plays, and he advocated for social reforms to grant Filipino people a voice within the colonial structure. He formed La Liga Filipina in 1892, an organization whose objective was to directly include people in the legal reform process; this political activity led to his internal exile. Eventually, he left to work as an army doctor in Cuba, but en route, he was sent back to Manila to be tried on a charge of sedition. He was executed in 1896.

Liberation from Spain ultimately occurred in 1898, but the country wasn’t free: It was taken over by the United States. The Philippines didn’t gain full independence until 1946. A decade later, a law was passed in the Philippines requiring students at most universities to take courses on Rizal.

5. Forugh Farrokhzad (1934/5-1967)

Born in Tehran, Iran, to a strict military father and a mother who was a housewife, Forugh (also Forough) Farrokhzad began writing poetry at a young age—but she immediately destroyed her poems out of fear that her father would find them. Women at this time were expected to fulfill conventional gender roles by taking care of the household and the family; they were not encouraged to be thinkers.

Farrokhzad became a housewife herself at the age of 16 when she married a much older man, but continued to write whenever she completed her housework. She published her first poetry collection, The Captive, in 1955. One poem, “Sin,” was published in a literary magazine alongside a photo, a biography, and under her real name—all unusual for an Iranian poet of any gender at that time.

Farrokhzad’s poems were divisive because of their erotic tones; she received mixed reviews but also gained recognition from them. There were other consequences, too: “Sin” openly acknowledged that she had had an affair while married; according to The Paris Review, while men could have as many affairs as they pleased, “an adulterous woman was taking her life into her hands—she could be killed for her transgression and her killers barely punished.” Farrokhzad wasn’t killed, but when she divorced her husband, she lost custody to her son, Kamyar.

Farrokhzad continued to write about the intimate world of women and directed a documentary before her untimely death in a car accident at the age of 32. She is still praised today for advocating for women and their freedom.

6. Gabriela Mistral (1889-1957)

The Chilean poet and diplomat who would become the first Latin American writer to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature was born Lucila Godoy Alcayaga in Vicuña, Chile, in 1889, and raised in the small village of Monte Grande.

She initially found inspiration close to home: Mistral’s father (who pretty much abandoned the family when she was young) was a poet and teacher, and her religious grandmother was a lover of literature and poems. But it wasn’t until she left Monte Grande at age 11 to study in Vicuña that she began to write about the hardships she experienced away from home, as well as the realities that women, children, and the poor (whom she advocated for throughout her life) faced in the world. For her writings—which included newspaper articles, short stories, and poems—she used a penname that was probably assembled from the monikers of two other poets (though another theory has it that the name came from the archangel Gabriel and a French wind [PDF]).

Poems like Poemas de la madre más triste, inspired by the abuse of Indigenous people, garnered her recognition, but it was works like Desolación, Sonetos de la Muerte, and Ternura that made her legacy. Mistral’s works greatly impacted conversations about femininity, motherhood, and other societal issues at a time when women were not expected to speak about such things.