In today’s world, the world of tomorrow is usually showcased at events like the Consumer Electronics Show (CES), or via grand announcements from companies like Apple. But in the 19th and 20th centuries, technological and architectural marvels often debuted at world’s fairs. The Eiffel Tower, the X-ray machine, and even IMAX movies were all initially seen by enraptured attendees at these massive gatherings that attracted attention from around the globe. Some have described them as “architectural beauty pageants.”

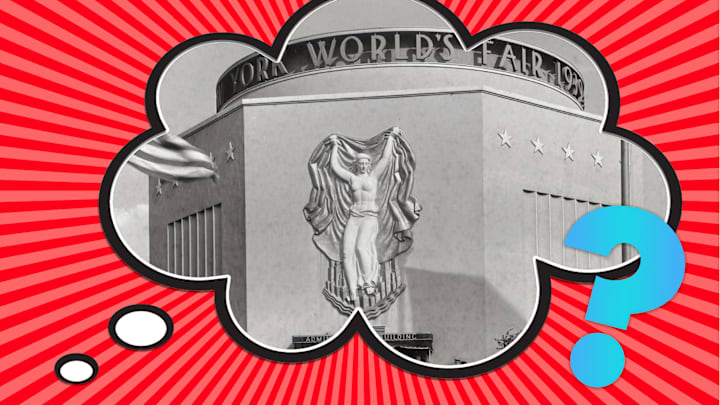

Yet no world’s fair has made much of an impression on Americans since the 1964-65 event in New York City, which popularized the Belgian waffle and showcased color televisions from RCA. Subsequent affairs in the late 20th century failed to capture attention. The last one in the U.S., in 1984, lost millions. So why don’t we see world’s fairs or expos anymore?

As historian Grant Wong writes in Smithsonian, it’s not that the fairs changed: It’s that visitors did. Before the internet, satellite television, and sophisticated entertainment, a world’s fair was a place to get a glimpse into the future and to experience another—usually better—quality of life. Today, a person can have that experience merely by browsing a tech site online, visiting a theme park, or heading to a Best Buy.

That now-abandoned sense of wonderment was strong in 1851, when the Great Exhibition took place in London and showcased a variety of industrial achievements inside the Crystal Palace, a glass-walled structure that stood as an attraction even after the event ended. (It hosted the world’s first scale dinosaur models.) Later, events like Century 21 in Seattle in 1962 went even further, giving the public its first glance at the Space Needle.

Often, these attractions lived up to the “world” part of their name by offering the ingenuity from countries around the globe. Where else could an average American see how the Czechs lived, or what Japan was up to? It was a way to exchange ideas, but also a way to boast. That, too, largely fell by the wayside as the Olympic Games rose in popularity in the 20th century and the U.S. turned toward physical rather than creative sparring on an international scale.

For America, nationalism in architecture and technology largely became moot when the Cold War fizzled in the 1980s, and the country was no longer engaged in a battle of one-upmanship with the Soviet Union. The 1984 world's fair celebration in New Orleans led to $100 million in debt thanks to sparse attendance: just over 9 million people visited compared to the 15 million expected. It was the first time there was speculation the fairs had become passé, and the last time one was held in the U.S.

In 1998, Congress dissolved the United States Information Agency, which was responsible for American participation in such events. Combine that with the financial losses suffered by host cities and it’s little wonder no one stateside has been eager to mount a world’s fair. (The last one in North America was in Vancouver in 1986, which was introduced by Prince Charles and Princess Diana.)

While the concept may have run out of gas in the U.S., it’s still very much alive in other parts of the world. Shanghai hosted a successful event in 2010; Dubai saw 24 million visitors in 2022. And while the U.S. does attempt to have some sort of presence in such events via corporate efforts, the results are often criticized as meager. In Shanghai, the U.S. pavilion was compared to a shopping mall, and not favorably. (It was also designed by a Canadian.)

But there may be hope. Presidents—including Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden—have all endorsed a U.S. resurgence into expo territory. Minnesota is campaigning to host a 2027 specialized expo, but smaller in scale and duration than previous fairs, and with an ecological theme. The site is set to be decided in June 2023.

Have you got a Big Question you'd like us to answer? If so, let us know by emailing bigquestions@mentalfloss.com.