Père-Lachaise is Paris’s largest and most eminent cemetery, a historic place of reverence where visitors pay their respects to the likes of Marcel Proust, Édith Piaf, Jim Morrison, and Molière.

It’s also where people give Victor Noir’s bronze crotch a good rub.

The practice purportedly improves your fertility or at least brings you luck in love, and it’s such a popular one that officials once banned it to protect the effigy from damage (the bourgeoisie revolted).

But before Noir became Père-Lachaise’s patron saint of sex, he was famous for something else: getting murdered.

Duel of the Faits

In 1869, while Emperor Napoleon III (Napoleon I’s nephew) struggled to both liberalize France and expand its power abroad, two Corsican newspapers—the radical left’s la Ravanche and the conservative, Paris-based l’Avenir de la Corse—were arguing over whether he was doing a good job.

The emperor’s cousin, Pierre-Napoléon Bonaparte, took umbrage at la Ravanche’s censure of his family and wrote a searing letter to its rival paper in which he called la Ravanche’s writers “cowardly Judases … whose own relatives in earlier days would have put them in bags and tossed them into the sea.” L’Avenir published this takedown on December 30, which garnered a rejoinder from la Ravanche’s Parisian affiliate la Marseillaise on January 9, 1870:

“In the Bonaparte family, there are some strange individuals whose wild ambitions cannot be satisfied and who, seeing themselves systematically relegated to the shadows, burn with spite at being nothing and having reached no power. They resemble those old girls who have never found a husband and who weep about the lovers they have not had either. Let us rank Prince Pierre-Napoleon Bonaparte in this category of lame unfortunates. He makes war on radical democracy but achieves more of a Waterloo than an Austerlitz.”

The attack was attributed to Ernest Lavigne, but the bylines weren’t always truthful in these papers, and Pierre recognized the real author as la Marseillaise founder Henri Rochefort. “I ask if your pen is backed up by your chest,” he wrote to Rochefort, along with his home address. “I promise that if you present yourself, you will not be told that I am out.” Rochefort caught his drift: “Let’s duel.”

On January 10, as Rochefort readied his seconds to issue a more official request, la Ravanche’s Paris correspondent, Paschal Grousset, dispatched two seconds of his own to invite Pierre to yet another duel. The fact that Grousset waited until Rochefort’s duel was in the works to do this (not to mention that his seconds were both la Marseillaise staffers) suggests collusion between Grousset and Rochefort, a suspicion still technically unproven. Whatever the case, everyone was itching for a fight, and when Grousset’s men showed up on Pierre’s doorstep—just to deliver the challenge, not to shoot—that’s exactly what they got.

The seconds in question were 36-year-old Ulric de Fonvielle and 21-year-old Victor Noir, more of a writer wannabe than the real thing. Noir, born Yvan Salmon, had adopted his mother’s maiden name as his pen name (already in use by his brother, Louis Noir), and been hired by la Marseillaise in December 1869 as a sort of copyboy-cum-bouncer.

“Burly, generally good-humored, given to a kind of mindless radicalism, he could also be aggressive,” Roger Lawrence Williams described him in his 1975 book Manners and Murders in the World of Louis-Napoleon. According to Williams, articles published under Noir’s byline were actually written by other staffers, and Noir spent most of his working hours guarding the door against disgruntled readers.

Accounts of the confrontation in Pierre’s salon differ. According to one version of the story, Pierre, assuming Grousset was in cahoots with Rochefort, yelled, “I am going to fight with Rochefort, not with one of his hacks!” Victor Noir retaliated by punching him in the face, so Pierre pulled a revolver from his pocket and shot Noir in the chest. The two seconds bolted, and Noir got as far as the front yard before crumpling to the ground. He died soon after being removed to a local pharmacy. (Meanwhile, Rochefort’s seconds had appeared at the house, and Pierre and his wife stood armed on the threshold in case of attack—but police de-escalated the situation before anybody could strike.)

Fonvielle would later claim that he and Noir confirmed that Grousset and Rochefort had indeed been conspiring, which provoked Pierre to hit Noir in the face first and then also shoot him. But a couple of crucial details support the former narrative: Noir’s face bore no damage, while Pierre’s cheek was visibly swollen. Someone in the pharmacy had even heard Fonvielle exclaim that although Pierre had killed his friend, “ç'est égal [it’s equal]; he got a hard slap!” Either way, the identity of Noir’s killer wasn’t in question—the courts would just have to decide if Pierre had acted in self-defense.

As Pierre awaited trial, Rochefort was planning what he hoped would be the best darn funeral this town had ever seen.

March of the Resistance

These days, Victor Noir is often characterized as a righteous journalist who stood up to the tyrannical Bonapartes and got slaughtered in cold blood for doing so. This is largely thanks to Rochefort and his allies, who saw in Noir’s death the chance to make him a martyr for the republic.

Rochefort presented him as “a child of the people” murdered by an empire that, being an empire, could never truly be liberal—nor separate itself from a bloody and authoritarian past. “I have been so weak as to believe that a Bonaparte could be other than a murderer!” Rochefort wrote in la Marseillaise. “I dared to suppose that a straightforward duel was possible in this family where murder and traps are tradition and custom.”

Leveraging the tragedy for political gain didn’t sit right with all republican sects, but even without the bloc’s full support, the funeral proved to be quite a spectacle. On January 12, somewhere between 80,000 and 200,000 people turned out to watch the hearse parade Noir’s body through Neuilly-sur-Seine, the Parisian suburb where his family planned to bury him. Amping up the sympathy factor was Noir’s teary-eyed fiancée, though Williams believed it “doubtful that Victor Noir had ever seen the woman.”

The endeavor had mixed results, politically speaking. Yes, Victor Noir was now a famous victim of the Bonaparte regime. But the funeral had been peaceful—stationed nearby were imperial troops whose presence may have helped discourage violence—and, per Williams, “it is likely … that a great share of the mob was merely curious, full of those who rallied for any lugubrious occasion.” In other words, while definitely a bad look for Napoleon III, the tragedy did not jolt the mob into toppling an empire.

The outcomes of the trials prompted by Noir’s death echoed this air of ambivalence. Later that month, Rochefort was found guilty of inciting insurrection via his coverage of Noir’s death in la Marseillaise and given six months in prison plus a 3000-franc fine. But when he learned the newspaper could continue operating, and he could even keep his seat in the French legislature, he laughed off his punishment with an “Oh, then I don’t give a damn.”

Pierre’s two trials, a criminal case for Noir’s death and a civil suit that his family filed for damages, took place in late March. The jury in the former, having bought that Pierre had acted in self-defense, cleared him of the murder charge, and in the civil suit, the court slashed his 100,000-franc fine to 25,000 (plus the legal fees incurred in the trial). Not only was the verdict a loss for Noir’s supporters, but their recalcitrance during the trials had harmed their credibility. Grousset and Fonvielle behaved so poorly on the witness stand—Grousset with blustering evasions and Fonvielle with general belligerence—that both were thrown out of court.

That said, it wasn’t exactly an out-and-out win for Pierre, a loose cannon and a failson who had just added a huge fiasco to his rap sheet. Napoleon III told his cousin that the “great scandal” had humiliated his kin, and when Pierre refused Napoleon’s request that he leave France, Napoleon insisted that he at least vacate Paris.

Perversely, the only real winner was Victor Noir: hailed a hero, mourned by the masses, and, thanks to one Jules Dalou, immortalized as a paragon of virility.

A New Grope

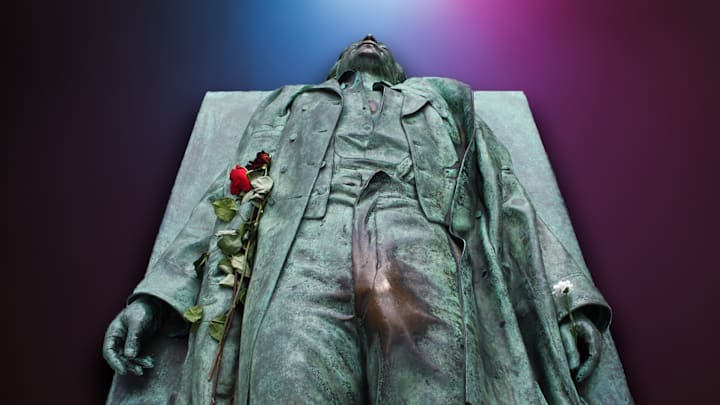

Noir’s death engendered enough sympathy that a national collection netted the cash needed to build him a bronze statue in Père-Lachaise. This didn’t happen immediately; in fact, he wasn’t relocated from the Neuilly cemetery until 21 years after his death. Sculptor Jules Dalou recreated him in stunning detail, lying on his back as though he’d just breathed his last.

Dalou was apparently so committed to photorealism that he gave Noir a noticeable bulge right where a noticeable bulge usually is. At some point, this feature spawned the legend that rubbing it would bestow a baby upon you—but it’s not totally clear how that legend came to be.

In 1962, a short piece that appeared in a number of American newspapers alluded to the custom of leaving a flower in Noir’s lapel: “Where except in Paris will you find a fresh boutonniere placed daily in the lapel of a life-size statue of a romantic figure of a century ago? Anonymous Parisian connoisseurs of joie de vivre have kept bright the spirit of dashing Victor Noir in this unique way ever since the French gallant passed from the gay boulevard scene 100 years ago.”

It seems believable that Noir’s bulge helped inspire this portrayal of him, which is almost farcically at odds with the history that earned him a spot in the cemetery and with the effigy itself—again, modeled to look like a homicide victim.

During the 1970s, his persona became ever more exaggerated. In September 1970, London’s Sunday People called Noir “a handsome young journalist” with “an unrivaled reputation as a Don Juan.” His statue, the paper wrote, was “carved with regard for his amorous reputation, [showing] him in a state of some undress and leaving nothing whatever to the imagination of love-hungry Parisiennes.” It also claimed that most of Noir’s 100,000 funeral guests were “weeping women.”

Though that article said nothing of any superstition associated with the tomb, it attested to the steady stream of visitors whose “attentions and kisses” had worn the verdigris patina off Noir’s crotch. A 1971 report did reference the legend “that rubbing [his body] cures sterility,” and another in 1974 (which labeled him a “philanderer”) mentioned that “climbing on his tomb is reputed to help cure frigidity.”

All this to say that Noir’s final resting place was a certified hotspot by the early 1970s, and his polished bronze body parts—lips, groin, and even feet—had the sheen to prove it. While the specifics of the legend itself vary widely, a spouse, a baby, and some great sex are all things you stand to gain by engaging with the effigy in some way, be it a kiss, a caress, or a flower left in Noir’s hat.

This business more or less continued as usual until 2004, when officials tried to stop what they called “indecent fondling” by erecting metal barriers around the statue. But French television host Péri Cochin led a small contingent of women in protest, and Paris deputy mayor Yves Contassot quickly restored access. Still, he asked them to treat the relic gently.

“You can touch, but not rub. You rub and you will be punished,” he said. “We need to take care of it without falling into excessive, American-style prudery. I respect those who think it makes women fertile, but cemeteries also require respect for decorum.”

For visitors looking to better their love lives—or help combat excessive, American-style prudery—without waiting in line for Victor Noir, Père-Lachaise plays host to another Jules Dalou sculpture: Auguste Blanqui, an esteemed socialist rabble-rouser in attendance at Noir’s funeral, whose bronze death shroud also bears a noticeable bulge.

Discover More Stories About Cemeteries: