It started with Prince.

In 1985, Mary Elizabeth “Tipper” Gore decided to sit down and listen to an album she had just purchased for her 11-year-old daughter, Karenna. Purple Rain was being hailed as a masterpiece, and although Prince was perceived as somewhat of a salacious performer, nothing on the album’s sleeve indicated it would be inappropriate for children.

Gore was therefore startled when she and her daughter heard “Darling Nikki,” a song in which Prince sings about masturbation. She was shocked music with sexual overtures was available without any kind of advisory or warning labels. She was angered further when she tried to return Purple Rain to the store and was told that they could not offer her a refund because it had been opened.

While most parents would simply discard the album, Gore—the wife of then-Senator and future vice president Al Gore—had the power to take it a step further. By the end of the year, Tipper Gore would be testifying during a Senate hearing that also demanded answers from the likes of Dee Snider, Frank Zappa, and John Denver. (Yes, that John Denver.) When the smoke cleared, both the music industry and the political arena would be rocked.

We’re Not Gonna Take It

Rock is just one of many musical genres that has never been short of critics. In the 1920s, jazz and blues were labeled “the devil’s music,” with moral authorities painting them as corrupting influences. In the 1950s, Elvis Presley and his gyrating pelvis were of great concern, with community leaders fearing his moves were too sexually charged for young audiences to handle. In the 1970s and 1980s, heavy metal was at the forefront of the satanic panic hysteria, complete with purported subliminal messaging.

While sexual subtext has always been present in music, Gore felt the ‘80s were a tipping point. Along with fellow “Washington wives” Susan Baker (the wife of Ronald Reagan’s treasury secretary James Baker), Sally Nevius (the wife of ex-Washington city council chairman John Nevius), and Pam Howar (the wife of local realtor Raymond Howar), Gore formed the Parents Music Resource Council, or PMRC, with the mission of providing parents with disclosures about the content of albums. Gore likened the project to the Motion Picture Association of America, or MPAA, which had a ratings board for movies. Gore argued that the Record Industry Association of America (RIAA) should have something similar, suggesting an X for profane or sexually graphic lyrics, O for satanic (or occult) content, D/A for drugs and alcohol, and V for violence.

“How does the average working parent know which artist represents what?” Gore asked in a 1988 interview with The Washington Post. “You’re talking about a complex marketplace out there. Kids come in and say they want to go to a Slayer concert. How do parents know who this group is versus a Whitney Houston or U2?”

Few people—then or now—would confuse Slayer with Whitney Houston, but Gore persevered. To draw attention to the goal, the PMRC circulated what was known as the “Filthy 15,” a scandal sheet that shamed what the group felt were the most offensive songs in circulation. “Eat Me Alive” by Judas Priest, “Sugar Walls” by Sheena Easton, and “We’re Not Gonna Take It” by Twisted Sister were all deemed objectionable and deserving of X, O, V, and/or D/A labeling.

“Treating Dandruff by Decapitation“

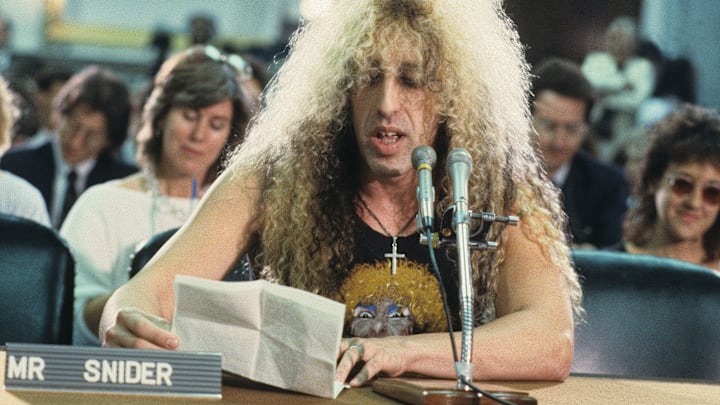

The ensuing public dialogue over whether music should be labeled resulted in a Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee hearing held in September 1985. Gore was asked to speak, as were musicians like Zappa and Snider, neither of whom were enthusiastic about the PMRC’s objectives.

Likening such regulation to “treating dandruff by decapitation,” Zappa insisted such steps infringed on civil liberties, including for those buying the albums, and amounted to an attack on the First Amendment. He would later label Gore a “cultural terrorist.”

Snider agreed, saying that any review board evaluating music stood a high chance of misinterpreting lyrics, as the PMRC had already done with “We’re Not Gonna Take It.” The violence in that song, he said, was meant to be satirical.

“On this list is our song ‘We’re Not Gonna Take It,’ upon which has been bestowed a ‘V’ rating, indicating violent lyrical content,” Snider said. “You will note from the lyrics before you that there is absolutely no violence of any type either sung about or implied anywhere in the song. Now, it strikes me that the PMRC may have confused our video presentation for this song ... with the lyrics, with the meaning of the lyrics. It is no secret that the videos often depict storylines completely unrelated to the lyrics of the song they accompany.”

Zappa and Snider had a curious bedfellow in John Denver, whose wholesome image seemed far distanced from the performers found on the “Filthy 15” (Denver wasn’t even included on that list). Snider anticipated Denver might fall on the side of the activist group, considering his clean image. But even Denver was critical of the PMRC, recalling that his hit “Rocky Mountain High” had encountered resistance from some radio stations, owing to its nonexistent hints at drug use. The PMRC, Denver added, reminded him more of a Nazi book-burning regime.

As expected, some politicians used the hearing as a pulpit to flirt with censorship. “It is outrageous filth and we must do something about it,” South Carolina senator Ernest F. Hollings said. “If I could find some way constitutionally to get rid of it, I would.” Other senators held up rock posters or played music videos they considered offensive. It was very likely the first and only time hard rock was emitted from loudspeakers on the Senate floor.

Under threat of possible government legislation, the RIAA agreed to institute a parental notification system. (In fact, they had gotten 19 labels to agree on some form of warning even before the hearing, though the alerts weren’t as visible as the PMRC would have liked.) In a form of self-policing, the recording labels themselves would deem which lyrics were potentially offensive. It would not be as elaborate as the ratings system recommended by the PMRC, and so-called occult mentions wouldn’t be labeled. There would instead be a single sticker affixed to albums with sex, drug, or violent content: Parental Advisory: Explicit Lyrics.

On the Record

Gore remained adamant she was never out to ban any type of music, only to alert parents to music they might deem inappropriate for children. But the advisory label (or, as some folks called it, a “Tipper sticker”) had consequences that went far beyond that.

Some stores, like Walmart, refused to carry albums with the warning; certain venues prohibited artists with the scarlet (actually, black) label from performing. And then there was the reverse-psychology effect. In broadcasting that certain albums were controversial, it made people—especially teenagers—want them even more.

In 1988, Gore broadened the scope of her watchdog efforts by singling out MTV for suggestive music videos. The PMRC helped convene a symposium in which the potentially harmful effects of kids watching such content were discussed. (Among them: drug abuse, suicide, and satanism.)

There were consequences for Gore, too. There was speculation Al Gore’s 1988 Democratic presidential run was hampered by Tipper’s visibility and crusade, which may have roiled entertainment factions that normally leaned liberal.

Gore ultimately became vice president when Bill Clinton—who actively courted the youth vote by appearing on MTV and playing the saxophone on The Arsenio Hall Show—was elected in 1992. When Gore ran for president in 2000, he received an unlikely endorsement from Dee Snider, owing to their similar views on the environment and abortion rights.

Tipper Gore remained adamant that her crusade was not an attempt at censorship, just informed choice. “One woman called me at Christmas and said, ‘I want to thank you. I was buying four tapes for my 10-year-old son. I turned them over and two of them had labels on them ... I exchanged them,’” she said in 1988. Gore ultimately left the PMRC in 1993, shortly after Al Gore became vice president.

The controversy repeated itself that same year, when the video game industry came under fire for its depictions of violence. Senator Joe Lieberman was at the forefront of congressional hearings in which game manufacturers like Nintendo and Sega were called to explain the spine-ripping violence of games like Mortal Kombat. As with the RIAA, the industry opted to implement a ratings system rather than fall under direct government supervision.

Though the RIAA still advocates for use of the Parental Advisory label, it seems to have less influence in the age of streaming digital music. There remains no clear consensus on whether such warnings keep adult-oriented material away from kids, or what the possible psychological consequences might be if they don’t. More often than not, adolescent rebellion tends to resist such barriers.

Or, as Judas Priest put it in a timely 1986 song titled “Parental Guidance”: “Don’t you remember what it’s like to lose control? ... We don’t need no parental guidance.”