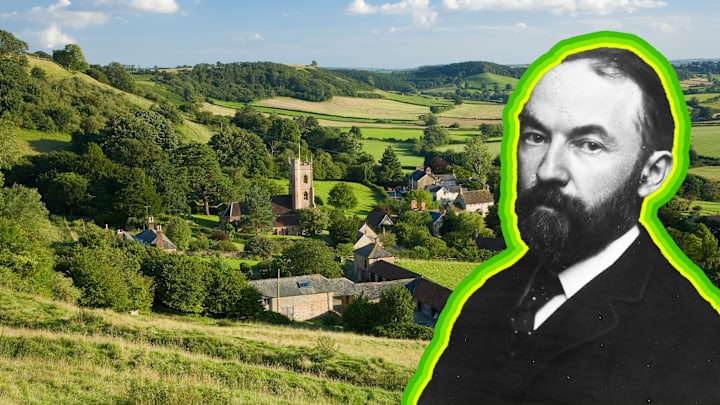

Born in 1840 in the English county of Dorset, author and poet Thomas Hardy is best known for his novels of rural realism, including Far from the Madding Crowd (1874), Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891), and the controversial Jude the Obscure (1895). Hardy’s characters, living in the fictional region of Wessex, struggle against the mores of industrialized, Victorian England. Here are 11 facts about their reticent creator.

1. Thomas Hardy didn’t attend formal school until he was 8.

Hardy was the oldest of four siblings. His father, also named Thomas Hardy, was a stonemason, and his mother, Jemima, was a well-educated woman who taught her son at home. Hardy spent most of his childhood in the picturesque countryside that inspired his imaginary Wessex.

2. He trained to be an architect.

As a teenager, Hardy apprenticed under local architect James Hicks, for whom he and his father had restored Woodsford Castle. Later, in his early twenties, Hardy worked for architect Arthur Blomfield in London before ill health forced him back to his hometown in Dorset and another job with Hicks. He also worked for architect G.R. Crickmay in the seaside community of Weymouth.

Though he would eventually turn his attention to writing, Hardy never left architecture completely behind. A book published in 2018, The Wessex Project: Thomas Hardy, Architect, explores Hardy’s work in the context of his literature.

3. Hardy exhumed a London cemetery.

In the mid-1860s, while Hardy worked for Blomfield, the Midland Grand Railway underwent a large expansion and hired Blomfield’s firm to relocate a cemetery at St. Pancras in London.

The job fell to Hardy—who, after exhuming and reburying the remains, took the hundreds of headstones and arranged them in a circular pattern around an ash tree. The spot is now known as “the Hardy Tree,” and even boasts its own Google reviews.

4. The term cliffhanger likely emerged from one of Hardy’s novels.

Charles Dickens is credited with popularizing the “cliffhanger,” a plot device in which a scene or story is paused at a dramatic moment. But scholars have said the term originated in Hardy’s 1873 novel, A Pair of Blue Eyes, which was first published in serial form in Tinsley’s Magazine. In the book, a character named Henry Knight is literally hanging from a cliff.

5. Hardy used his architectural skills to design his own house.

Hardy designed the Victorian house that he would live in from 1885 until his death in 1928, calling it Max Gate after a local toll-gate named for its keeper, Henry Mack (“Mack’s Gate”). Hardy’s brother built the house over two years.

Hardy kept adding on to the house during his 43 years there and planted nearly 2000 trees on the grounds. He hosted a number of luminaries, including Robert Louis Stevenson, Rudyard Kipling, W.B. Yeats, H.G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, and the Prince of Wales, who would later be crowned King Edward VIII.

Today, the house is owned by the UK’s National Trust and is open for tours. In addition to a vegetable garden, flower beds, and a croquet lawn, the property includes a pet cemetery that Hardy and his first wife, Emma, created for their cats and dogs. Their favorite pet, a dog named Wessex that was known to bite visitors, is buried there.

6. Some retailers sold Jude the Obscure in brown paper bags.

Hardy’s novel Jude the Obscure, which discussed sex and criticized marriage, class, the church, and education, was considered too racy and controversial for Victorian sensibilities. It first appeared as a serial publication in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine from 1894 to 1895, for which Hardy was forced to make edits on some of the candid passages. He reinstated his prose when publishing the novel in 1896.

Critics panned it; the Bishop of Wakefield reportedly burned his copy. Discouraged, Hardy gave up writing novels, making Jude the Obscure his last work of fiction. He personally donated the original manuscript to the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1911.

7. Thomas and Emma Hardy supported women’s rights.

Hardy married Emma Gifford in 1874. Though the pair had a strained relationship, she encouraged him in his literary career and they both supported women’s rights, albeit by different approaches.

Emma participated in marches and demonstrations and wrote articles on women’s civil rights. She was a member of the London Society for Women’s Suffrage until 1909, when she felt it had become too militant.

Thomas regarded women’s rights from the perspective of how much more effective politics might be if women had more pull. He even went so far as to suggest that the British monarchy worked better under female monarchs. As for the women’s vote, he felt it would disrupt societal conventions—religion, marriage, gender roles, and more. Hardy was in favor of this shakeup, but the leaders of the suffrage movement thought his views would not help their cause (Hardy concurred) and so they didn’t advertise his thoughts on the matter.

8. Hardy was appointed to the Order of Merit.

In July 1910, King Edward VII appointed Hardy to the Order of Merit, an honor given to those who had provided “exceptionally meritorious service in our Crown services or towards the advancement of arts, learning, literature, and science.” The order is limited to 24 living members at a time, and members can add “O.M.” after their name.

9. Hardy received multiple nominations for the Nobel Prize in Literature—and never won.

From 1910 to 1927, Hardy received 25 nominations for the prize, including nine nominations in 1922 alone. Although Hardy’s work was well regarded, some felt he was shut out because his oeuvre didn’t fit the Nobel’s requirement that it be of an “idealistic tendency.”

10. Hardy wrote a poem to raise money for Titanic survivors and victims’ families.

After the Titanic sank on April 15, 1912, Hardy wrote a poem for a fund set up for survivors and families of victims. “The Convergence of the Twain: Lines on the Loss of the Titanic” describes the fateful meeting of the ship and the iceberg, and was published in The Fortnightly Review in June that year. The poem was republished on the 100th anniversary of the ship’s sinking.

11. He destroyed his first wife’s diaries.

Hardy is often described as shy or reticent, and, like many writers, he wanted control of his stories, whether fictional or real. After Emma’s death in 1912, he burned a manuscript she wrote, titled “What I Think of My Husband,” along with most of her diaries. Emma had reportedly destroyed letters between herself and Hardy as well.

Hardy then married Florence Dugdale, who was 38 years younger than he, in 1914. Following the author’s death from pleurisy on January 11, 1928, Florence did away with more of Hardy’s correspondence and personal papers.

12. Hardy’s heart is buried separate from his ashes.

Hardy wanted to be buried at Stinsford in Dorset, a place he revered, near his first wife and his family. But his executors had other plans. They pressured Florence to agree to have Hardy interred at Westminster Abbey’s famous poets’ corner. To solve the problem, Hardy’s heart was buried in Stinsford, while the rest of his cremated remains were laid in the abbey near the grave of Charles Dickens.