In May 1927, a reader of the Spokesman-Review in Spokane, Washington, wrote in to a physician’s column with a pressing pregnancy-related issue.

“I have heard for some time that if an expectant mother, say during her fourth month, should want anything, she must have it or otherwise it will in some way affect the child. For instance, if she should take a notion that she wants strawberries, and does not get them, will the child be marked with red marks resembling strawberries?”

While the columnist in question, Dr. W.A. Evans, responded with common sense (“Wrong there, from every angle”), it was not uncommon at the time for birthmarks to provoke a number of superstitions.

What are birthmarks?

It’s estimated that roughly 10 percent of all babies are born with some type of birthmark, which can be raised or flat, red or brown, large or small. Vascular birthmarks are the result of overgrown blood vessels, while others are simply cells that have different pigmentation from the rest of the skin. (Moles are one type of pigmented birthmark.)

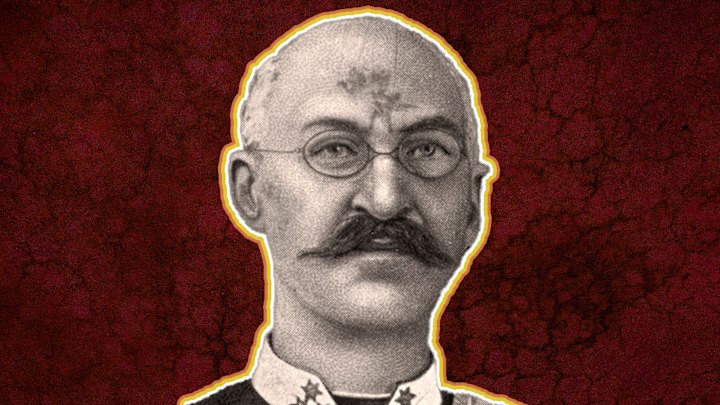

Some can be rather large. There is probably no more famous a birthmark than the one sported by onetime Soviet Union leader Mikhail Gorbachev. As Cold War tensions flared in the 1980s, Gorbachev’s large, map-shaped blemish on his sparsely-haired forehead was immediately recognizable. Such marks are often referred to as port wine stains, for their resemblance to a spilled drink.

Most, like Gorbachev’s, are benign; occasionally, some require dermatological intervention. Beyond that, science isn’t really sure what causes them, which has allowed a lot of myths and superstitions to take hold.

Strange Old Theories About the Origins of Birthmarks

Perhaps the most punishing of birthmark misconceptions was the notion that they could be “evidence” a community had a witch in their midst. During the infamous Salem witch trials of the 17th century, witchery was suspected if a woman had a birthmark, mole, or other skin lesion. Rather than be considered an anomaly of pigment or vessels, these were dubbed “witch’s marks” or “devil’s marks” and were added to the pile of bunk science that led to convictions of witchcraft.

Birthmarks have also long been intertwined with the idea of maternal impressions, or thoughts and activities undertaken by a pregnant person that have the potential to influence their unborn child. Food cravings were once a popular explanation. As the theory went, if the pregnant parent had a food craving and ignored it, their infant would pop out with a birthmark in the shape of the food they passed up. Or, the pregnant person might scratch themself somewhere on their skin, which would result in the birthmark appearing in the same spot on the baby’s body.

Maternal impressions could go both ways. If a pregnant person admired a Greek statue, then perhaps they’d have attractive offspring. Or it could be calamitous: Some dreaded running into a rabbit or hare, lest the baby be born with a cleft (or hare-) lip. Another tale had it that a person running into a one-legged man might have a one-legged baby. The belief was that experiencing any kind of fright at all could leave a permanent mark.

While those beliefs endured into the 20th century, as evidenced by the concerned Spokesman-Review reader, rational explanations circulated well before then. One correspondent to a medical journal in 1898 complained of the “pestiferous hobgoblin” that was the prenatal impression.

While people have largely dismissed such myths, folklore can still inform how people interpret birthmarks. For centuries, the stork has been emblematic of fertility, delivering babies to happy families by gently biting them with their beaks. (They also allowed parents to avoid discussing conception.) If a child had a birthmark on the back of their neck, it was known as a stork bite, which is a good deal more pleasant-sounding than having the mark of the devil.