The stories behind paintings and sculptures can be as interesting as the work itself; in fact, looking “behind the easel” can even shed light on our shared history and culture. From Mark Rothko's Seagram murals to Gustav Klimt's Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, here are stories behind artistic masterpieces you should know, adapted from an episode of The List Show on YouTube.

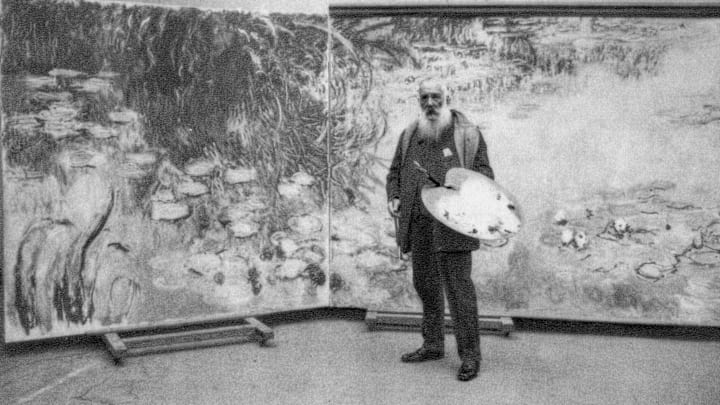

1. Claude Monet's Water Lilies Series

Claude Monet’s beautiful gardens in Giverny once caused him to curse out an entire town. The impressionist would go on to paint his famous water lily paintings in the serene setting, but navigating the small French commune’s bureaucracy proved stressful. Locals objected to Monet’s plans for an Asian-influenced water garden, fearing the environmental impact of introducing non-native plant species to the area. They made it so difficult to acquire the land that Monet once wrote to his wife, “I want no longer to have anything to do with … all those people in Giverny … S*** on the natives of Giverny.”

Despite his initial frustrations, Monet succeeded in acquiring the land necessary for his gardens, and soon built the Japanese footbridges he would make so iconic. An avid gardener, Monet also acquired a number of newly-bred, multicolored species of water lilies, though in his words, he “grew them without thinking of painting them.” Luckily, the influential painter was able to make that creative leap on his own, but we still might not have gotten some of his most beautiful later pieces without an assist from Georges Clemenceau, the former Prime Minister of France who also happened to be an old friend of Monet’s.

When the artist developed cataracts late in life, he was resolved to avoid eye surgery, even saying he would “give up painting if necessary.” Clemenceau—who would later tell his friend that “complaining gives you the greatest joy in life”—helped convince his gifted friend to get the surgery. Monet eventually completed the massive water lily paintings that he called his Grandes Decorations and donated the pieces to the French state, as he had promised. Today they are housed in Paris’s Musée de l’Orangerie.

2. Édouard Manet's Bonus Asparagus

Monet’s rough contemporary, Édouard Manet, once gifted what may be history’s most valuable stalk of asparagus. When the French art critic and collector Charles Ephrussi purchased a still-life painting of a bunch of asparagus, Manet charged him 800 francs. Ephrussi sent 1000 francs in payment. As either a token of appreciation for the extra cash or evidence that he couldn’t avoid an opportunity for a good dad joke, Manet created an additional painting of a single stalk of asparagus and sent it to his patron with a note reading, “there was one missing from your bunch.” Today, the bonus picture hangs in Paris’s Musee D’Orsay.

3. Mark Rothko's Seagram Murals

On February 25, 1970, Mark Rothko’s nine Seagram murals arrived at the Tate Gallery in London, the very same day Rothko was found dead in New York. But that sad bit of historical timing is just the final chapter of an interesting story.

The paintings had originally been commissioned by Philip Johnson for the newly built Seagram building, the most expensive skyscraper of its type when it was built, and were meant to be hung in the building’s Four Seasons restaurant.

A venue like The Four Seasons, in the center of corporate America, didn’t seem like a natural fit for a high-minded artist like Rothko. He had his reasons, though. As he told Harper’s Magazine editor John Fischer, “I accepted this assignment as a challenge, with strictly malicious intentions. I hope to paint something that will ruin the appetite of every son of a bitch who ever eats in that room.”

Rothko also accepted the assignment with an “out” built into his contract. At any point, he could return the money and retrieve his paintings. After eating a meal at the Four Seasons, Rothko is said to have remarked: “Anybody who will eat that kind of food for those kind of prices will never look at a painting of mine.” That one meal may not be the sole reason for his about-face, but he withdrew from the agreement and donated the pieces to London’s Tate Gallery. They eventually ended up in the Tate Modern. Playwright John Logan actually dramatized the creation of the Seagram murals in his Tony-winning play, Red.

4. Gustav Klimt’s Woman in Gold

Gustav Klimt’s Woman in Gold depicts Adele Bloch-Bauer, the wife of sugar mogul Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer. When the Nazis invaded Austria in the late '30s, they stole from wealthy Jews like Bloch-Bauer, taking his entire art collection and his prized Stradivarius cello. Years later, with the painting then hanging in Vienna’s Austrian Gallery at Belvedere Palace, Frederick’s niece, Maria Altmann, went on a mission to reclaim her family’s property. A lengthy legal battle ensued. Discussing the Austrian government’s tactics with The Los Angeles Times back in 2001, Altmann said “They will delay, delay, delay hoping I will die. But I will do them the pleasure of staying alive.”

The United States Supreme Court even weighed in at one point and the painting was eventually returned to Ms. Altmann, who then sold the piece to philanthropist Ronald Lauder so he could put it on display at Manhattan’s Neue Galerie.

5. The Benin Bronzes

Of course, the Nazis aren’t the only ones to have stolen precious works of art. One particularly damning episode took place near the end of the 19th century, during the colonial fervor that’s been called “The Scramble for Africa.” In 1896, the British Acting Consul in the Niger Coast Protectorate, Captain James Robert Phillips, sought permission to depose the Oba, or ruler, of Benin, a kingdom located in present-day Nigeria. Philips believed the Oba was standing in the way of profitable trade in the region and wrote, “I have reason to hope that sufficient ivory would be found in the King's house to pay the expenses incurred in removing the King from his stool."

When Philips and his men were denied an audience with the Oba they went anyway, ostensibly on a peaceful mission (though that account has been called into question). Almost the entire party was killed, and in less than two months, retaliatory British forces were sent to occupy Benin City. While the number of casualties is unknown, contemporary accounts make it clear the number was substantial. British forces burned down buildings, including the Royal Palace, and looted thousands of works of art, including the so-called Benin Bronzes.

These sculptures—many of which are actually made of brass—represent not just part of Benin’s history, but artistic excellence so advanced that an early 20th century curator of the Berlin Ethnographic Museum declared them to “stand even at the summit of what can be technically achieved.” Many of the sculptures were made with a time-intensive “lost-wax casting process” by master artisans in Benin’s brass-casting guild.

Today, most of the Benin Bronzes are in museums and private collections far outside the original Kingdom of Benin. The British Museum owns over 900 such pieces. And while new conversations about repatriating ill-gotten artwork have led to initiatives like the Benin Dialogue Group and plans for a new museum in Benin filled with artwork loaned back to the area, very little has been permanently returned to Nigeria, or to the present-day Oba. One notable exception comes from a Welsh doctor named Mark Walker, whose grandfather took part in the 1897 raid of Benin. Through a series of coincidences and the efforts of two former British police officers, Steve Dunstone and Timothy Awoyemi, the younger Mr. Walker helped return two artifacts to the Oba of Benin back in 2014. In 2021, it was announced that German museums would work to repatriate some of their Benin Bronzes as early as 2022.

6. Kara Walker's A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby

Kara Walker’s work is also inextricably tied to the legacy of colonialism and slavery. While she became famous largely for her provocative work with paper cutouts, it was a much different type of piece that showed some of the possibilities and limitations of public art. In 2014, she installed A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant in the former location of that same Domino Sugar Refining Plant in Brooklyn, New York.

The piece was financed largely by the real-estate company Two Trees, which owned the Domino Sugar Refinery site and was planning a costly development at the location. That a giant real-estate outfit would underwrite work from an iconoclastic artist like Walker would prove to be just one of the project’s many ironies.

The exhibit’s centerpiece was a massive sculpture that took a team of dozens to create. It mixes the posture of a sphinx with elements taken from stereotypical depictions of the “mammy” archetype. With the entire figure covered in thousands of pounds of actual sugar, donated by Domino, and the floor of the site still stained with molasses from its history as a working plant, the piece alludes to the history of sugar production and trade, and the bitter role the ingredient played in accelerating the African slave trade. Walker called her piece A Subtlety, a nod to the old label for grand sugar sculptures created for nobility of the past, though her towering work is, as she recognized, unsubtle in many ways.

Though the sculpture’s representation of breasts and genitalia could be read as allusions to the hyper-sexualization of Black women in American culture, or to an awful legacy of sexual violence, many of the exhibition’s attendees seemed blissfully unaware of that history. Some posed suggestively with the sphinx; others made adolescent bodily jokes on Instagram and other social media platforms. Walker, for her part, anticipated the reaction, saying, “I put a giant 10-foot vagina in the world and people respond to giant 10-foot vaginas in the way they do.” She did choose to surreptitiously film some of these reactions, and compiled them into its own piece, a video titled An Audience.

7. Georgia O'Keeffe's Gerald's Tree

Georgia O’Keeffe spent many years visiting and then living near the Ghost Ranch in New Mexico—an area she might never have discovered if she wasn’t such a terrible driver.

Her difficulties in learning to operate a car were “legendary,” according to the art critic Calvin Tomkins. As she told Tomkins back in 1974: “One day, the boy who was trying to teach me to drive said he knew of a place he thought I’d like better than any I’d seen, and he brought me [to the Ghost Ranch]. … I think the story is that a family was murdered there, and that from time to time a woman carrying a child appears in the original house—that’s the ghost. Well, I came back a few days later, alone, and asked if I could stay.” She would go on to paint many of her master works in or near the stark setting.

O’Keeffe didn’t leave everything up to chance, though. She eventually started driving her Model-A Ford to find interesting landscapes, and then used it as a mobile studio, where she painted pieces like Gerald’s Tree. Upon arriving at a location, O’Keeffe would remove the detachable driver’s seat and unbolt the passenger seat, turning it around so she could face the back-seat “easel.” The mobile studio allowed O’Keeffe to paint during oppressively hot days and protected her from the bees that tended to gather as days wore on.

8. John Everett Millais's Ophelia

O’Keeffe wasn’t the only artist who had to contend with bugs to bring us beauty. While John Everett Millais was painting his Ophelia, he wrote of the stresses of painting in the open air, saying, “My martyrdom is more trying than any I have hitherto experienced. The flies of Surrey are more muscular, and have a still greater propensity for probing human flesh.” On top of that, Millais was threatened with reproach for trespassing on a field and destroying the hay.

His model, Elizabeth Siddal, had it even worse. In order to represent the story of Ophelia’s drowning from Hamlet, Millais had Siddal pose in a bathtub full of water. The website My Modern Met describes the unforeseen consequences like this: “During one sitting, the oil lamps responsible for keeping the water warm went out, and Siddal grew severely ill as a result.” Her father eventually had to pressure the artist into paying for his daughter’s medical bills.

Millais may have felt that the tumultuous process “would be a greater punishment to a murderer than hanging,” in his own melodramatic words, but the finished painting stands today as one of the finest exponents of the pre-Raphaelite movement.

9. Frida Kahlo's Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky

Many of Frida Kahlo’s paintings employ visual metaphor to allude to her tumultuous life, but her Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky doesn’t leave much guesswork for the modern viewer. In the painting, Kahlo holds a note of dedication to the Russian revolutionary reading “con todo cariño.” That Spanish phrase, which can be translated as “with all love,” probably doesn’t imply the same level of romantic passion as “con todo amor” would have, but if she had made the piece half a year earlier there’s no telling what she might have inscribed.

Kahlo and her husband, Diego Rivera, were avowed Marxists. It was actually Rivera who convinced Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas to offer Trotsky political asylum in Mexico years after he was exiled from the Soviet Union. Trotsky and his wife stayed in their hosts’ second home, the Casa Azul, while in Mexico. That’s when things get messy. Or, given the turbulent marriage between the two famed Mexican painters, messier.

Perhaps, in part, to get revenge for Rivera’s affair with her sister, Cristina, Frida began her own affair with Trotsky. The lovers apparently conspired right in front of Trotsky’s wife, who couldn’t follow along in English, their shared second language. Some of their meetings actually happened in Cristina’s house.

By July of 1937, the relationship had fizzled out, with Frida reportedly telling a friend, “I am very tired of the old man.” The self-portrait was, nonetheless, dedicated to Trotsky in November. A few years later he was killed in Mexico by an undercover agent working for Stalin, and Kahlo was actually brought in for questioning by the Mexican police.

10. Hilma af Klint's Paintings for the Temple

When the Swedish painter Hilma af Klint rose to prominence decades after her death, the art historian Julia Voss suggested that “[a]rt history has to be rewritten.” For years, many had considered artists like Wassily Kandinsky and Francis Picabia the fathers of abstract art. Before they began experimenting with abstraction around 1910, the medium was dominated by figurative work representing real or imagined scenes. Af Klint’s abstract, often geometric pieces, though, predate the work of the supposed abstract pioneers by several years. And the story of why it took so long to rediscover her work is almost as interesting as the motivations behind the pieces themselves.

Af Klint did show her more traditional, figurative paintings during her life, and even exhibited her more abstract work in London back in 1928. Perhaps the tepid reaction to the work led her to believe she was ahead of her time. A skeptical studio visit from the philosopher Rudolf Steiner, whose Anthroposophical Society af Klint was an acolyte of, certainly didn’t help. Whatever the reason, af Klint decided to bequeath her paintings to her nephew, with the clear direction that he not display any of them until 20 years after her death.

Af Klint had taken an interesting journey to arrive at abstraction. She attended her first séance at 17, and eventually formed a spiritual collective of five women who called themselves De Fem (or “the five”). The women went on to conduct other séances, with one resulting in a “commission” for a series of paintings from a spiritual entity the group called High Master Amaliel. Af Klint eventually fulfilled this commission by creating 193 “Paintings for the Temple.” And while af Klint once said “the pictures were painted directly through me,” suggesting some kind of channeling, she also specified that “It was not the case that I was to blindly obey the High Lords of the Mysteries,” leaving some tension between her own agency and the spiritual dimensions of the work.

The temple af Klint had envisioned for her opus was a custom-built spiral that never came to be. It’s fitting, then, that a record-breaking 2018 exhibition of her work took place at a museum once envisioned as a “temple for the spirit” by its director, Hilla von Rebay: Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic spiraled masterpiece, the Guggenheim.

11. Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine's Sunday in the Park With George

Today, Stephen Sondheim is widely regarded as Broadway royalty, but in 1982 he was coming off one of the biggest flops of his career, Merrily We Roll Along, which had run for just 16 performances.

Searching for inspiration, he and collaborator James Lapine turned to visual art, including Georges Seurat’s pointillist painting, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. Lapine noted that, though the painting resembled a scene that might be seen on a stage, the main character—Seurat himself—was absent.

The musical that eventually came out of this moment, Sunday in the Park With George, beautifully examines the creative process, with a focus on A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, but it wasn’t a biography of the painter, really. Seurat died at just 31 years old, and one biographer described him as inclined to secrecy and isolation. We know that the painting took over two years to complete, and that Seurat had a secret mistress, whom Sondheim obliquely worked into his musical, but the fictionalized Georges was almost entirely Sondheim’s invention, whether by dramatic necessity or want of available information.

It couldn’t have been a simple matter to dramatize the internal inspiration and rigorous dedication needed to create a piece as singular as La Grande Jatte, but, as someone once said, art isn’t easy.