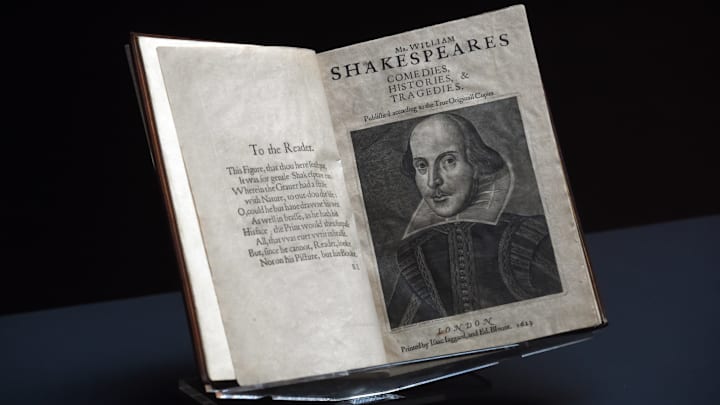

This year marks the 400th anniversary of the printing of William Shakespeare’s First Folio, a key moment in literary history. Officially titled Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies, the more than 900-page tome collected together 36 of the Renaissance writer’s plays for the first time. The impact of the 1623 book is still felt across the arts and the English language to this day: There are over 1000 adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays—making him the most filmed author in history—and his works contain the first recorded usage of many words. Here are 11 facts about the Bard’s momentous First Folio.

1. Shakespeare had no involvement in the printing of the First Folio because he had died seven years prior, in 1616.

Two of Shakespeare’s friends, John Heminge and Henry Condell—who were also actors in the King’s Men, the playing company for which the Bard wrote—put together the First Folio as a tribute to their departed friend. They created the book by referring to Shakespeare’s drafts, individually printed editions of his plays, and prompt books (the script of a play along with staging details, such as blocking and sound cues). The tome was largely financed by bookseller Edward Blount and it was printed by Isaac Jaggard, who managed the print shop owned by his father, William).

2. Folio describes the book’s physical format.

A folio was a type of book made by folding paper only once, creating four pages per sheet. Folios were expensive due to their large size and high quality bindings, so typically, only important texts—usually of a historical, royal, or religious nature—were published in this format. Plays were typically printed individually in cheaper quarto editions, a small booklet made up of sheets that had been folded twice to yield eight pages. Shakespeare wasn’t the first playwright to receive the special treatment of a folio edition, though: Ben Jonson published a folio of his own plays in 1616.

3. Roughly 750 copies of the First Folio were printed—and 235 have survived to this day.

On November 8, 1623, the First Folio was entered into The Stationer’s Register—which recorded publishing rights—and went on sale. Bound copies were sold for £1 (around $240 in today’s money) and unbound copies sold for 15 shillings (around $150). Each copy is distinctive, not only because of owners handling and annotating their books, but also because spelling mistakes were made and corrected throughout the printing process.

Many of the 235 copies that are known to exist today are missing pages—only 56 copies contain all 908 pages. The Folger Shakespeare Library, in Washington, D.C., has the largest collection of First Folios in the world, clocking in at 82 copies. Every so often a copy is rediscovered and added to the list (although nine copies have also somehow gone missing since being catalogued). The most recent one was found in 2016 at Mount Stuart House on the Scottish Isle of Bute.

4. In 2020, a copy sold for nearly $10 million, making it one of the most expensive works of literature ever sold.

Buying a First Folio back when it was first published was a luxury, but these days only millionaires can even consider purchasing one (and even then only when they become available, which is rarely). In 2020, Oakland, California’s Mills College auctioned off their copy of the First Folio. It sold for $9,978,000 to rare book collector Stephan Loewentheil, making it one of the most expensive books ever sold.

5. Without the First Folio, 18 of Shakespeare’s plays would have been lost to time.

While many of Shakespeare’s plays had previously been printed in quarto editions, 18 hadn’t been published at all and would likely have been lost if the First Folio had not been published. In alphabetical order, the plays that were saved are All’s Well That Ends Well, Antony and Cleopatra, As You Like It, The Comedy of Errors, Coriolanus, Cymbeline, Henry VI Part 1, Henry VIII, Julius Caesar, King John, Macbeth, Measure for Measure, The Taming of the Shrew, The Tempest, Timon of Athens, Twelfth Night, The Two Gentlemen of Verona, and The Winter’s Tale.

6. The Folio doesn’t actually collect all of Shakespeare’s plays.

Scholars now agree that Edward III, The Two Noble Kinsmen, and Pericles, Prince of Tyre were co-written by Shakespeare, but they are missing from the collection for unclear reasons. Also absent are two plays that are likely lost forever: Cardenio, which is thought to have been based on Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote, and Love’s Labour’s Won, which was probably a sequel to Love’s Labour’s Lost.

There are also a number of plays that Shakespeare might have had a hand in, which are the subject of ongoing academic debate. The list of Shakespeare Apocrypha includes The London Prodigal, A Yorkshire Tragedy, and Sir Thomas More, which some scholars believe even contains Shakespeare’s handwriting.

7. The Folio contains one of only two portraits that definitively portray Shakespeare.

Although there are many portraits of Shakespeare, scholars believe that only two definitely represent him. One is the painted bust on his funerary monument in his hometown of Stratford-upon-Avon. The other is Martin Droeshout’s portrait of the playwright on the First Folio’s title page. In a poem opposite the picture, Ben Jonson, who wrote two flattering poems for the Folio’s front pages, praises Droeshout for capturing the Bard’s likeness, declaring that he “hath hit his face” accurately.

There are actually four different versions of the First Folio portrait because Droeshout added shading and small details after printing had begun; the portrait was updated again 62 years later, by someone unknown, for the printing of the Fourth Folio. Other famous paintings that claim to depict Shakespeare include the Chandos portrait and the Cobbe portrait, but their authenticity is contested.

8. There are 18 front pages preceding the plays.

After the title page, there are two pieces written by Heminge and Condell. The first is addressed to their patrons, brothers William and Philip Herbert, and the second to the Folio’s readers. Four more poems, written by Jonson, Hugh Holland, Leonard Digges, and James Mabbe follow, with Jonson’s featuring the prescient and oft-repeated remark that Shakespeare was “not of an age, but for all time!” Then there is a list of actors who performed the plays and the crucial contents page, after which readers can finally dive into Shakespeare’s plays (starting with The Tempest).

9. One of the First Folios smells like cherries, moldy furniture, and tobacco.

According to Alexy Karenowska, the Director of Technology at The Institute for Digital Archaeology, “no two books smell exactly alike.” Each copy of the Folio smells a little different, but the one housed at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, which probably belonged to 18th-century Shakespeare scholar Edmond Malone, apparently smells like “benzaldehyde, a chemical evocative of maraschino cherries, and 2-nonenal, known as moldy furniture smell to odor experts, but there are also strong traces of tobacco.”

10. Three other editions of the Folio were released during the 17th century.

The success of the First Folio led to the subsequent printing of the Second Folio in 1632, the Third Folio in 1663, and the Fourth Folio in 1685. The second impression of the Third Folio added seven plays to the collection: Pericles, The London Prodigal, Thomas Lord Cromwell, Sir John Oldcastle, The Puritan, A Yorkshire Tragedy, and Locrine. All but Pericles are considered Shakespeare Apocrypha, with Shakespeare’s authorship being questionable.

11. A fraudulent False Folio was printed in 1619—four years before the First Folio hit shelves.

An unauthorized text now known as the False Folio, or the Pavier quartos, was published in 1619. The volume of 10 plays was put together at William Jaggard’s print shop (where the First Folio would eventually come to life) with the help of Thomas Pavier. Jaggard did not have the rights to some of the plays and so printed them with false dates and title pages. Only two copies of the False Folio are known to exist—one is held at the Folger Shakespeare Library and the other at Texas Christian University.

There are also an unknown number of fake Folios that have appeared in the years since the printing of the First Folio; experts typically spot these as facsimiles immediately. Notable instances of forgery usually involve tampering with genuine Folios. For instance, in 1852, Shakespeare scholar John Payne Collier claimed to have discovered a Second Folio, known as the Perkins Folio, with extensive 17th-century annotations that were later proven to be fake. Also during the 19th century, the British Museum hired John Harris to recreate missing pages and repair damage in copies of the First Folio. His work was so skilled that it is now challenging for experts to accurately authenticate copies.