The basic beats of the story behind the Lost Colony of Roanoke go something like this: In the late 16th century, a group of English colonists settled on an island off the coast of modern-day North Carolina, only to vanish (nearly) without a trace within just a few years of their arrival. Their disappearance is one of North American colonial history’s most enduring mysteries, inspiring countless theories and one duly terrifying season of American Horror Story.

Here are 13 facts about the origins and demise of Roanoke Island’s hapless colony—and several theories about where its inhabitants may have ended up.

1. Sir Walter Raleigh kickstarted the exploration of Roanoke Island.

In 1584, Queen Elizabeth I issued Walter Raleigh a sweeping charter to settle any territory that other European nations hadn’t yet claimed. Raleigh himself couldn’t venture across the pond—the queen wanted him to stay at court—but he organized an expedition to scout out a good spot for a settlement in North America. From there, Raleigh hoped to pursue several ventures, from searching for purported gold and silver mines to finding a sailable route to the Pacific Ocean. But his main priority was to establish a permanent post where privateers could restock (and hide out) between attacks on Spanish treasure ships in the West Indies.

So, explorers Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe surveyed what’s now coastal North Carolina and the Outer Banks, a region that the resident Algonquin-speaking tribes knew as Ossomocomuck. Wingina, leader of several local villages, received the Englishmen graciously, and even sent two emissaries, Manteo and Wanchese, back with them to England.

2. Queen Elizabeth I became the region’s namesake.

In his report of the voyage given to Raleigh, Barlowe described Ossomocomuck as “most beautiful and pleasant to behold, replenished with Deere, Conies [rabbits], Hares and divers[e] beasts, and about them the goodliest and best fish in the world, and in great abundance,” not to mention “fertile ground” and woods “full of Corrants, of flaxe, and many other notable commodities.”

Queen Elizabeth was pleased with the results. She allowed the entire territory to be named Virginia, a reference to her status as the virgin queen. She also bestowed a knighthood on Raleigh and gave him additional resources and rights to set up a permanent colony on Roanoke Island, a 10-mile-long and 2.5-mile wide land mass sandwiched between mainland North Carolina and the Outer Banks.

3. The first English attempt at living on Roanoke Island was a failure.

On April 9, 1585, five large ships and two smaller ones set sail from Plymouth, England, with some 600 men aboard, including Manteo and Wanchese (though not Raleigh, who still had to stay home). Sir Richard Grenville, a wealthy privateer who was also Raleigh’s cousin, served as commander; and Ralph Lane, a cousin of Henry VIII‘s sixth wife Katherine Parr, was recalled from a sheriff’s post in Ireland to become Roanoke’s first governor.

Upon their arrival in June 1585, the settlers realized that Barlowe and company had oversold the promise of the territory. For starters, it was extremely treacherous to steer ships through the shallow waters around the Outer Banks, and they had no choice but to anchor the largest vessels far offshore—unprotected from bad weather. In the struggle to find safe mooring, the settlers lost the bulk of their food, and Grenville soon headed back to England to obtain more resources. With him went all but roughly 100 men, who, under Lane’s leadership, got to work building a fort on Roanoke Island.

4. The colonists’ subpar survival skills caused problems.

The Roanoke tribes, ruled by Wingina, were expert farmers whose generosity sustained Lane’s contingent through the winter of 1585. But the relationship unraveled the following spring, probably in large part over the constant pressure to keep the feckless and overbearing colonists fed. When Lane learned that Wingina was apparently mounting a joint attack with other tribes, he and his men struck first, killing Wingina (among others) in early June 1586.

The colonists’ survival chances would have been dire had not Sir Francis Drake happened to stop by days later, hot off a privateering marathon in the Caribbean. When a storm blew through, damaging some of Drake’s fleet and depleting resources he’d offered to the colonists, the beleaguered settlers decided their best bet was to just sail home with him.

Meanwhile, Grenville had been accumulating supplies for the Roanoke settlement and set out for the island in April 1586. The voyage was prolonged by his penchant for raiding whatever ships he came across along the way, and the fort was already deserted by the time the fleet arrived in the summer. Grenville left 15 of his men to look after the settlement while he and the rest of his forces departed.

5. A second group of settlers sailed to Roanoke—but they didn’t intend to stay there.

The initial attempt at a settlement on Roanoke Island showed pretty decisively that the Outer Banks lacked suitable ports. But Lane’s men had explored enough of the area to suggest an alternative about 100 miles to the north: the Chesapeake Bay, fed by deep rivers that would make for ideal harbors. From there, colonists could also hunt for lucrative metal mines they’d heard about from the Native Americans—and maybe even a passage to the Pacific Ocean.

Three more ships, under the command of a seasoned Portuguese skipper named Simon Fernandez, departed England for North America on May 8, 1587. The plan was for passengers to briefly stop at Roanoke to touch base with Grenville’s remaining men at the abandoned fort. Then, the 115 or so emigrants—this time including women and children—were supposed to establish a permanent settlement somewhere in the Chesapeake Bay area.

6. Things did not go as planned.

When the colonists arrived at Roanoke in July, however, Fernandez made it clear that he had no intention of ferrying the colonists farther north as planned. The only surviving account of the decision comes from passenger John White, the new colony’s intended governor, who reported that Fernandez and his cohort were impatient to fit in some quality privateering in the West Indies. But it’s also possible that Fernandez was worried the colonists wouldn’t fare well against the Chesapeake Bay tribes, who had attacked Europeans in the past. Whatever the case, White didn’t push the matter further and simply prepared to settle at Roanoke.

Uncertainty plagued the new immigrants almost immediately, as Grenville’s party did not greet them at the fort; instead, they found only a single human skeleton and the rest of the property deserted. Several days later, a group of Native Americans killed a newly arrived colonist named George Howe while he fished for crabs.

7. The colonists’ warm relationship with the Native peoples was cooling off.

Though John White’s party of English colonists was basically stranded on Roanoke Island, they weren’t completely friendless. They had a solid ally in Manteo, who had journeyed back to England with the previous party and returned to Roanoke with White’s expedition. He was the son of a woman generally believed to have been chief of the Croatoans, who lived on Croatoan Island (now Hatteras Island). They told the colonists that Howe’s assailants—Wanchese among them—were from a Roanoke tribe, and most of Grenville’s men had been killed by a coalition of three Native groups. (The fate of the survivors is still unknown.)

Ralph Lane‘s murder of the chief Wingina the previous year had pretty much guaranteed that these new colonists would be on their own. And while the Croatoans themselves were more or less friendly toward the trespassers, they also stressed that they didn’t have enough food to share. The colonists further strained the relationship by ambushing a Roanoke village in retaliation for Howe’s death—but the original occupants had recently deserted it, and the victims of the attack were actually innocent Croatoans who’d gone there to collect leftover food.

8. Amid the turmoil, Virginia Dare became the first English child born in North America.

August 18, at least, was one bright spot during an otherwise contentious time. On that day, White’s daughter, Eleanor Dare, and her husband, Ananias Dare, welcomed a daughter: Virginia Dare. She was the first English child ever born on American soil.

The only thing we know about Virginia is that she was baptized on August 24, and we don’t know much about her parents, either. Ananias was a tiler and bricklayer who married Eleanor at St. Bride’s Church in London. It’s been suggested that the couple and other Roanoke colonists may have moved to the New World in pursuit of religious freedom, but the truth remains a mystery. Considering that John White had personally persuaded some of the colonists to make the journey, it seems safe to assume that his encouragement factored into his son-in-law and daughter’s decision to accompany him. Ananias was named one of the 12 official “assistants” to White.

9. John White found it hard to leave Roanoke—and even harder to make it back.

The colonists, believing that Governor White was best suited to wrangle much-needed supplies for the settlement‘s survival, implored him to leave with Fernandez for England in August 1587. White resisted, mainly because he felt that going home so soon would cause people to think poorly of him for abandoning his charges, some of whom he’d personally urged to make the trip. He was also really worried that, while he was gone, the colonists would steal his “stuffe and goods.”

But the men and women persisted, promising to safeguard his belongings and even drafting a contract to state that they had “most earnestly intreated, and incessantly requested” him to go. At last, he relented.

His return voyage was initially delayed by the Anglo-Spanish War: Elizabeth I had essentially ordered all ships to be on call for the conflict. He got the go-ahead to sail two modest vessels back to Roanoke in April 1588, but was forced to turn back after being attacked by French privateers. Financing a follow-up relief mission took a while, and he didn’t set foot on Roanoke until August 1590.

10. By the time White returned, all the colonists had vanished.

White never saw his daughter, his granddaughter, or any other English resident of Roanoke again. When he and his companions arrived at the fort, they found no signs of the colonists’ presence. There were, however, plenty of signs that the colonists had packed up everything they could carry and left in an organized fashion—and not too recently. The houses had been “taken down,” White recounted, and there were iron bars and other “such like heavie things, throwen here and there, almost overgrowen with grasse and weedes.”

The colonists had also buried chests of items, which had been “long sithence digged up againe and broken up,” which White attributed to the Roanoke Native Americans. Among these scattered remnants were many of his own cherished belongings, from rain-ruined maps and books to rusty armor. White wrote that he was “much grieved … to see such spoyle of my goods.”

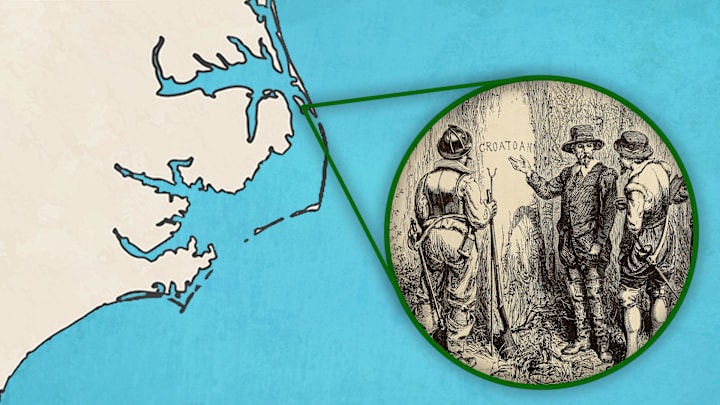

11. The missing colonists left two written clues regarding their whereabouts.

White also found two written clues: the letters CRO carved into a tree trunk, and the word CROATOAN etched into a wooden post at the entrance of their fort. To many people today, these are the most mysterious details from the story of Roanoke’s lost colony. To White, they didn’t seem all that mysterious.

Prior to his departure in 1587, he and the colonists had devised a plan: They were supposed to head 50 miles onto the mainland—presumably to establish a more permanent city, as was originally planned—making sure beforehand “to write or carve on the trees or posts of the doors the name of the place where they should be seated.” White had also instructed them to carve a cross over the name of the place “if they should happen to be distressed.” In the absence of any cross, White wrote that he was “greatly joyed” at having located “a certain token of their safe being at Croatoan.”

He couldn’t sail immediately to Croatoan Island, however: White’s vessels had been damaged in a violent storm, and he decided to withdraw to safety and recuperate. He had hoped to privateer his way through the West Indies all winter and then return to reunite with the colonists, but another storm forced him east, and he ended up charting a course for the Azores—an archipelago about 950 miles off the coast of Portugal. By that fall (1590), White was on his way back to England.

It’s unclear why he ultimately decided against returning to Roanoke during that trip. In her book Roanoke: The Abandoned Colony, Karen Ordahl Kupperman suggests that perhaps the resources in the Azores wouldn’t meet Roanoke’s needs, or that White’s crew was anxious to be back in England to ensure their fair shares of the profits from a Spanish ship they’d raided en route to Roanoke.

12. Clues to the Roanoke colony’s possible fate emerged from witnesses in another English colony.

Despite the large number of missing people, few rescue missions were dispatched. As Kupperman explains, “The overwhelming need to have each venture pay its own way tended to swamp all other considerations.” In other words, even a vessel that aimed to locate the colonists was liable to forgo the effort in favor of looting any passing Spanish ship.

But hints about the fate of the colonists did come to light as England made a more concerted effort to colonize the area in the early 17th century. In the vicinity of the Jamestown colony, Captain John Smith reported in 1608 that Powhatan had said he’d seen “people with short Coates, and Sleeves to the Elbowes” (i.e. European clothing). Smith’s fellow Jamestown settler George Percy wrote of glimpsing a 10-year-old Native American boy with “a head of hair of a perfect yellow” and “white skin” while sailing up Virginia’s James River. Another Jamestownian, William Strachey, alleged that Powhatan had “miserably slaughtered” all but a handful of Roanoke colonists after they’d “peaceably lyved intermixt” with Native Americans in the Chesapeake region for about 20 years.

13. The colonists may have assimilated into Native American communities.

In his 1709 book A New Voyage to Carolina, English explorer John Lawson wrote that the “Hatteras Indians” told him “several of their Ancestors were white People … the Truth of which is confirm’d by gray Eyes being found frequently amongst these Indians, and no others.” This would jibe with the colonists’ CROATOAN message. As for the aforementioned sightings of white people among more northern Native Americans, historian David Beers Quinn posited that perhaps most of the colonists headed toward the Chesapeake Bay, leaving behind a small group that could guide John White to the new spot upon his return; and that group, per Quinn’s theory, ended up relocating to Croatoan Island for safety purposes.

Scholars continually debate the truth of each historical account and the merits of every hypothesis. Even archaeological evidence of English settlers in a given location has proven tough to tie to the Roanoke colonists, as it could have belonged to later settlers or been traded to (or salvaged by) Native Americans. In short, all we really have are theories—and a mystery that still tantalizes us nearly 450 years after the events took place.