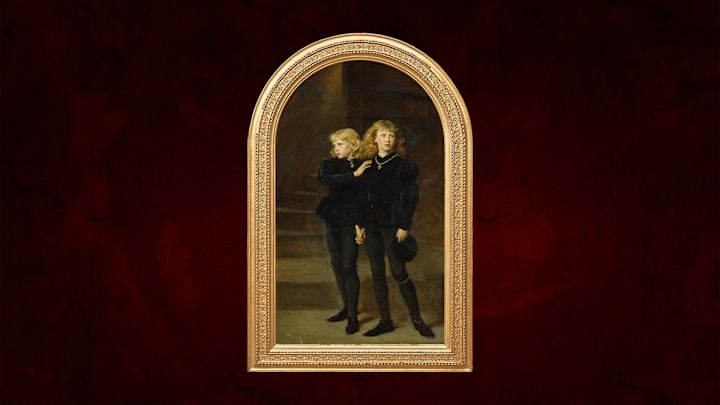

During the early summer of 1483, England’s bonny young princes, Edward and Richard, could often be found outside, shooting their bows and arrows with abandon and gambolling around the way kids always do in their own backyards.

But these kids weren’t in their own backyard: They were in the garden of the Tower of London, playing against the backdrop of a bloody and tediously long tug of war for the throne. What began as their refuge would soon become their prison, and they’d never be seen beyond the walls of the fortress again.

More than half a millennium later, royal history buffs are still tantalized by the mystery of the brothers’ disappearance—one whose solution may lie in Westminster Abbey at this very moment. Here’s the whole captivating story of the so-called “princes in the tower.”

Say Uncle

The princes in the tower were the only two sons of King Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville: Edward V and his younger brother, Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York. They were 12 and 9 years old, respectively, when their father died in April 1483. Before his death, he named his brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, as Lord Protector of Edward V.

When Richard met up with Edward V’s maternal uncle Anthony Woodville and half-brother Richard Grey, who were bringing the young king to London, he arrested them and their companion Thomas Vaughan—evidently because he feared being usurped by the Woodville family. (He had the three executed a couple months later.)

By mid-May, Richard had installed Edward V in the Tower of London for safety purposes, which seemed logical enough. This was during the War of the Roses: a decades-long struggle for the throne between the House of York (which included Richard III and Edward IV, among others) and the House of Lancaster (starring Henrys IV, V, and VI). Plus, plans for Edward V’s coronation were in the works, and a soon-to-be-crowned monarch typically stayed in the Tower of London leading up to the ceremony, anyway. In mid-June, Richard relocated Edward V’s younger brother from his mother’s care at Westminster Abbey to the Tower of London, too [PDF].

Despite all the talk about keeping Edward V in the tower for his own safety, it quickly became clear that Richard’s endgame wasn’t to see his brother’s heir securely enthroned. In June, Parliament proclaimed that because Edward IV once had a pre-contract to marry Lady Eleanor Butler but had secretly married Elizabeth Woodville instead, his children with the latter weren’t legitimate heirs. Weeks later, on July 6, Richard himself assumed the throne as King Richard III.

What happened to the two princes after that is one of the biggest mysteries in British royal history. Contemporary reports are exceptionally rare, and it’s hard to nail down exact dates for a number of events in the timeline. According to Dominic Mancini, an Italian monk who was at court during this time, things started to go downhill for the princes after Richard executed Baron William Hastings—a trusted friend of Edward IV who had actually helped install Richard as Lord Protector—for treason in mid-June. Why their relationship soured is up for debate, but the leading theory is that Hastings, as a defender of Edward V’s right to rule, stood in the way of Richard’s plot to seize the crown. After Hastings’s death, per Mancini, “all the attendants who had waited upon [Edward V] were debarred access to him.”

“He and his brother were withdrawn into the inner apartments of the tower proper, and day by day began to be seen more rarely behind the bars and windows, till at length they ceased to appear altogether,” Mancini went on. “The physician Argentine, the last of his attendants whose services the king enjoyed, reported that the young king, like a victim prepared for sacrifice, sought remission of his sins by daily confession and penance, because he believed that death was facing him.”

There’s also a royal record of wages paid to 13 men for working in service of “Edward bastard, late called King Edward V” from July 18. And according to The Great Chronicle of London, the princes “were seen shooting and playing in the garden of the tower by sundry times” (sundry meaning “various”) sometime during Edmund Shaa’s tenure as lord mayor of London from October 1482 to October 1483.

All we can really glean from those sparse sources is that, while the princes were originally well cared for and free to be outside, their confinement in the tower morphed into flat-out imprisonment as their uncle assumed power. Mancini departed London in mid-July, so this evolution must have happened before then.

The Primary Suspects

The simplest explanation is that Richard III had his nephews murdered so they’d never threaten his hold on the throne. There were rumors about this theory during Richard’s reign; The Great Chronicle reported that “after Easter [1484] there was much whispering among the people that the king had put the children of King Edward to death.”

Richard III had reason to be worried about getting ousted, and not just by those hoping to restore Edward V to power—after all, the War of the Roses was still raging. In October 1483, Richard III’s former ally Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, staged a Lancastrian rebellion to replace the king with the exiled Henry Tudor. It failed (and Stafford was beheaded), but it’s been suggested that Stafford may have assassinated the two princes around this time so they wouldn’t threaten Henry Tudor’s claim to the throne—and maybe also so the public would blame Richard for the murders.

Another theory is that Stafford killed the princes as a way to ingratiate himself with the king before their rift and the ensuing rebellion. Even if Stafford himself dealt the death blows, though, it would hardly absolve Richard of all involvement. According to Jeremy Potter’s book Good King Richard? An Account of Richard III and His Reputation, historians believe that Stafford “would never have dared to act without Richard’s complicity or, at least, connivance.”

Henry Tudor himself is also on the suspect list. He became King Henry VII after Richard III died during the Battle of Bosworth in August 1485, and he married the princes’ eldest sister, Elizabeth of York, the following year. This union of York and Lancaster effectively ended the War of the Roses, and Henry VII ensured that Edward IV’s children were reinstated as legitimate heirs—solidifying his wife’s own claim to the throne. Should either of her brothers ever show up, though, his claim (as a male heir) would outrank hers. Some people believe Henry VII may have had the princes murdered to prevent that from ever happening.

But Richard III prevails as the prime suspect in part because history is written by the victors, and the Tudor dynasty vilified him. In The History of Richard III, penned during Henry VIII’s reign, author Thomas More paints a portrait of the princes’ murders by agents of Sir James Tyrrell, acting on orders from Richard III.

“[This] Miles Forest and John Dighton about midnight (the sely children lying in their beds) came into the chamber and suddenly lapped them up among the clothes so bewrapped them and entangled them, keeping down by force the featherbed and pillows hard unto their mouths, that within a while, smored and stifled, their breath failing, they gave up to God their innocent souls into the joys of heaven, leaving to the tormentors their bodies dead in the bed,” More wrote.

It’s tempting to take such a compelling and detailed account at face value—even Shakespeare borrowed from it—but historians have pointed out that More was significantly biased toward the Tudors and was writing some 30 years after the alleged crime. Not to mention the general lack of evidence to back up his story.

It’s also tempting to hold out hope that the princes escaped. In the years after their disappearance, two unrelated men each claimed to be one of the missing heirs; and while both were written off as imposters—one copped to being a boatman’s son, and the other started impersonating a different royal nephew—some people still believe otherwise. But there is circumstantial evidence suggesting that the princes may indeed have perished during their internment in the Tower of London.

Where Are the Princes Now?

In 1674, during Charles II’s reign, laborers unearthed two child-sized skeletons buried 10 feet beneath a staircase in the Tower of London’s White Tower. At the time, people assumed that these were the princes’ remains, and they’re kept to this day at Westminster Abbey in an urn labeling them as such. (The inscription also states that the boys were “stifled with pillows” and “meanly buried … by the order of their perfidious uncle Richard the Usurper.”)

In 1933, the remains were analyzed and determined to likely be the princes, though a number of later-20th-century experts disputed the conclusions made in that report; we don’t even know, for example, that the victims were definitely male. The only thing scholars generally agree on is that the pair were around the princes’ ages when they died. But that hardly proves their identity—and besides, they’re not the only children’s bones that have been found in the tower. As A.J. Pollard put it in his book Richard III and the Princes in the Tower, “The fact is that there are many skeletons in the tower’s cupboard.”

There’s a reason the remains in the urn haven’t been subjected to more modern forensic analysis: The Church of England has denied requests to try it. In 2013, The Guardian reported on newly revealed correspondence from the 1990s that helps explain why. Basically, the authorities didn’t think the prospect of positively identifying the remains as the princes was worth opening a whole can of worms.

For one thing, it wouldn’t solve the mystery of who killed them, and Westminster Abbey dean Michael Mayne balked at the “great deal of sensational speculation” the endeavor would generate. And if they weren’t the princes, Mayne said, “what do we do with the remains? Keep them in the urn in the royal chapels, knowing they are bogus, or re-bury them elsewhere?”

That kind of logistical concern seems trivial, but it’s related to a larger issue that Mayne also spelled out: “There are others buried in the abbey whose identity is somewhat uncertain, including Richard II, and allowing these bones to be examined could well set a precedent for other requests. I do not believe we are in the business of satisfying curiosity, or of certifying that remains in the abbey tombs are what they are said to be.”

Though Queen Elizabeth II agreed to keep the case closed, there’s always hope that King Charles III is more interested in the business of satisfying curiosity: Sources have claimed that he’s amenable to letting experts retest the remains. Until then, this is one maybe-murder mystery that will stay unsolved.

Read More Stories About British Royal History: