It’s virtually every musician’s dream to have a world-renowned name that can move millions of records and sell out arenas when it’s emblazoned on a marquee. The lucky few who reach that level have to work for years or decades before they get there—but for most, it never happens at all.

In 1993, few entertainers had the name recognition of Prince. But despite all the years and toil it took to arrive at that position, the singer no longer wanted any part of it. Instead, he wanted to be known as something unpronounceable.

Identity Crisis

Prince was born Prince Rogers Nelson in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on June 7, 1958, and had emerged as one of music’s biggest stars in the 1980s. Albums like 1984’s Purple Rain and 1989’s Batman soundtrack were gateways to his eclectic, multifaceted talents. He could sing, play instruments, and put on an electric live show that few could match. He was also tireless when it came to his music production, with a rumored 500 tracks sitting in his “vault” waiting to be released.

But Warner Bros., the label behind Prince, saw the singer’s prolific output as a potential problem. He was already averaging one album per year by the early 1990s, and the record company believed that his desire to release so much material might create consumer fatigue. It was the same kind of thinking that led Stephen King to create his Richard Bachman pseudonym in order to satisfy his creative impulses. But Prince couldn’t hide behind a pen name on stage, so he pled with the label to release his backlogged music even while the company was still promoting his last album.

“I would tell him that it was counterproductive, that people can only absorb so much music from one artist at a time,” Warner executive Marylou Badeaux said in 2016. “His answer was, ‘What am I supposed to do? The music just flows through me.’”

His strained relationship with the label was chafing him. His own given name had been trademarked by the company, which increasingly had him feeling like a commodity. The intersection of business and creativity was stifling, and not even the reported $100 million price tag attached to his latest deal seemed to satisfy him. The pact called for one album per year; Prince spoke of wanting to release albums whenever the mood struck, whether it was 12 songs or 70.

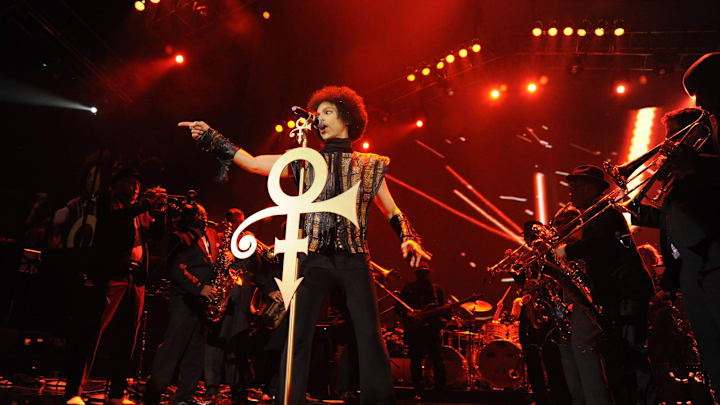

In 1992, Prince believed he had come up with a solution. While recording music at his Paisley Park estate in Minnesota, the singer had an idea to create a graphic that fused the astrological symbols for men (Mars) and women (Venus). He asked an intermediary to put the request to HDMG, a studio that was already creating designs for his albums. HDMG employees Mitch Monson and Lizz Luce then sketched several concepts, one of which Prince picked out. (The Love Symbol, as it came to be known, was slightly off-center at the singer’s request.)

The designers had little idea what Prince had in mind for the symbol beyond its use for his 14th studio album, known as The Love Symbol Album. Then in 1993, on his 35th birthday, the singer issued a press release notifying media and fans that he had changed his name to the same symbol—an unpronounceable glyph that looked equal parts Egyptian and musical note.

“It is an unpronounceable symbol whose meaning has not been identified,” the artist wrote. “It’s all about thinking in new ways, tuning in 2 a new free-quency.”

Sign of the Times

The symbol wasn't really a legal solution to Prince's contract issues, although that may have been part of his motivation.

“In Prince's mind, by changing his name to a symbol, he thought he could rescind and void the contract,” the singer’s then-lawyer, Londell McMillan, told 20/20 in 2016. “Because he was no longer a signatory under the name Prince Rogers Nelson. We now know that was not the case. However, it was still a very bold, courageous, and clever move on his part.”

Prince didn't change his name legally—this was simply an adoption of a new stage name, or symbol, that highlighted his dissatisfaction with the record industry and Warner in particular. But while he couldn’t get out of any legal obligations, he still wanted to be addressed differently from then on.

“[He] insisted that we use that as the reference to him,” McMillan said. “So, in my computers, at the time, we had to download the font. And I had to actually use the font to describe Prince.” McMillan also avoided calling him “Prince” to his face.

Warner, of course, still had an artist to promote—one with a very lucrative deal. The label sent out thousands of computer floppy disks to media outlets to help them depict the symbol, as it wasn’t able to be replicated on conventional keyboards.

Naturally, fans and industry observers who have been informed of a name change that’s unpronounceable and not able to be typed found the idea somewhat obnoxious. MTV used a metallic clanging noise in place of the singer’s name on air; record sales went down. Eventually, Warner and Prince agreed that referring to him as the Artist Formerly Known As Prince was a reasonable compromise, though Prince was still feeling restricted. In 1995, he appeared on stage with the word slave written across his cheek.

By 1996, the singer’s deal with Warner had expired. This seemed to placate Prince, who later resumed using his birth name and released music as he saw fit while operating as an independent artist. But his animosity toward Warner appeared to ease with time. In 2014, two years before the singer’s death, he partnered with the label to reissue Purple Rain for its 30th anniversary.

A full explanation of the name change was, according to Rolling Stone writer Neal Karlen, typed up and placed in a time capsule on the grounds of the singer’s estate in Minnesota, where it has yet to surface. Like most things related to Prince, the explanation wasn’t as important as the execution.