Unicorns, mermaids, vampires, and leprechauns are some of the most widely known mythical creatures, but where did these legendary beings come from? We attempt to get to the bottom of the origins of those creatures and more in this list adapted from The List Show on YouTube. (Don’t forget to subscribe to Mental Floss for new videos every week!)

1. Unicorns

In the 4th century BCE, Greek physician Ctesias described a strange animal. It was large, fast, and strong, with a white body, a red head, and dark blue eyes. It also had a roughly two-foot-long horn—white on the bottom and black in the middle, with a crimson red tip—growing from its forehead.

Catching the creature was nearly impossible, unless it could be cornered near its young—then, it wouldn’t flee, but instead, Ctesias wrote, would “butt with their horns, kick, bite, and kill many men and horses. They are at last taken, after they have been pierced with arrows and spears; for it is impossible to capture them alive.”

Ctesias called the animal a “wild ass,” but today, we consider this passage the first written description of a unicorn.

Single-horned creatures occur in folktales—some of them thousands of years old—in cultures around the world. In European accounts, the unicorn is a white, horse- or goat-like animal with cloven hooves and a long, spiraled horn. Similar creatures are found in Asian folktales, including—depending on the particular depiction—the qilin, a deer-like animal with the scales of a dragon and, at times, a single horn.

For quite some time, people believed unicorns weren’t actually myths, but real-life animals. Pliny described an animal he called monokeros—or “single horn”—which he wrote had “the head of the stag, the feet of the elephant, and the tail of the boar, while the rest of the body is like that of the horse; it makes a deep lowing noise, and has a single black horn, which projects from the middle of its forehead.”

Later, Marco Polo—who believed he had laid eyes on the creatures himself—wrote that unicorns were “very ugly brutes to look at” and could be found “wallowing in mud and slime.” In the 1500s, Conrad Gesner featured a description and illustration of the animal in an edition of his natural history text—History of the Animals in English—and like Ctesias and Pliny before him, he based his account on descriptions from explorers, not an actual specimen or an animal he saw himself. But for people of the Middle Ages, there was no doubt that these animals were real: Sailors and merchants even peddled long, white, spiraled horns that they said came from the creatures. Drinking from cups made of the horns was said to protect against disease and poison.

The belief that unicorns were real persisted until the 18th century. But as travelers made their way to increasingly far-off lands and found no actual unicorns, that started to change. Today, scientists believe that the early descriptions of unicorns were real animals that explorers had no reference for at home, including oryxes and rhinos. Those unicorn horns probably came from rhinos or narwhals (whose horn is actually a big ol’ tooth, by the way).

2. Merpeople

Hans Christian Andersen’s little mermaid—and the exceptionally more cheerful Disney cartoon she inspired—is probably the most famous merperson of all time, but tales of half-human, half-fish creatures go back as far as ancient Mesopotamia, and are present in legends from cultures around the world. Slavic mythology, for example, has the Rusalka, which is said to be the spirit of a virginal woman or an unbaptized child; tales from Western, Central, and Southern African cultures feature Mami Wata, a water spirit that is often portrayed as part mermaid, part snake charmer. These myths, incidentally, might themselves have been influenced by Andersen’s famous story.

Depending on where she’s coming from, a mermaid might represent good luck, fertility, or the dangerous and unpredictable nature of the ocean—so for sailors, spotting one of the creatures could either be a good sign or a bad one.

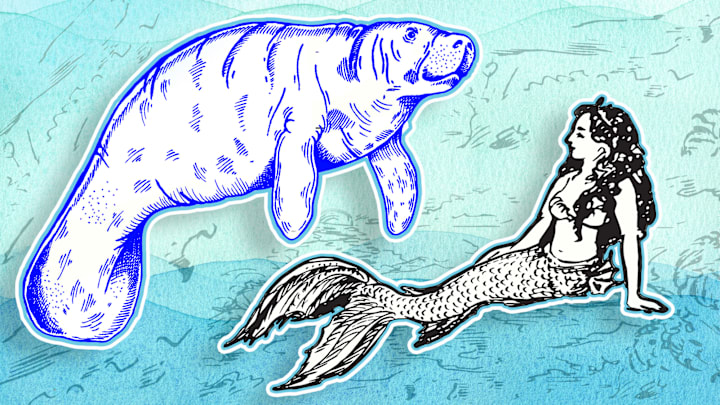

When Christopher Columbus saw what he believed to be a group of mermaids, he said that they were “not half as beautiful as they are painted, though to some extent they have the form of a human face.”

Spoiler alert: They weren’t mermaids. They were manatees. Scientists suspect the sea cows and their relatives, as well as seals, are responsible for most mermaid sightings reported by sailors.

3. Sirens

Whatever you do, don’t confuse mermaids with sirens—though they have been conflated, they’re not the same thing. Sirens were half-women, half-bird creatures from Greek mythology that ruthlessly lured sailors to untimely deaths with their song. According to Britannica, one theory is that these creatures “seem to have evolved from an ancient tale of the perils of early exploration combined with an Asian image of a bird-woman. Anthropologists explain the Asian image as a soul-bird—i.e., a winged ghost that stole the living to share its fate.”

4. Pontianak

Enough with the stories about vengeful half-woman creatures who lure men to their deaths just because—let’s talk about a spirit from South Asian folklore who has a very good reason for what she does.

In Malaysia, a woman who has endured suffering during death—whether it occurs in childbirth or at the hands of a man—is sometimes said to become a spirit called Pontianak. Dressed all in white, with long, dark hair and smelling like the frangipani flower, the Pontianak wanders at night, exacting revenge by, in some versions, disemboweling a man with her nails. Then she eats his guts.

As Sharlene Teo, who wrote the novel Ponti, inspired by the spirit, told VICE, “The pontianak mimics vulnerability and seeming gentility through her high-pitched baby cries and frangipani scent, but try and take advantage of her and she’ll suck your eyeballs out.” In other words: Don’t mess with her.

The Indonesian counterpart of this mythical being is the Kuntilanak, but it’s difficult to say where the stories first arose. Related spirits pop up in Bangladesh, India, and Singapore, for example.

There’s an Indonesian city named Pontianak, but unfortunately for our purposes that doesn’t necessarily provide an explanation for the myth. The city actually takes its name from the spirit, and not the other way around. According to legend, the area was infested with the ghosts until the city’s founder and his men drove them out.

One thing we do know is that horror movies helped spread these stories. Movies and TV shows about Pontianak have been made since at least the 1950s.

5. Werewolf

As it turns out, the werewolf might be as old as, well, literature itself. One version of The Epic of Gilgamesh features a story about a woman who turned a former paramour into a wolf. Men who turned into wolves also popped up in the mythology of Ancient Rome and Greece. As Tanika Koosmen pointed out in a piece for The Conversation, Herodotus wrote about a tribe of people from Eastern Europe who, he was told, transformed into wolves at certain times of the year. According to Koosmen, “Using wolf skins for warmth is not outside the realm of possibility for inhabitants of such a harsh climate: this is likely the reason Herodotus described their practice as ‘transformation.’”

6. Vampires

Stories about demons that survive by sucking the bloody life force from humans have been around for millennia, but modern vampires are way more recent than you probably think: In fact, the word vampyre only pops up in the English written record around the turn of the 18th century. (Perhaps the earliest extant reference actually referred to vampires metaphorically in the context of business practices, suggesting the concept was already familiar to readers. That book, Observations of the Revolution of 1688, was written right around the time of that revolution but not published until the mid 1700s.)

Deborah Mutch writes in The Modern Vampire and Human Identity that “Western Europeans became interested in the phenomenon of the vampire during the late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries as reports emerged from Eastern Europe of a series of vampire ‘epidemics.’”

So what was causing these epidemics of vampirism? Modern science has some ideas, most of them leading back to real-life diseases: Porphyria causes light sensitivity. Rabies is associated with biting and hypersensitivity to things with strong aromas—like, for example, garlic.

The introduction of corn into European diets around this time may have played a role in spreading vampire myths. Europeans who ate the un-nixtamalized version of the grain often ended up with dietary deficiencies, leading to widespread bouts of pellagra. One symptom of that disease is also light-sensitivity.

Decomposition might have also played a role. The bodies of suspected vamps were often dug up, and as the skin shrinks during decomposition, it would have appeared as though the hair and nails of the deceased had continued to grow after death. This may have led to the assumption that the corpse wasn’t quite so dead after all.

Eastern Europe was going through extreme social and cultural upheaval at the time, which—as we discussed in our episode about mass hysteria—is a prime driver for these kinds of epidemics.

These days, pop culture depictions of vampires show the creatures being created by a bite; sometimes, the mutual drinking of blood is necessary. Bites were certainly a part of traditional vampire lore as well, but they weren’t the only way to create a bloodsucker: In certain myths, all it took for someone to rise again was for an animal to jump over the corpse. In Slavic regions and in China, it was usually a dog or a cat doing the jumping, but in Romania, a bat flying overhead was said to reanimate a dead body.

7. Zombies

Thanks to pop culture, we tend to think of zombies as undead flesh-eaters that are especially hungry for braaaaaains. We have George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead to thank for some of that, but not the bit about brains—that comes from the 1985 movie Return of the Living Dead, in which zombies were said to snack on gray matter because it took away the pain of being dead.

That is all a far cry from the zombie’s Haitian origins. According to folklore, zombies are dead bodies revived by voodoo priests called bokors. Once out of the grave and reanimated, the zombie is under the bokor’s control.

The slave trade may have brought these beliefs from West Africa to Haiti, but once in the New World, they evolved. In fact, as journalism professor and Farewell, Fred Voodoo: A Letter From Haiti author Amy Wilentz wrote in a New York Times op-ed in 2012, zombies are “a New World phenomenon that arose from the mixture of old African religious beliefs and the pain of slavery.”

It’s an understatement to say that the lives of enslaved people were horrifically brutal. For most, death was the only way out. According to some Afro-Caribbean traditions, a natural death allowed their now-free souls to return to Africa, or, more specifically, an guinée, or “Guinea.” Mike Mariani writes in The Atlantic that “The original brains-eating fiend was a slave not to the flesh of others but to his own. … Though suicide was common among [enslaved people], those who took their own lives wouldn’t be allowed to return to lan guinée. Instead, they’d be condemned to skulk the Hispaniola plantations for eternity, undead slaves at once denied their own bodies and yet trapped inside them—soulless zombies.”

As horrific as that mythology is, it’s worth pointing out that for some, zombies aren’t a myth at all, but a real phenomenon—and there is at least one documented case that seems to support this belief: In May 1962, a man named Clairvius Narcisse, who was suffering from a mysterious illness, died in a hospital in Haiti. His death certificate was signed by two doctors, and he was buried. But in 1980, he came back to his hometown and approached his sister, saying that he had been turned into a zombie following an inheritance dispute with his brother. He described hearing his sister weep at his bedside after his death and recounted being buried.

Narcisse’s story was studied and featured in ethnobotanist Wade Davis’s book The Serpent and the Rainbow, which posits that zombies are created using powders laced with tetrodotoxin—a poison that can cause paralysis, derived from the gonads of pufferfish.

8. Leprechaun

Fun fact: Googling the phrase leprechaun origins will not get you what you need to know about where leprechauns come from, but instead everything you never knew you needed to know about the 2014 movie Leprechaun: Origins. Getting the real story requires following the research rainbow right to a pot of gold, a.k.a., a piece on IrishCentral.com by Sean Reid, an employee at the National Leprechaun Museum in Dublin. Reid writes that the first time a leprechaun appears in the written record seems to be the Old Irish tale “The Saga of Fergus mac Léti.” Fergus was the king of Ulster, and according to legend, he was taking a snooze on the beach when some water sprites called lúchorpáin came out of the ocean and tried to drag him in. The shock of the cold water woke Fergus up; he captured the sprites and made them a deal: He’d set them free if they granted three wishes. They agreed, and the leprechaun tale was born. Maybe.

Some sources look further back. In 2019 there were headlines around the globe connecting leprechaun legends to Ancient Rome. A team from the Cambridge University and Queen’s University Belfast discussed the Luperci, a group who probably ran around the ancient city naked during the Lupercalia festival.

In the 5th century CE, St. Augustine mentioned the Luperci in an aside while talking about a lake that supposedly temporarily turned people into wolves. The authors of that 2019 paper think that this got misread, in Ireland, to suggest that the Luperci themselves weren’t humans. Over time, the paper posits, the wolves were dropped from the story and the group became associated with a different water sprite that was thought of as being very small. That all may have combined to eventually create the modern leprechaun.

By the way, these days leprechauns are usually portrayed as crafty cobblers who love gold, pranks, and the color green, but in early tales, they actually preferred to wear red.

9. Dragons

Like many of the creatures on this list, accounts of dragon-like beings go way back: They show up as giant serpents in Mesopotamian art, appear in the realm of the dead in ancient Egyptian mythology, spit venom in Ancient Greek tales, and symbolized good fortune in Chinese folklore. Interestingly, according to Smithsonian magazine, these myths evolved independently around the world. One theory for why that is is that real-life animals—from dinosaur fossils to Nile crocodiles to whales—were misidentified in a pre-Google world.

Speaking of whales, they may have served as inspiration for more than just dragons. One part of them, anyway. At least some of the sea monsters spotted by sailors throughout history were likely whale penises, which can, after all, be upwards of eight feet long.

10. Cyclops

If there’s anything we’ve learned so far, it’s that many mythological creatures probably had a basis in real animals. Cyclops, the famous one-eyed giants of Greek mythology, might be another example. They may have been inspired by the discovery of bones belonging to a relative of the modern day elephant. These creatures were up to 15 feet tall, had 4.5-foot-long tusks, and their skulls featured a single, prominent hole. Today we know that hole was for the animal’s trunk, but Ancient Greeks may have believed it was for one huge eye.

That being said, many experts are unconvinced, with classics professors Mercedes Aguirre and Richard Buxton pointing out that theories like this often have satisfyingly logical explanations, but lack tangible evidence.

11. Griffins

Similar to the Cyclops, Griffins—creatures commonly described as having a lion’s body, eagle’s head, and wings—may have been inspired by the bones of Protoceratops dinosaurs, which had beaks and long shoulder bones that might have been confused for wings. Their skeletons have been found in the Gobi desert, where, according to Greek mythology, griffins guarded their hoards of gold. That’s the theory posited by folklorist Adrienne Mayor, who told The New York Times in 2000 that “I have discovered that if you take all the places of Greek myths, those specific locales turn out to be abundant fossil sites. But there is also a lot of natural knowledge embedded in those myths, showing that Greek perceptions about fossils were pretty amazing for prescientific people.”

As with the cyclops origin story, though, the story makes a certain amount of sense, but it seems to lack rock solid evidence. Paleontologist Mark Witton points out that, though certain key features of griffins would show up in protoceratops fossils, plenty of other parts of those fossils would be difficult to connect to the myths.

12. Cait Sìth

The Scottish Highlands are said to be home to the Cat Sìth, or Fairy Cat, a dog-sized feline with a white patch on its chest. According to legend, the Cait Sìth can steal the souls of the recently deceased, but the people of the Highlands had at least one powerful tool at their disposal to distract the Cait Sith—catnip.

Many think this critter is inspired by the very real Scottish wildcat, or possibly the Kellas cat, which may or may not be a hybrid between the Scottish wildcat and black cats.

13. Yule Cat

The Jólakötturinn, or Yule Cat, is a giant black cat (it’s bigger than a house) from Icelandic folklore that basically exists to get kids to do their chores. According to tradition, children who have finished all their work and done all their chores before Christmas will be rewarded with new clothes; if they’re lazy, they won’t get new clothes, but they will get eaten by the Yule Cat, who goes around Iceland on Christmas night, looking through windows for fancy new duds.

This myth may have come about as a way to encourage productivity during the winter months. In pre-industrial Iceland, when chores needed to get done before the holidays, the Yule Cat might have just served as a handy reminder of the importance of doing your work on time.