The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic in late 2019 was pretty awful—but it also presented a rare moment when a completely new disease came to light. Other illnesses have been with us for hundreds or thousands of years, long before they were identified and treatments were discovered. Here are six that must have baffled ancient physicians—and aren’t done with us yet.

- Cancer // At Least 1.7 Million Years Old

- Tuberculosis // At Least 70,000 years old

- Dental Caries // At Least 15,000 years old

- Malaria // At Least 5500 years old

- Lyme Disease // At Least 5300 years old

- Leishmaniasis // At Least 4000 years old

Cancer // At Least 1.7 Million Years Old

The true origins of cancer may always be murky, but recent research has shown that it’s likely one of the oldest diseases in the world.

In 2016, a paper in the South African Journal of Science reported the world’s oldest known human malignant tumor on a 1.7-million-year-old toe bone from a hominin unearthed in South Africa’s Swartkrans Cave. Using advanced 3-D imaging, the researchers’ analysis showed it to be osteosarcoma, a kind of cancer found in the cells that form new bone. Another study from the same research team reported the discovery of the earliest case of a benign tumor in a hominin: an osteoid osteoma on the vertebra of a 1.98-million-year-old Australopithecus sediba at the Malapa fossil site in South Africa.

In a more recent case, a 2250-year-old Egyptian mummy named M1 was diagnosed with prostate cancer via a CT scan. He showed signs of lesions in the spine and pelvis that indicated the cancer had metastasized in his bones. Fortunately, numerous options for the treatment of prostate cancer in its various stages is available today.

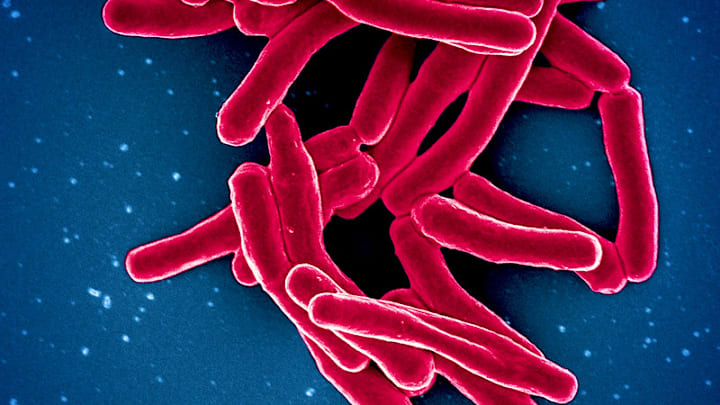

Tuberculosis // At Least 70,000 years old

Tuberculosis, primarily a lung infection, is one of the world’s deadliest known diseases. It’s spread by tiny droplets carried through the air when an infected person speaks, sneezes, or otherwise exhales, and it may be the deadliest bacterium in human history.

Its origins are ancient. Paleomicrobiologists—scientists who study the microbes in prehistoric tissues—suggest that TB was present among Paleolithic humans in Africa 70,000 years ago. As people migrated around the world, the disease tagged along with them. In the 17th and 18th centuries it went by a variety of names, including consumption, white plague, or phthisis (pronounced “THI-suhss”).

By the time the bacterium that causes TB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, was discovered by German physician Robert Koch in 1882, it was killing one out of every seven people in the U.S. and Europe.

Initial symptoms of a TB infection include cough, fever, and fatigue. The disease usually progresses to a latent infection in which people show no symptoms, followed by an active infection in which the person’s immune system can no longer control the spread of the bacterium, and the infected person may cough up blood, feel fatigued, and have no appetite. Active infections are now treated with antibiotics and latent TB can be treated before serious symptoms develop.

Thought it’s curable, tuberculosis still killed 1.3 million people in 2022 and is now the world’s second deadliest infectious disease after COVID-19. It’s also been recognized with a Guinness World Record as the oldest contagious disease. Congratulations?

Dental Caries // At Least 15,000 years old

Dental caries, a.k.a tooth decay, is the most widespread disease in the United States—and humans have been suffering from it for thousands of years.

It was once thought that Paleolithic hunter-gatherers had sidestepped bad teeth thanks to their low-carb lifestyle, and that dental caries first showed up when people started farming grains and other starches. These foods begin breaking down into sugars in the mouth, and bacteria like Streptococcus mutans metabolize the sugars into tooth-decaying acids.

But a 2014 study from London’s Natural History Museum revealed an interesting twist at the site of a hunter-gatherer society in Morocco that lived as many as 15,000 years ago. Skeletal remains at the site showed serious tooth decay—so bad that many of the people would have been chewing food on the roots of their teeth. The likely culprits were the acorns and pine nuts that they frequently ate, which were full of fermented carbohydrates. Lead author Louise Humphrey told NPR that the prevalence of ancient dental caries depended on the foods that were available to forage.

Tooth decay can lead to cavities, pain, and tooth loss, and is preventable with good oral hygiene and dental care. Too bad for this group that the first sort-of toothbrush, the “chew stick,” didn’t come into use for teeth cleaning until about 3000 BCE.

Malaria // At Least 5500 years old

In World War II, U.S. soldiers fighting in the Philippines and New Guinea were leveled by malaria, and many Americans still associate the disease with the war. Extensive public health efforts and other factors contributed to the eradication of malaria from the U.S. by 1951.

But malaria goes a great deal further back in time. In a 2024 study in the journal Nature, researchers looked at genetic material from slivers of ancient human remains from 16 countries and found malaria in specimens that were 5500 years old. The authors believe the disease may be even older than that.

Malaria is caused by a blood parasite in the genus Plasmodium, which is carried by the female Anopheles mosquito. Humans can contract malaria if they’re bitten by one of the infected insects. Initial symptoms are fever, chills and weakness, but if it’s left untreated, malaria can lead to organ failure and death. It’s a leading cause of illness in sub-Saharan Africa, where Anopheles mosquitoes bite humans 98 percent of the time and quickly transmit infections far and wide, and where the majority of the victims are children under 5 years old. The World Health Organization (WHO) recorded 249 million malaria cases and 608,000 fatalities worldwide in 2022.

There are several ways to diagnose and treat malaria depending on a patient’s physical condition and type of malarial symptoms. The WHO approved the first malaria vaccine in 2021.

Lyme Disease // At Least 5300 years old

Lyme disease was first described in 1975, but evidence of it goes way back—to the Copper Age, roughly 5300 years ago.

The bacterium that causes Lyme’s disease, Borrelia burgdorferi, was found by mitochondrial DNA analysis in the bones of Ötzi the Iceman, the oldest known European mummy. Ötzi, named for the Ötztal Alps where he was found in 1991, died in 3300 BCE from a wound caused by an arrowhead lodged in his left shoulder. The injury would have caused his death, “most likely from blood loss, exposure, and shock,” according to a 2013 paper in the journal Inflammopharmacology. We may never know if Ötzi experienced symptoms of Lyme disease from his B. burgdorferi infection, but it’s unlikely that it contributed to his demise.

Lyme disease wasn’t identified for another 5275 years, and only when conditions were just right for it to emerge en masse. In 1975, a group of children in Lyme, Connecticut, developed symptoms that looked like rheumatoid arthritis. Soon more people in nearby towns came down with the same illness [PDF], and in 1981 scientists pointed to Borrelia burgdorferi, a pathogen carried by deer ticks, as the cause.

Why did it emerge so suddenly? According to a 1994 paper, reforestation in the Northeast U.S. beginning in the 1920s supported new habitats for deer. Then came the creation of suburbs, with patches of meadow framed by trees interspersed with woodland—a favorite environment of both deer and humans. The deer brought deer ticks, which carried the bacterium, into more frequent contact with people.

Signs of Lyme disease include fever, chills, muscle aches, and fatigue, progressing into arthritis-like symptoms, heart palpitations, and a red skin rash that looks like a target. If caught early, Lyme disease can be treated with antibiotics.

Leishmaniasis // At Least 4000 years old

Leishmaniasis is another insect-borne disease that’s been with us for millennia. The infection comes from parasites in the genus Leishmania that live inside female sandflies belonging to the genus Phlebotomus. Humans contract Leishmaniasis from the sandflies’ bites, and cases are most common in tropical and subtropical areas around the world.

According to the WHO, up to 1 million cases are diagnosed each year, with the majority being cutaneous Leishmaniasis resulting in skin sores. The visceral and mucocutaneous forms of the disease are rare but more serious. Only a small percentage of those infected ever develops the disease, and there are several treatment options depending on the parasite species and other factors.

A 2006 study in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases examined tissues from 42 ancient Egyptian and Nubian mummies dating from the Middle Kingdom (2050–1650 BCE). Researchers discovered the mitochondrial DNA of Leishmania in four of them, making Leishmaniasis at least 4000 years old, and Egyptian medical writings from 1500 BCE describe a Leishmaniasis-like skin condition called “Nile pimple.” The pathogens in the Leishmania group emerged even earlier, likely during the Mesozoic Era (252 to 66 million years ago).

Discover More Stories About Medical History: