On one end of the frequency spectrum is the, which is used more often than any other English word. On the other end are nonce words: those “coined and used apparently to suit one particular occasion,” according to Britannica. The term comes from for the nonce, a nearly 900-year-old expression meaning “for the particular purpose.”

But it’s a little less simple than that, in part because scholars have different ideas about what qualifies as a nonce word. In their 2005 book Lexicalization and Language Change, for example, linguists Laurel J. Brinton and Elizabeth Closs Traugott stipulate that a nonce word “is formed by applying regular word formation rules.” So you could look at words like otherwise and lengthwise and then apply the suffix -wise to a word it doesn’t usually follow. Or you could create an entirely new word from existing morphemes: The English language has fr- words (e.g. fright, free, frown) and -ink words (e.g. drink, pink, blink), so frink is a viable nonce word. But by Brinton and Traugott’s definition, you couldn’t just toss a random collection of consonants together—say, ssgmrtpwk—and call it a nonce word.

Moreover, not all nonce words remain for the nonce. Some end up getting assimilated into the language at large, and it’s often difficult to pinpoint exactly when a nonce word stops being a nonce word. For linguist Laurie Bauer, it’s “as soon as the speakers using it are aware of using a term which they have heard already: that is to say, virtually immediately.” If 60 different people independently use best-friendable to describe a person they could easily see themselves becoming best friends with, Bauer would still consider it a nonce term—because it’s more about awareness than frequency.

All this to say that the finer criteria for nonce words are debatable, and you could probably make an argument against the nonce-ness of any term in the list below. But they do fit the most general definition of nonce word: a made-up word that served one purpose and never really caught on (not that it was always meant to catch on in the first place).

1. Puzz

Comedian Rich Hall coined the term sniglet to describe “any word that doesn’t appear in the dictionary, but should.” Sniglet itself has been tossed around enough that it may no longer be a nonce word, but plenty of sniglets that Hall made up—he has books full of them—still could.

Puzz, probably a portmanteau of puzzle and fuzz, is “the stuff that collects at the bottom of a jigsaw puzzle box.”

2., 3., 4., and 5. Brillig, Slithy, Tove, and Wabe

Fiction is a breeding ground for nonce words, and no work more so than Lewis Carroll’s poem “Jabberwocky,” which appeared in full in Through the Looking-Glass. It’s rife with nonsense terms, some of which have entered the broader lexicon—like chortle, an apparent portmanteau of chuckle and snort whose meaning reflects the combination of those two actions.

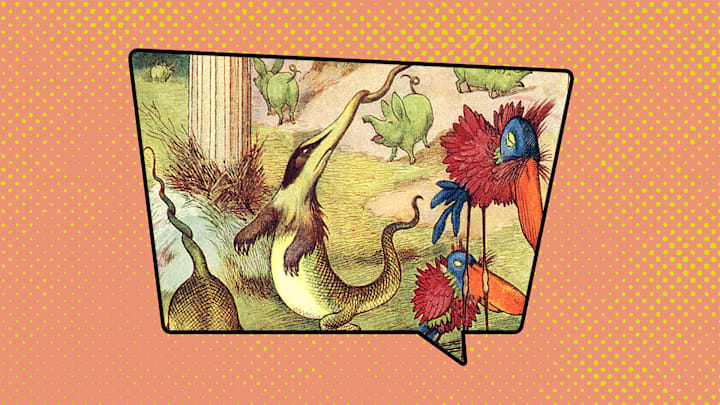

Other Carroll coinages from “Jabberwocky” haven’t been so lucky (yet, at least), including several in its very first lines: “’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves / Did gyre and gimble in the wabe.” Brillig, as Humpty Dumpty tells Alice in Through the Looking-Glass, “means four o’clock in the afternoon—the time when you begin broiling things for dinner.” Slithy means “lithe and slimy,” Humpty explains, and toves are a kind of corkscrew-shaped lizard-badger hybrid that “live on cheese” and nest beneath sundials. A wabe, meanwhile, is the expansive plot of grass surrounding a sundial. (Gimble was technically already a word, though Carroll might not have known that. In any case, he gave it a new sense: “to make holes like a gimlet,” per Humpty.)

Read More Articles About Words:

6. Gostak

One highlight of educator Andrew Ingraham’s 1903 collection of lectures is this seemingly meaningless sentence: The gostak distims the doshes. Ingraham’s point was that it wasn’t meaningless at all.

“We know that the doshes are distimmed by the gostak. We know too that one distimmer of doshes is a gostak. If moreover the doshes are galloons, we know that some galloons are distimmed by the gostak,” he wrote.

In other words, as David Marsh once put it for The Guardian, we can “[derive] meaning from the syntax of a sentence even if it is semantically meaningless.” Any English speaker intuitively understands (even if they can’t articulate it in as many words) that gostak is a noun and the subject of the sentence, distim is a verb—an action being done by the gostak—and doshes is the object, i.e. the receiver of the action.

The gleanings don’t stop there: We also know that distims is a present-tense verb and that gostak is singular (in the same way we know that the deer leaps refers to one deer, while the deer leap refers to multiple deer). Doshes, on the other hand, likely refers to more than one dosh, in the same way that dishes is more than one dish.

From there, we can change the forms and formation of the words in the sentence just like Ingraham did. If more gostaks were distimming, it would take less time to distim all the doshes. Not every dosh is distimmable.

But what exactly is a gostak? It’s what distims the doshes.

7. Wug

Oftentimes, nonce words like gostak are coined for research that examines people’s (usually children’s) linguistic comprehension skills. One especially memorable study is the wug test, which psycholinguist Jean Berko Gleason conducted in the 1950s [PDF].

Gleason wanted to know if young children (between 4 and 7 years old) were already able to apply certain grammar rules to unknown terms. To test their understanding of plurals, she presented them with her illustration of a fictional bird-like creature and told them it was a wug. After seeing an illustration of two of the creatures, the kids were asked to finish the sentence “There are two ___.” Gleason found that the participants, young as they were, knew intuitively that the answer was wugs.

Wug was far from the only nonce word that Gleason created for the study. Among the others were gutch (another bird), lun (a kind of flower), and spow (a verb that describes balancing a steaming pitcher on your head).

8. Cudgellee

For centuries, English speakers have enjoyed slapping the suffix -ee onto the end of various transitive verbs to describe a person to whom that action is done. Not all the terms have stuck as well as employee. Take cudgellee, which American author Thomas Green Fessenden mentioned in his 1805 book Democracy Unveiled; Or, Tyranny Stripped of the Garb of Patriotism: A certain gentlemen “had the honour to be the cudgellee” during a “cudgelling in Congress.” That gentleman also has the honor of being the only cudgellee on record: The Oxford English Dictionary hasn’t unearthed a single other appearance of the word.

9. and 10. Pizmotality and Puppetutes

Musician Vernon Green coined pizmotality in the lyrics of “The Letter,” a 1954 song recorded by his doo-wop group The Medallions: “Let me whisper sweet words of pizmotality / And discuss the puppetutes of love.” Green later defined pizmotality as “words of such secrecy that they could only be spoken to the one you love.”

Puppetutes is another Green original, referring to “a secret paper-doll fantasy figure [thus puppet], who would be my everything and bear my children.” If the phrase puppetutes of love sounds familiar, it’s likely because you’ve heard the Steve Miller Band’s 1973 hit “The Joker,” which contains the phrase pompatus of love. Miller misheard Green’s word and ended up making up his own version, which he never really had a definition for.