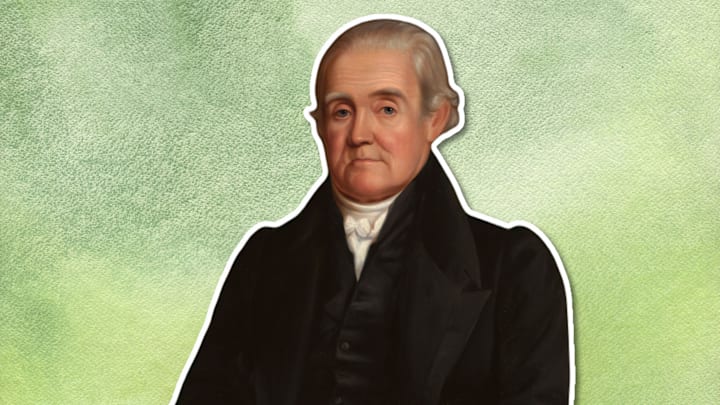

When you think of America’s Founding Fathers, you probably think of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Ben Franklin, and others who played crucial roles in winning the country’s independence and establishing its government. But our language and literature are at least as crucial to our identity as our political infrastructure, and few Americans have shaped those fields to the extent of Noah Webster.

Besides compiling America’s most influential dictionary and Americanizing our English, Webster—who was born in West Hartford, Connecticut, on October 16, 1758—essentially founded the publishing industry, started New York City’s first daily newspaper, and was a pioneer in epidemiology. Here are nine things you should know about Webster and his remarkable career.

1. Noah Webster wrote America’s first bestseller—and it wasn’t a dictionary.

Webster is best remembered for 1828’s An American Dictionary of the English Language, which eventually morphed into the Merriam-Webster family of print and online dictionaries still in use today. But Webster’s most commercially successful work was a 120-page speller first published in 1783, when Webster was only 25 years old. Widely known as the “blue-backed speller” for its distinctive cover, it was the first volume of a collection of textbooks formally titled A Grammatical Institute of the English Language.

Webster’s schoolbook was an immediate success, selling out its first print run in nine months [PDF]. According to the National Museum of Language, it was “the most popular American book of its time” and the first book to roll off U.S. presses in large quantities, with sales eventually approaching 100 million copies. The U.S. Copyright Office calls it “America’s first bestseller.” During its first century in print, Webster’s speller outsold every book in America except the Bible.

2. He helped establish U.S. copyright law.

Webster’s blue-backed speller was more than America’s first publishing success story; it helped establish the laws that allowed publishing to become an industry in the first place.

Webster finished the speller in 1782, after America had won independence from Britain and was no longer subject to British laws. America had no federal copyright law, so to protect his work, Webster traveled from state to state advocating for copyright legislation. His first success came in January 1783 with Connecticut’s “Act for the Encouragement of Literature and Genius,” with several other states passing similar laws over the next few years. May 1790 saw the passing of America’s first Federal Copyright Act, which a 1925-1926 edition of the Yale Law Journal attributed to Webster’s efforts.

3. Webster founded New York City’s first daily newspaper.

From 1792 until 1799, France was engaged in armed conflicts with several European nations and monarchies, including Russia, Portugal, the Ottoman Empire, and, most importantly for American interests, Spain and Great Britain. France hoped to enlist the United States to help undermine Spanish and British interests in the Americas. To that end, the Republic of France’s young government sent a diplomat named Edmond Charles Genêt to America to drum up support for its cause. Genêt took his case directly to the American people, ginning up support for France in high-profile public appearances that often generated fawning media coverage.

Genêt’s maneuvers were not warmly received by the U.S. government. Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton and his Federalists were inclined to side with Great Britain, while President George Washington officially declared America neutral. Washington didn’t want another war with Britain, and he was unnerved by the increasingly violent nature of the French Revolution. (It’s not called “the Reign of Terror” for nothing.)

Understanding the power of the press to shape public sentiment, Washington decided to launch a newspaper that would hopefully erode American support for Genêt. Washington’s administration wanted Noah Webster to establish and edit the paper. (Washington and Webster had been friends since at least 1785, when the retired general and future president invited the young writer to Mount Vernon to discuss Webster’s ideas for America’s nascent government.) Webster launched The American Minerva, named for the Roman goddess of wisdom, on December 9, 1793. The paper went through a series of name changes before becoming the Commercial Advertiser in 1797 and The Sun in 1920. Webster served as the paper’s editor until 1803.

4. He was one of America’s most prolific authors.

Webster’s pair of massively influential dictionaries—1806’s A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language and 1828’s An American Dictionary of the English Language—would be enough to make him a giant of American letters. But his contributions to the country’s lexicography represent only a fraction of Webster’s literary accomplishments. He was such a prolific writer that a 1958 annotated bibliography of his work clocks in at an astonishing 655 pages, cataloging Webster’s textbooks, dictionaries, essays, editorials, letters, published speeches, and more.

5. Webster opposed the Bill of Rights.

Like many Federalists, Webster was convinced that, as a democratically governed country, America had no need for a Bill of Rights. He believed attaching inalienable rights to a constitution was “absurd” because such documents would necessarily evolve over time. “The present generation have indeed a right to declare what they deem a privilege,” he wrote in a 1788 essay (emphasis his), “but they have no right to say what the next generation shall deem a privilege.”

Webster also worried that some of the rights established in the bill constituted a slippery slope. Ironically, the journalist and future newspaper editor was especially concerned about the bill’s guarantee of freedom of the press. He feared the power of what he called the “extreme virulence of partisan malevolence” to shape public opinion, “corrupt[ing] the people by rendering them insensible to the value of truth and reputation.” Webster laid out his case against a sweeping “liberty of the Press” in a 1787 editorial in the New York Daily Advertiser, arguing that the proposed amendment would be exploited by unscrupulous publishers. “Rather than hazard such an abuse of privilege,” Webster asked, “is it not better to leave the right altogether with your rulers and your posterity?”

6. He viewed English as a living, ever-evolving language.

Webster maintained that, since Americans would never have personal experience with historically English institutions and practices (he used falconry and the feudal system as examples), words and expressions derived from those hallmarks of English life had no place in American language. He thought Americans needed a specifically American dictionary that would help standardize and codify the country’s rapidly evolving vocabulary—one that acknowledged its novel system of government and civic life, allowed for the expression of distinctly American ideas, and made room for loanwords from Native American cultures. Webster believed American English would eventually evolve so dramatically that it would seem like a foreign language to speakers of British English.

7. He censored the Bible.

Webster was raised in a deeply religious household, and sometime around 1808, he became what we would now call a born-again Christian. Over the years, he developed an aversion to the King James Bible, which he considered archaic, grammatically subpar, and, well, dirty. In 1832, he produced his own edition of the KJV, published in 1833 as The Holy Bible, Containing the Old and New Testaments, in the Common Version, with Amendments of the Language. Webster’s Bible used updated and simplified language, so of a surety became surely and kine became cows. But its most remarkable changes involved censoring passages that, in Webster’s words, “cannot be repeated without a blush.” After Webster’s edits, some of the KJV’s instances of fornication became vague references to lewdness. He also replaced one use of the word stones with male organs, and changed whore to lewd woman throughout.

8. Webster’s ideas about climate change have not aged well.

Thomas Jefferson was writing about climate change as early as 1787, noting that “heats and colds [had] become much more moderate,” “snows [were] less frequent and less deep,” and rivers that had routinely frozen over in winter months were no longer doing so. Jefferson worried about how such trends would affect crops, and he wondered if human activity was contributing to the changes he and others were observing. According to Smithsonian Magazine, the idea that mankind was changing the climate wasn’t controversial in Jefferson’s time.

Webster took issue with the suggestion, though, and set out to refute Jefferson’s theory. In two speeches—one in 1799 and one in 1810—Webster ridiculed Jefferson’s concerns, insisting the famed statesman was relying on “the observations of elderly and middle-aged people” rather than empirical data. He allowed that deforestation might contribute to changes in local weather conditions, but rejected the idea that humans were affecting their environment on a continental, let alone global, scale. Webster essentially shut down the climate debate until the late 1950s, when scientists began to monitor CO2 levels and their wide-ranging effects.

9. He was one of America’s first epidemiologists.

The yellow fever outbreaks of the 1790s are widely regarded as America’s first epidemic. Philadelphia was the site of the first outbreak, with about 10 percent of the city’s population succumbing to the disease in the summer and fall of 1793. Yellow fever struck New York in the summer of 1795. “The whole city, is in a violent state of alarm on account of the fever,” wrote one doctor in September. “It is the subject of every conversation, at every hour, and in every company.”

Since no one knew how the disease was communicated, no one knew how to curb its spread. Webster understood the importance of collecting information about the illness, so in the fall of 1795, he put out a call in his newspaper asking physicians in cities that had been heavily affected to send him whatever they had learned so far. The following year, he compiled the responses in A Collection of Papers on the Subject of the Bilious Fevers, Prevalent in the United States for a Few Years Past. In 1798, when the disease struck again, Webster responded with the two-volume, 700-page A Brief History of Epidemic and Pestilential Diseases: with the Principal Phenomena of the Physical World, Which Precede Them and Accompany Them, and Observations Deduced from the Facts Stated. (One can only hope he later reconsidered his definition of the word brief.)

According to biographer Joshua Kendall, Webster helped advance the relatively new science of public health and set a precedent for future epidemic and pandemic responses, including collecting and sharing information and coordinating the efforts of health care workers. Curtis L. Patton, Ph.D., professor emeritus of epidemiology at Yale, has called him the “father of epidemiology—indeed, father of all public health in America.”