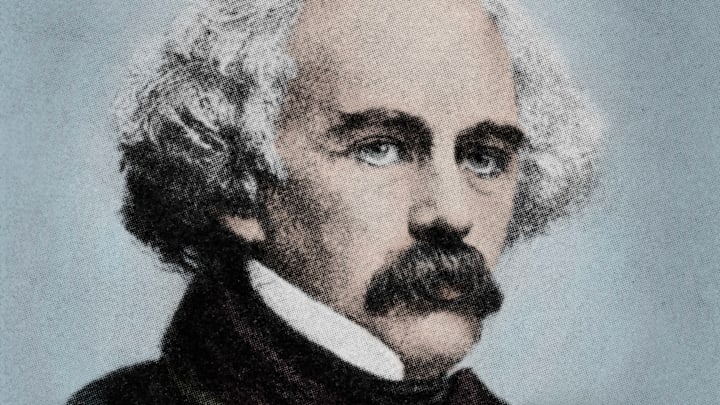

American novelist and short story writer Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864) drew inspiration from colonial New England for his best-known works, The Scarlet Letter (1850) and The House of the Seven Gables (1851). Both critiqued morality and human nature, subjects that Hawthorne’s Transcendentalist friends Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau were also exploring in their philosophy. Here are 12 facts about the man once called “handsomer than Lord Byron.”

1. Nathaniel Hawthorne was related to a key prosecutor in the Salem Witch Trials …

Hawthorne, born on July 4, 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, was the great-grandson of Judge John Hathorne, one of the most fervent prosecutors in the town’s witchcraft trials. Hathorne played a central role in the crusade to execute 20 people suspected of witchcraft in 1692. That wasn't Hawthorne's only connection to the Salem Witch Trials; an accuser named Sarah Phelps was the great niece of Hawthorne’s maternal great-great grandfather.

The inspiration for Hawthorne’s second novel, The House of the Seven Gables, stems from this family history. In the book, the fictional Pyncheon family lives in a mansion based on the real-life Turner-Ingersoll mansion in Salem, which Hawthorne visited after his second cousin, Susanna Ingersoll, inherited it.

2. … And to some of the accused witches.

Hawthorne’s great uncles married two granddaughters of Mary and Philip English, a prosperous couple who were both accused of witchcraft but not convicted.

Hawthorne’s cousin from a different lineage married the great-great-great grandson of John Proctor, the first man to be accused of witchcraft; Proctor was executed on August 19, 1692. Another acquitted “witch,” Sarah Wilson, was married to a descendant of Hawthorne’s maternal grandmother.

3. Hawthorne added the W to his last name.

Hawthorne added the extra letter to his surname, perhaps to distinguish himself from some of his ancestors—including Judge Hathorne and his great-great-grandfather, William Hathorne, a magistrate who sentenced a Quaker woman to a brutal public flogging. No one knows exactly why Hawthorne did it, though.

4. He tried to destroy his first novel.

Hawthorne anonymously self-published his first novel, Fanshawe, a Gothic romance, in 1828 while he was a student at Bowdoin College in Maine. He regretted the decision not long after (perhaps after it received poor reviews) and tried to destroy all copies. Reportedly, his wife didn’t find out the book existed until after he had died.

5. Hawthorne was a college classmate of a future U.S. president.

Hawthorne met Franklin Pierce while both were students at Bowdoin College in the 1820s, and they remained lifelong friends. When Pierce received the Democratic nomination for president in 1852, Hawthorne wrote his campaign biography. By then, Hawthorne had achieved fame and accolades for The Scarlet Letter and The House of Seven Gables, and he was scorned for writing Pierce’s biography. The author claimed that his job for the anti-abolitionist candidate had cost him “hundreds of friends” in the North.

When Pierce was elected president in 1853, he repaid the favor by giving Hawthorne a high-paying gig as the U.S. consul in Liverpool, UK, a sinecure that made it easier for Hawthorne to spend time writing. He and his family lived in England from 1853 to 1857.

6. He saved money for his marriage by living in a commune.

Hawthorne met Sophia Peabody in 1838 while supposedly courting her sister, Elizabeth. The Peabodys were a connected and intellectual Salem family; Elizabeth joined the Transcendentalist circle (it was she who thought Hawthorne was handsomer than Lord Byron), while another sister, Mary, was an education activist and married fellow reformer Horace Mann. Sophia was closing in on 30 years old and had told her sister that she didn’t want a husband. She and Hawthorne hit it off, however, and were engaged in 1839.

Hawthorne, then a struggling writer, was nearly broke and moved to the Transcendentalist community Brook Farm in April 1841, thinking he could save money. The 175-acre farm outside Boston was an experimental utopian society and Hawthorne was considered one of its founding members. But he hated commune life and farming, particularly his job shoveling a hill of manure nicknamed “the gold mine,” and left after six months.

7. Hawthorne and his wife etched poems into the windows of their first home.

Hawthorne and Sophia Peabody married on July 9, 1842, at Elizabeth Peabody’s Transcendentalist bookstore in Boston, then moved into The Old Manse in Concord, Massachusetts, a two-and-a-half-story clapboard house built by Ralph Waldo Emerson’s grandfather. Henry David Thoreau planted an heirloom vegetable garden for the couple and Emerson loaned them money the first few years of their marriage.

The pair lived at the Old Manse for three years and etched poems for each other into the windowpanes, which are still visible today. Sophia carved her name into the glass with her engagement ring.

8. He saw a ghost at the Boston Athenaeum.

While living in Boston, Hawthorne often visited the reading room at the Boston Athenaeum, an elegant subscription library. One day in April 1842, Hawthorne noticed the elderly Reverend Thaddeus Mason Harris at his usual spot near the fireplace, reading The Boston Post. Later that night, he was surprised to learn from a friend that Harris had died.

In a story he told later, Hawthorne said he questioned whether he had really seen Harris earlier that same day, but that upon entering the reading room the following afternoon, Harris was once again seated in the same chair and reading the same paper (Hawthorne quipped that Harris could have been reading his own obituary). Hawthorne claimed to have seen Harris during several subsequent visits.

9. Herman Melville dedicated Moby-Dick to Hawthorne.

Shortly after The Scarlet Letter’s publication, Hawthorne lived in Lenox in the scenic Berkshires of western Massachusetts. He met and befriended Herman Melville, who resided with his family in nearby Pittsfield. Melville, then a bestselling author of adventure novels, was nearly finished writing Moby-Dick, a much darker and more complex tale, but he blew his book deadline by a year to rewrite the manuscript according to Hawthorne’s feedback. Melville dedicated the novel to Hawthorne and wrote a gushing letter of thanks to his mentor (among many other love letters).

10. Franklin Pierce discovered Hawthorne’s body.

Hawthorne’s health had taken a turn for the worse by 1860. He moved his family back to the United States—after their life in England and an extended vacation to Italy—and finished his final novel, The Marble Faun.

In spring 1864, Hawthorne took a trip to the White Mountains with Pierce, who had a house in Concord, New Hampshire, in the hopes of regaining some health. On May 18, they visited Dixville Notch and stopped at the Pemigewasset Hotel for the night. There, Pierce checked on his friend in the middle of the night and found that he had passed away. Hawthorne was 59.

11. Louisa May Alcott’s father was one of Hawthorne’s pallbearers.

The Alcott family owned a house in Concord, Massachusetts, which they called “The Hillside,” from 1845 to 1852 (Louisa May Alcott used it as the setting for Little Women). Hawthorne then owned the house from 1852 to 1864 and called it “The Wayside,” the name it currently bears.

After Hawthorne died in New Hampshire, his body was sent to Concord, Massachusetts, for burial. Bronson Alcott, Louisa’s father and a prominent Transcendentalist, was among the pallbearers, along with Emerson, poets Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and John Greenleaf Whittier, and naturalist Louis Agassiz. Writers Oliver Wendell Holmes and James T. Fields are also mentioned as pallbearers. Pierce, hated by Hawthorne’s contemporaries, was not a pallbearer but sat with the Hawthorne family.

12. Hawthorne’s younger daughter was nominated for sainthood.

Hawthorne’s third child, Rose, married George Parsons Lathrop, an editor at Atlantic Monthly. Their marriage was difficult; George was a heavy drinker and their only child, Francis, died at 5 of diphtheria. The couple converted to Catholicism in 1891, and with permission from the church, Rose left George in 1895 to focus on charitable works.

Rose moved to the slums of New York City and founded a health clinic to aid (in her words) the “cancerous poor.” In 1900, she took her vows and the name Mother Mary Alphonsa and founded a religious order called the Servants of Relief for Incurable Cancer. She died in 1926, having spent the second half of her life serving impoverished cancer patients.

Rose Hawthorne’s order is now known as the Dominican Order of Hawthorne and continues her mission. In 2003, Cardinal Edward Egan, then the archbishop of New York, put Mother Mary Alphonsa on the path for sainthood.